Mycobacterium xenopi is a slow-growing environmental nontuberculous mycobacterium whose complete genome has recently been characterized, providing valuable insights into its virulence mechanisms and resistance pathways [1]. Traditionally considered an opportunistic pathogen, its role as an emerging pathogen in clinical practice has been debated since the late 20th century [2]. Most infections described to date occur in immunocompromised patients or in those with underlying structural lung disease [3]. However, uncommon extrapulmonary involvement has also been reported, including osteoarticular infections [4]. From a therapeutic standpoint, the management of M. xenopi infection remains a clinical challenge, with treatment models largely based on international guidelines [5].

Pleural involvement in immunocompetent patients is exceptionally rare, with only a few cases described. We report an unusual case of pleural infection by M. xenopi in an immunocompetent young woman, with significant diagnostic and therapeutic implications.

A 31-year-old Caucasian woman, living in an urban setting with her mother and grandmother, independent in activities of daily living, and employed as a shop assistant, was admitted to our department. She had no history of toxic habits or animal contact. Her family history included colorectal cancer in her maternal grandfather. She reported no drug allergies, cardiovascular risk factors, or previous medical or surgical history of relevance. Her only medication was mirtazapine 15mg nightly, without a prior formal diagnosis of anxiety-depressive disorder.

She presented with marked asthenia, several kilograms of unintentional weight loss in the previous year, abdominal distension, nausea, and constipation. She denied pleuritic chest pain, dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, fever, chills, cough, or sputum production. On examination, she had a BMI of 17kg/m2, temperature 35.5°C, blood pressure 88/67mmHg, and normal cardiac auscultation. Pulmonary examination revealed decreased breath sounds in the left lower field. The abdomen was soft and non-tender, and the rest of the physical exam was unremarkable.

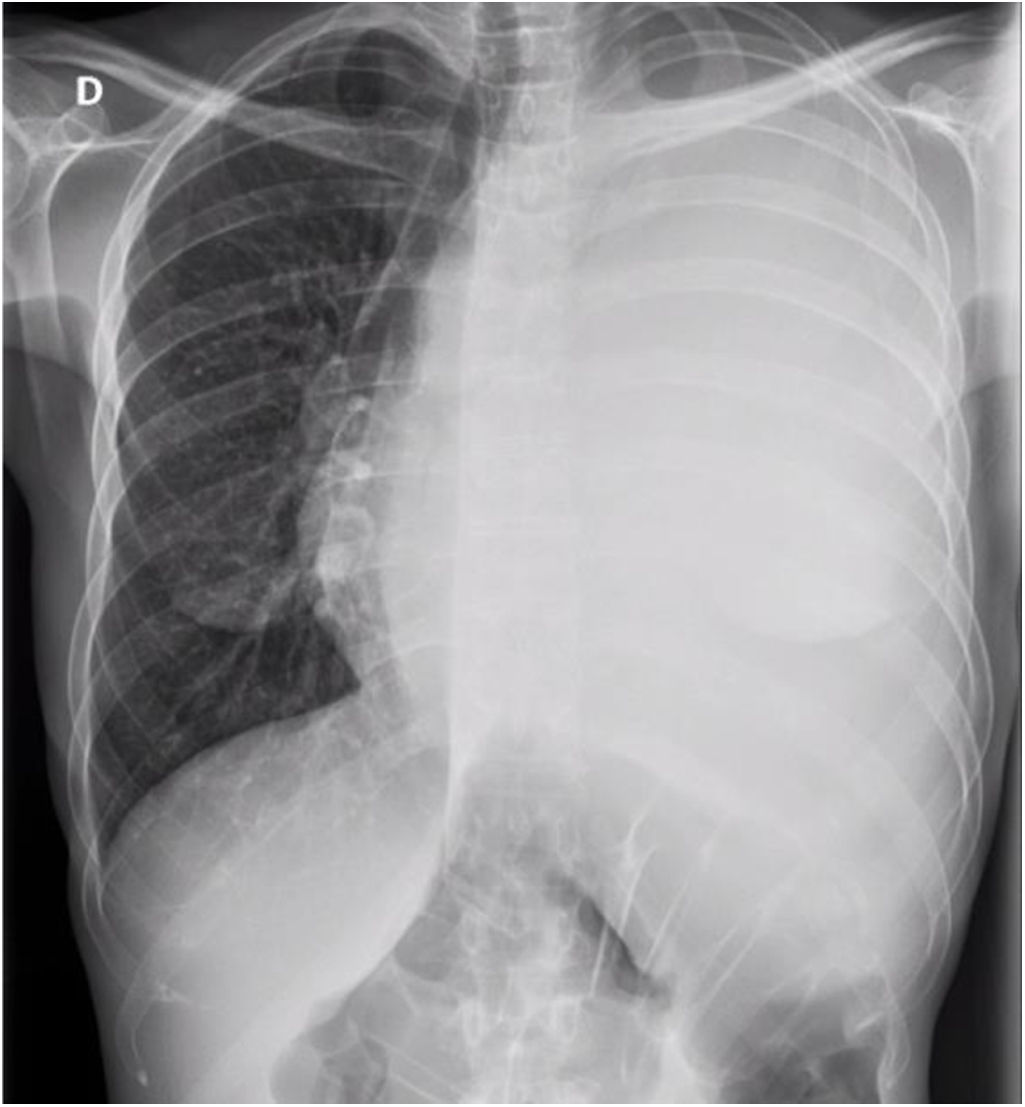

Initial laboratory tests showed normocytic anemia (Hb 11.3g/dL), leukocytes 3820/μL (87% neutrophils), and platelets 226,000/μL, with normal renal and hepatic function. Chest X-ray at admission demonstrated complete opacification of the left hemithorax with contralateral mediastinal shift (Fig. 1).

