Benralizumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets the alpha chain of the interleukin-5 receptor (IL-5Rα) on eosinophil membranes, inducing their elimination through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. It has demonstrated efficacy in reducing exacerbations and the need for oral corticosteroids (OCS) in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma [1]. Recent studies suggest that a reduction in inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) doses may be feasible in patients treated with benralizumab who achieve stable disease control [2,3], although this approach remains controversial and is not explicitly specified in current guidelines. The primary objective of this study was to assess the potential for ICS dose reduction in adult patients treated with benralizumab according to indication guidelines, for a minimum of three years. Additionally, we evaluated the progression of respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function in patients with severe asthma on high-dose ICS, defined as 1001–2000μg of beclometasone dipropionate or its equivalent according to the Spanish Asthma Management Guidelines (GEMA) 5.5 criteria [4].

A single-centre, retrospective, longitudinal study was conducted. Data were collected from adult patients with severe uncontrolled asthma at the fifth Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention (GINA) [6] therapeutic step when benralizumab treatment was initiated, and who completed at least three years of treatment, during which they were monitored. This period spanned from January 2020 to December 2023. The exclusion criteria involved the unavailability of study variables in the electronic medical record; however, no patients were excluded. The study protocol was approved by our center's Research Ethics Committee (PI-6093). Demographic variables (gender, age), patient characteristics (smoking status, comorbidities), and spirometric parameters were collected, along with the Asthma Control Test (ACT) scores, the number of severe exacerbations, OCS doses, and the possibility of ICS dose reduction.

Non-biological therapies (LAMA, leukotriene receptor antagonists, OCS and ICS) reduction was conducted at the discretion of the prescribing clinician, given the retrospective nature of the study rather than a controlled clinical trial. Although a strict step-down protocol was not implemented, certain general principles were typically followed. The pharmacological combinations used in our study are shown in “Supplementary material.” In patients receiving biological therapy who no longer experienced exacerbations requiring OCS and showed clinical improvement—assessed using the ACT—without decline, or with improvement in lung function, the first step usually involved discontinuation of LAMA. If symptom control was maintained or further improved, and lung function remained stable without exacerbations requiring OCS, the next step was a reduction in ICS dosage to a medium maintenance level. If any deterioration in clinical status, lung function, or an increase in exacerbations was observed following ICS dose reduction, the step-down was considered unsuccessful. In our cohort, clinicians generally maintained LAMA therapy in patients with persistent airway obstruction, significant sputum production, or a history of smoking. In such cases, if clinical and functional parameters remained stable over time, ICS was often reduced to a medium dose.

Data were extracted from health records. Statistical analysis was performed using R Core Team 2024 version 4.3.3. Categorical variables were expressed as frequency and percentage; continuous normal variables as mean and standard deviation; and non-normal variables as median and interquartile range. Group comparisons were conducted using the Chi-square test for categorical variables, the Student's t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and the Mann–Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. The statistical significance threshold was set at p<0.05 for all comparisons.

A total of 25 adult patients from our severe asthma unit undergoing treatment with benralizumab were included in the study. All of them had uncontrolled severe eosinophilic asthma despite ICS and LABA high-dose: 19 patients (76%) had experienced≥1 severe exacerbation in the previous 12 months requiring one or more courses of oral corticosteroids and 6 patients (24%) were on maintenance OCS therapy for at least 6 months prior to starting benralizumab. All of them initiated benralizumab treatment in accordance with clinical practice prior to the latest Therapeutic Positioning Report (IPT) update (2019).

