In recent years, the profile of immunosuppressed patients at risk of developing invasive fungal infections (IFI) has undergone a silent yet profound transformation. In addition to the traditionally recognized high-risk groups, including patients with prolonged neutropenia, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, or solid organ transplantation, a number of new vulnerable populations have recently been identified. These include patients with severe viral respiratory diseases [1], chronic comorbidities such as COPD or cirrhosis, patients treated with biologics or targeted immunomodulatory therapies [2], and those with high or prolonged corticosteroid use [3]. Indeed, the use of corticosteroids across diverse patient populations has likely become the single most important risk cofactor for developing mycosis. Risk is dynamic, and this is often underestimated outside of hematology.

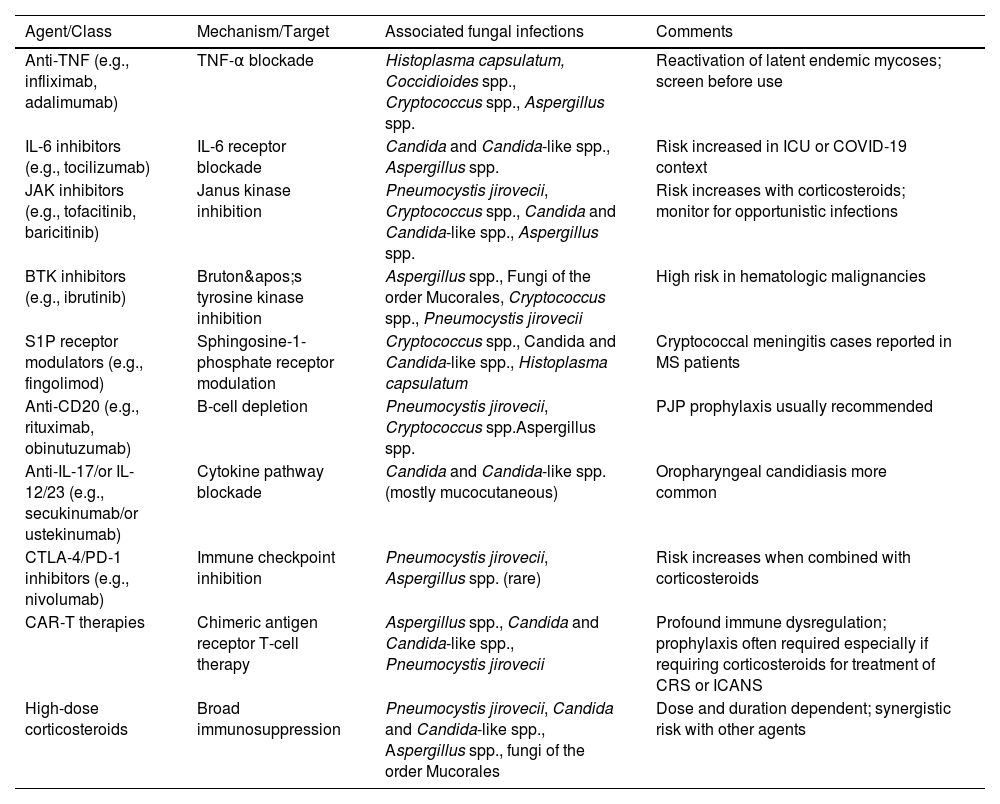

IFI affect distinct patient populations based on the nature of their immunosuppression. Individuals with T-cell deficiencies are particularly vulnerable to Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus spp., Cryptococcus spp., and Histoplasma capsulatum. In patients with neutropenia, the risk increases for infections caused by Aspergillus spp., Candida species (including non-albicans strains), Fusarium spp., and fungi of the order Mucorales [4]. Pharmacologic immunosuppression, including the use of corticosteroids and biologic agents, presents a variable risk profile depending on the immunologic pathway targeted (Table 1). For example, TNF-alpha inhibitors are primarily associated with a heightened susceptibility to endemic fungi, whereas IL-17 inhibitors are more closely linked to mucocutaneous candidiasis. Geographic exposure also remains a critical determinant of risk, with pathogens such as H. capsulatum, Coccidioides spp., and Talaromyces marneffei being endemic to specific regions and posing a threat to both residents and travelers in those areas.