During hospitalization, further evaluation of her constitutional syndrome included fecal occult blood testing (negative), gastroscopy and colonoscopy (both normal), abdominal ultrasound (normal), and fecal calprotectin (normal).

Thoracic CT revealed massive left pleural effusion with complete lung atelectasis, without parenchymal lesions, lymphadenopathy, or pleural thickening. Diagnostic thoracentesis revealed a clear yellow exudate, with the following biochemical profile: pH 7.1, proteins 42g/L, glucose<2mg/dL, LDH 1164U/L, albumin 27.7g/L, and ADA 72U/L. Cytology showed scarce reactive mesothelial cells and lymphocytes. Bacterial cultures of pleural fluid, acid-fast bacilli smear, and PCR for M. tuberculosis were negative.

Given suspicion of an infectious etiology and absence of microbiological isolation, medical thoracoscopy was performed, revealing whitish pseudomembranes on the visceral pleura and shiny nodular implants on the parietal pleura. Microbiological studies of pleural fluid obtained during the procedure remained negative. However, pleural biopsy demonstrated granulomatous inflammation with acid-fast bacilli on Ziehl–Neelsen staining, prompting initiation of standard antituberculous therapy while awaiting mycobacterial cultures.

The patient developed a complete left pneumothorax following thoracoscopy, complicated by persistent air leak despite chest tube drainage with suction for one month, ultimately requiring surgical management consisting of left upper lobectomy with bullectomy and talc pleurodesis. Histopathology of the resected lobe confirmed findings consistent with the prior thoracoscopic biopsy.

Six weeks after thoracoscopy, while still on antituberculous therapy, M. xenopi was isolated from the pleural biopsy culture. Given the absence of apparent immunosuppression and the exceptional nature of pleural infection by M. xenopi in such patients, an extensive evaluation was conducted. Serologies for HIV, HBV, HCV, and syphilis were negative. Serum immunoglobulins (IgA 1.49g/L, IgM 1.31g/L, IgG 8.66g/L), complement studies, rheumatoid factor, and lymphocyte subsets were within normal limits. Autoimmune testing (ANA, ANCA, anti-smooth muscle, antiphospholipid, anti-liver-kidney microsomal, antimitochondrial antibodies) was negative.

Immunosuppression was ultimately excluded, and a final diagnosis of pleural infection due to M. xenopi in an immunocompetent patient was established. Therapy was switched to clarithromycin 500mg/12h, rifampicin/isoniazid 600/300mg daily, and ethambutol 800mg daily [5]. She was discharged home.

Outpatient follow-up in Pulmonology every 3 months was maintained for 18 months, corresponding to the duration of treatment. The patient showed good adherence and tolerance, with clinical improvement and weight gain, remaining free of respiratory symptoms. At 3 months post-treatment completion, chest CT demonstrated resolution of pleural disease, and sputum cultures for mycobacteria were negative.

M. xenopi is a slow-growing environmental and emerging nontuberculous mycobacterium (NTM). Although most frequently associated with chronic cavitary pulmonary disease, M. xenopi has also been implicated in extrapulmonary infections, including osteoarticular infections [4]. These observations reinforce its role as an emerging pathogen in diverse clinical contexts [2]. Pleural infection due to M. xenopi in immunocompetent patients is extremely rare, with very limited representation in the literature.

In our case, the absence of respiratory symptoms, combined with a lymphocytic exudative pleural effusion with elevated ADA, initially suggested tuberculous pleuritis, the most common diagnosis in this setting. However, negative smear microscopy, PCR for M. tuberculosis, and absence of growth on initial cultures complicated this diagnostic pathway. Malignant pleuritis was also considered, given the massive effusion and the patient's young age, but repeated cytology was negative and imaging showed no evidence of malignancy. Other nontuberculous mycobacteria, including Mycobacterium kansasii and Mycobacterium avium complex, should also be considered in granulomatous pleuritis, necessitating thorough microbiological and histopathological evaluation to ensure accurate diagnosis. In this context, medical thoracoscopy with pleural biopsy was decisive for establishing the final diagnosis.

The delayed microbiological identification of M. xenopi is common, given its slow replication and specific culture requirements. This highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion and considering early invasive techniques in cases of unexplained pleural effusion. This case highlights the importance of considering M. xenopi and other NTM in the differential diagnosis of granulomatous pleuritis, even among young, immunocompetent individuals.

Informed consentThe authors declare that written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the case and the associated images.

Artificial intelligence statementThe authors declare that no generative artificial intelligence was used in the preparation of this manuscript.

FundingThe authors declare that they have not received any funding for the preparation of this work.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.