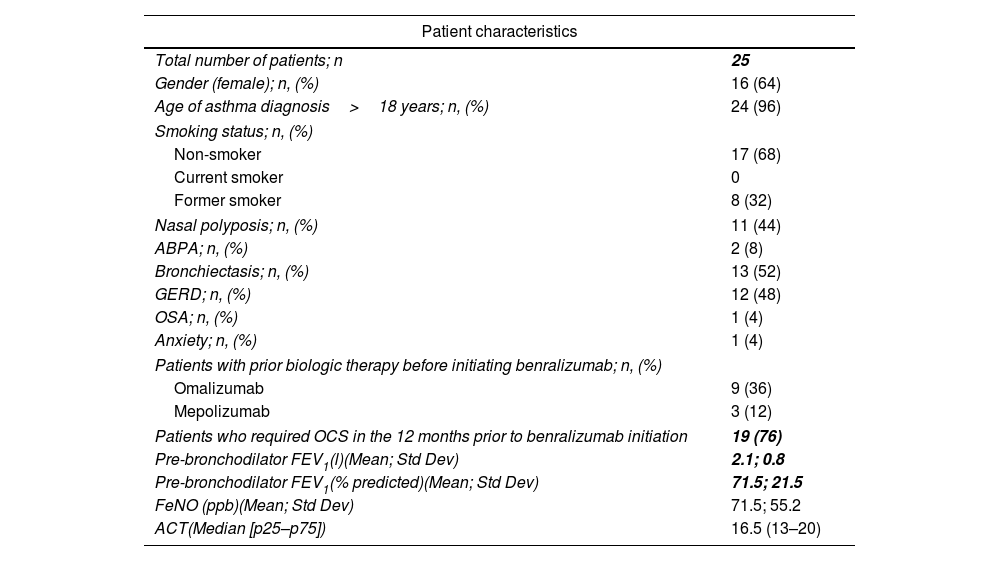

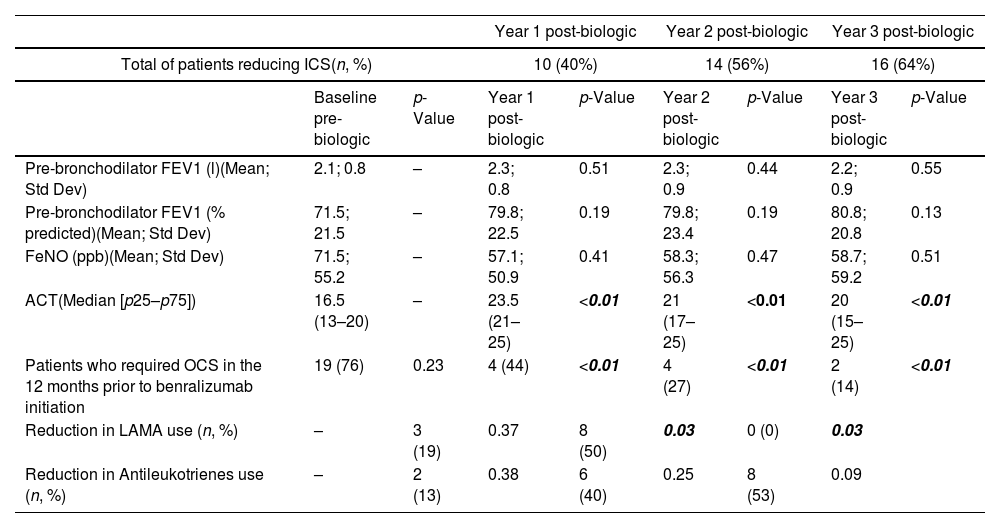

64% of the total patient cohort were women a mean age of 62 years (range: 30–81). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. After one year of benralizumab treatment, ICS doses were reduced to medium doses (501–1000μg of beclometasone dipropionate or its equivalent) in 40% (n=10) of the total patients. The use of LAMA was reduced 19% (Table 2). Two years after initiating benralizumab treatment, 56% (n=14) of patients had reduced ICS doses to medium levels. Likewise, the use of LAMA was reduced to 50% (p=0.03), and this reduction was maintained in the third year of the study. Similarly, after two years, there was a reduction of up to 40% in the use of antileukotrienes (Table 2).

Baseline characteristics of patients with severe asthma initiating benralizumab.