Immunomodulatory agents and risk of fungal infections.

| Agent/Class | Mechanism/Target | Associated fungal infections | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-TNF (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab) | TNF-α blockade | Histoplasma capsulatum, Coccidioides spp., Cryptococcus spp., Aspergillus spp. | Reactivation of latent endemic mycoses; screen before use |

| IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab) | IL-6 receptor blockade | Candida and Candida-like spp., Aspergillus spp. | Risk increased in ICU or COVID-19 context |

| JAK inhibitors (e.g., tofacitinib, baricitinib) | Janus kinase inhibition | Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus spp., Candida and Candida-like spp., Aspergillus spp. | Risk increases with corticosteroids; monitor for opportunistic infections |

| BTK inhibitors (e.g., ibrutinib) | Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibition | Aspergillus spp., Fungi of the order Mucorales, Cryptococcus spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii | High risk in hematologic malignancies |

| S1P receptor modulators (e.g., fingolimod) | Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulation | Cryptococcus spp., Candida and Candida-like spp., Histoplasma capsulatum | Cryptococcal meningitis cases reported in MS patients |

| Anti-CD20 (e.g., rituximab, obinutuzumab) | B-cell depletion | Pneumocystis jirovecii, Cryptococcus spp.Aspergillus spp. | PJP prophylaxis usually recommended |

| Anti-IL-17/or IL-12/23 (e.g., secukinumab/or ustekinumab) | Cytokine pathway blockade | Candida and Candida-like spp. (mostly mucocutaneous) | Oropharyngeal candidiasis more common |

| CTLA-4/PD-1 inhibitors (e.g., nivolumab) | Immune checkpoint inhibition | Pneumocystis jirovecii, Aspergillus spp. (rare) | Risk increases when combined with corticosteroids |

| CAR-T therapies | Chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy | Aspergillus spp., Candida and Candida-like spp., Pneumocystis jirovecii | Profound immune dysregulation; prophylaxis often required especially if requiring corticosteroids for treatment of CRS or ICANS |

| High-dose corticosteroids | Broad immunosuppression | Pneumocystis jirovecii, Candida and Candida-like spp., Aspergillus spp., fungi of the order Mucorales | Dose and duration dependent; synergistic risk with other agents |

Legend: TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; IL, Interleukin; JAK, Janus Kinase; BTK, Bruton's Tyrosine Kinase; S1P, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate; CD20, Cluster of Differentiation 20; CTLA-4, Cytotoxic T-Lymphocyte Antigen 4; PD-1, Programmed Cell Death Protein 1; CAR-T, Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cell Therapy.

The risk of IFI in these groups is real, albeit heterogeneous. However, diagnostic systems, therapeutic recommendations, and—most critically—scientific evidence have not adapted to this evolving clinical context [5]. Clinical diagnosis must be proactive, leveraging molecular tools and biomarkers validated beyond the hematologic populations [6]. The diagnosis of IFI in non-hematological immunosuppressed patients remains particularly challenging. Clinical manifestations are frequently nonspecific, imaging findings are often inconclusive, and the performance of fungal biomarkers such as galactomannan and β-d-glucan is suboptimal and/or insufficiently validated in these settings. Access to invasive diagnostic procedures—including bronchoscopy, bronchoalveolar lavage, or tissue biopsy—is commonly limited due to clinical instability and/or lack of resources, especially in non-specialized centers. As a result, early diagnosis—a fundamental determinant of survival—often depends solely on clinical suspicion and expert judgment, within an environment of persistent diagnostic uncertainty. Moreover, access to diagnostic methods is limited and unequal [7]. Furthermore, in patients with structural lung disease or post lung transplantation, distinguishing between colonization and true infection of the respiratory tract remains a significant diagnostic dilemma, as fungal presence is common but frequently of uncertain clinical relevance.

Therapeutic options also remain limited. First-line antifungal agents such as voriconazole, posaconazole, isavuconazole, and echinocandins continue to be the cornerstone of treatment but pose well-recognized challenges, including drug–drug interactions, hepatotoxicity, and the need for therapeutic drug monitoring. New antifungal compounds with novel mechanisms of action—such as olorofim (an orotomide), ibrexafungerp (a triterpenoid), fosmanogepix (a Gwt1 inhibitor)— and new azoles such as openoconazole and oteseconazole are currently in advanced stages of clinical development [8]. These agents offer promise against resistant or uncommon pathogens; however, their clinical evaluation remains largely restricted to hematologic populations and narrowly defined clinical trial settings.

Among these, olorofim has demonstrated clinical activity in patients with limited treatment options, including cases of aspergillosis, lomentosporiosis, and fusariosis. A phase 2b trial reported clinical response rates, often defined as a composite of clinical, radiological, and mycological resolution [9], of up to 50% at day 42, with an acceptable safety profile. Nevertheless, these findings originate from open-label, uncontrolled studies involving highly selected patients. Non-hematological immunosuppressed populations are less well represented in the development of next-generation antifungal therapies.

At the same time, the incidence of infections caused by rare or difficult-to-treat filamentous fungi—such as Scedosporium apiospermum, Lomentospora prolificans, Rasamsonia argillacea, and Fusarium spp.—continues to increase, particularly among lung transplant recipients and individuals with complex immunosuppressive backgrounds [10]. These infections are often associated with poor prognoses and a lack of high-quality evidence to guide treatment.

The current landscape is no longer defined by the archetypal “high-risk patient.” Instead, it reflects a growing mosaic of immunosuppressive conditions in which fungal risk is dynamic, variable, and not easily categorized. Existing clinical guidelines, although they now include many different types of clinical settings, often offer limited support. Most are based on studies with restrictive inclusion criteria, which do not reflect the complexity and heterogeneity encountered in routine clinical practice.

Addressing this challenge requires several key actions. First, the evolving nature of IFI risk must be acknowledged. These infections are no longer confined to hematology patients. Multicenter cohorts that encompass a wide range of immunosuppressive profiles are needed, alongside diagnostic criteria adapted to varying degrees of immunosuppression and pragmatic clinical trials with broader eligibility. In parallel, clinician awareness must be improved across specialties such as rheumatology, pulmonology, and gastroenterology, where the use of immunosuppressive agents has risen substantially, yet suspicion of IFI remains disproportionately low. Second, the diagnostic toolkit must be expanded and refined. Accessible, rapid, and validated diagnostic methods are essential—particularly molecular techniques, non-invasive biomarkers validated in non-neutropenic patients, and integrated clinical–radiological algorithms capable of guiding early decision-making. Finally, a paradigm shift is required in the conceptualization of immunosuppression and infectious risk. Traditional compartmentalization by specialty—hematology, transplantation, rheumatology—no longer aligns with clinical reality, and as happened with other diseases, such as infectious endocarditis, multidisciplinary mycology teams are needed. A more transversal, risk-based approach is needed, focused on the degree, duration, and clinical context of immune dysfunction rather than on categorical diagnoses.

In summary, an increasing number of patients face a real risk of developing IFI. However, clinical decision-making continues to rely on imprecise criteria, uncertain diagnostics, and evidence extrapolated from limited populations. No trial. No error. Just uncertainty. But within this uncertainty lies a clear opportunity: to generate more inclusive, pragmatic, and clinically relevant evidence—evidence capable of supporting those who must make high-stakes decisions, daily, with no safety net.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.