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients; n | 25 |

| Gender (female); n, (%) | 16 (64) |

| Age of asthma diagnosis>18 years; n, (%) | 24 (96) |

| Smoking status; n, (%) | |

| Non-smoker | 17 (68) |

| Current smoker | 0 |

| Former smoker | 8 (32) |

| Nasal polyposis; n, (%) | 11 (44) |

| ABPA; n, (%) | 2 (8) |

| Bronchiectasis; n, (%) | 13 (52) |

| GERD; n, (%) | 12 (48) |

| OSA; n, (%) | 1 (4) |

| Anxiety; n, (%) | 1 (4) |

| Patients with prior biologic therapy before initiating benralizumab; n, (%) | |

| Omalizumab | 9 (36) |

| Mepolizumab | 3 (12) |

| Patients who required OCS in the 12 months prior to benralizumab initiation | 19 (76) |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1(l)(Mean; Std Dev) | 2.1; 0.8 |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1(% predicted)(Mean; Std Dev) | 71.5; 21.5 |

| FeNO (ppb)(Mean; Std Dev) | 71.5; 55.2 |

| ACT(Median [p25–p75]) | 16.5 (13–20) |

Abbreviations: n (number of patients), ABPA (Allergic Bronchopulmonary Aspergillosis), GERD (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease), OSA (Obstructive Sleep Apnoea), OCS (Oral Corticosteroid), FEV1 (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1second), FeNO (Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide), ACT (Asthma Control Test), l (litres), % predicted (percentage of predicted value), ppb (parts per billion), cells/μl (cells per microliter).

Outcomes of patients treated with benralizumab with reduced inhaled corticosteroid dosage.

| Year 1 post-biologic | Year 2 post-biologic | Year 3 post-biologic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total of patients reducing ICS(n, %) | 10 (40%) | 14 (56%) | 16 (64%) | |||||

| Baseline pre-biologic | p-Value | Year 1 post-biologic | p-Value | Year 2 post-biologic | p-Value | Year 3 post-biologic | p-Value | |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (l)(Mean; Std Dev) | 2.1; 0.8 | – | 2.3; 0.8 | 0.51 | 2.3; 0.9 | 0.44 | 2.2; 0.9 | 0.55 |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (% predicted)(Mean; Std Dev) | 71.5; 21.5 | – | 79.8; 22.5 | 0.19 | 79.8; 23.4 | 0.19 | 80.8; 20.8 | 0.13 |

| FeNO (ppb)(Mean; Std Dev) | 71.5; 55.2 | – | 57.1; 50.9 | 0.41 | 58.3; 56.3 | 0.47 | 58.7; 59.2 | 0.51 |

| ACT(Median [p25–p75]) | 16.5 (13–20) | – | 23.5 (21–25) | <0.01 | 21 (17–25) | <0.01 | 20 (15–25) | <0.01 |

| Patients who required OCS in the 12 months prior to benralizumab initiation | 19 (76) | 0.23 | 4 (44) | <0.01 | 4 (27) | <0.01 | 2 (14) | <0.01 |

| Reduction in LAMA use (n, %) | – | 3 (19) | 0.37 | 8 (50) | 0.03 | 0 (0) | 0.03 | |

| Reduction in Antileukotrienes use (n, %) | – | 2 (13) | 0.38 | 6 (40) | 0.25 | 8 (53) | 0.09 | |

Abbreviations: n (number of patients), FEV1 (Forced Expiratory Volume in 1second), FeNO (Fractional Exhaled Nitric Oxide), ACT (Asthma Control Test), LAMA (Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists), ml (millilitres), % predicted (percentage of predicted value), ppb (parts per billion).

By the end of the third year, the percentage of patients with reduced ICS doses increased slightly to 64% (n=16). However, no patients achieved low ICS doses (200–500μg of beclometasone dipropionate or its equivalent). The percentage of antileukotriene dose reduction also increased in the third year, reaching 53%. Additionally, since the initiation of benralizumab, a decrease in symptoms (measured by ACT, Table 2) and exacerbations has been observed, leading to a marked reduction in the use of oral corticosteroids (p<0.01), without any associated decline in pulmonary function over the three years of the study (Table 2).

Currently, few studies investigate optimal ICS dose adjustment strategies in difficult-to-control asthma patients initiating biologic therapy [1,3,5]. The impact of dose reduction on respiratory symptoms and pulmonary function remains unclear, making it worthwhile to examine these variables further.

National and international asthma management guidelines recommend increasing ICS doses in patients with asthma not controlled on low-dose ICS [4,6]. However, even inhaled therapies are not free from systemic risks, as a linear relationship exists between prolonged high-dose ICS use and the risk of adrenal insufficiency, diabetes, osteoporosis, and cataracts [6,7].

Studies suggest that the clinical response plateau could be at low-medium ICS doses [8,9]. In this context, randomized clinical trials have proposed that patients with severe eosinophilic asthma unresponsive to high-dose ICS may respond to lower doses once benralizumab is initiated [8]. Furthermore, according to the consensus of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, achieving the reduction of ICS to low-medium dose while maintaining good disease control, is essential to define clinical remission in asthma under treatment [10,11].

Our real-world study found that, after three years on benralizumab, 64% of patients reduced ICS to medium doses. Additionally, after three years, the use of long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMA) and leukotriene modifiers decreased by 50% and 53%, respectively.

In this cohort, treatment tapering often began with the withdrawal of LAMA therapy, while ICS reduction typically occurred at a later stage. This pattern may reflect a cautious approach in which bronchodilator therapy was adjusted first once disease control had stabilized. The observed sequence likely represents real-world prescribing behaviour rather than adherence to a predefined protocol, highlighting the need for further research to identify optimal strategies for treatment de-escalation in patients receiving biologic therapy.

Limitations of this study include the small sample size, which precludes significant conclusions about long-term pulmonary function changes. Additionally, a small amount of missing data was noted at the 3-year follow-up for some variables, including FeNO, IgE, ACT, and FEV1. These instances were infrequent and randomly distributed across the dataset, and they did not materially affect the overall conclusions. Further prospective studies with larger samples are needed to determine the effects of ICS dose reduction on pulmonary function in patients with severe asthma undergoing biologic therapy.

This study demonstrates that patients maintained significant symptom control, a reduction in exacerbations, and decreased OCS use without any decline in pulmonary function or significant increase in fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), despite reducing ICS doses within the first three years of benralizumab treatment. After analysing this finding, we observed that FeNO may emerge as a predictive biomarker of disease exacerbation in patients receiving biologic therapy in whom a reduction in ICS dosage has been achieved. An increase in FeNO levels following ICS dose tapering could potentially signal a heightened risk of dose reduction strategy failure, thereby warranting closer clinical monitoring and a tailored adjustment of inhaled therapy based on the evolving pattern of airway inflammatory activity.

Conversely, stable, or declining FeNO values may serve as a useful tool for identifying patients suitable for further progression towards low-dose ICS strategies. In our cohort, we did not observe a significant rise in this parameter that would prompt reconsideration of ICS escalation. Nonetheless, in order to assess these parameters more precisely, an extended follow-up period would be required.

In conclusion, our research work is a real-world study supporting the use of benralizumab as an effective therapeutic option to decrease the inhaled treatment burden in patients with severe asthma, enhancing disease control and reducing OCS dependency. These findings are consistent with those reported by Pini et al. (2025) [3], who also observed a progressive ICS dose reduction in a multicentre real-world setting. Unlike that study, ours provide a detailed description of stepwise de-escalation patterns, including LAMA and antileukotriene withdrawal, and highlights the potential role of FeNO monitoring during ICS tapering.

Contribution of each author| Conception | Data generation | Analysis | Revision | Approval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marta Arteaga | X | X | X | X | X |

| Laura López-Duque | X | X | X | X | X |

| Daniel Laorden | X | X | X | X | X |

| Inés Torrado | X | X | X | X | X |

| David Romero-Ribate | X | X | X | X | X |

| Elena Villamañán | X | X | X | X | X |

| Santiago Quirce | X | X | X | X | X |

| Rodolfo Álvarez-Sala | X | X | X | X | X |

| Javier Domínguez-Ortega | X | X | X | X | X |

The study was approved by the ethics committee of La Paz Hospital with (Approval code: PI-6093). It was not necessary to obtain the informed consent of the participants since, as this was a retrospective study, it was not required.

Artificial intelligence involvementNone.

Funding of the researchThe authors would like to clarify that no funding was received from AstraZeneca or any other entity for the conduct or publication of this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.