Frailty is a complex, multidimensional syndrome characterized by a loss of physiological reserves that increases a person's susceptibility to adverse health outcomes.1–3 Several studies have showed that frailty is a prevalent disorder in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients (36–47%) and that this condition is related to worse outcomes, including higher risk of exacerbations, lower health-related quality of life and mortality.3–5 Despite this, frailty has been notably absent from clinical practice guidelines. However, the recent update of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) includes frailty in the comorbidities section. This guideline defines frailty as the presence of 5 components using the Fried phenotype model: weakness, exhaustion, slow walking speed, low physical activity, and unintentional weight loss.4,6 In addition, the European Respiratory Society (ERS) has published a review of current evidence on treating frailty in adults with COPD and includes clinical management options such as geriatric care, rehabilitation, nutrition, pharmacological and psychological therapies.1

Based on this background, the COPD and Frailty project was designed to assess the degree of agreement on the diagnosis and management of frailty in COPD by a multidisciplinary group of experts using a Delphi methodology.7

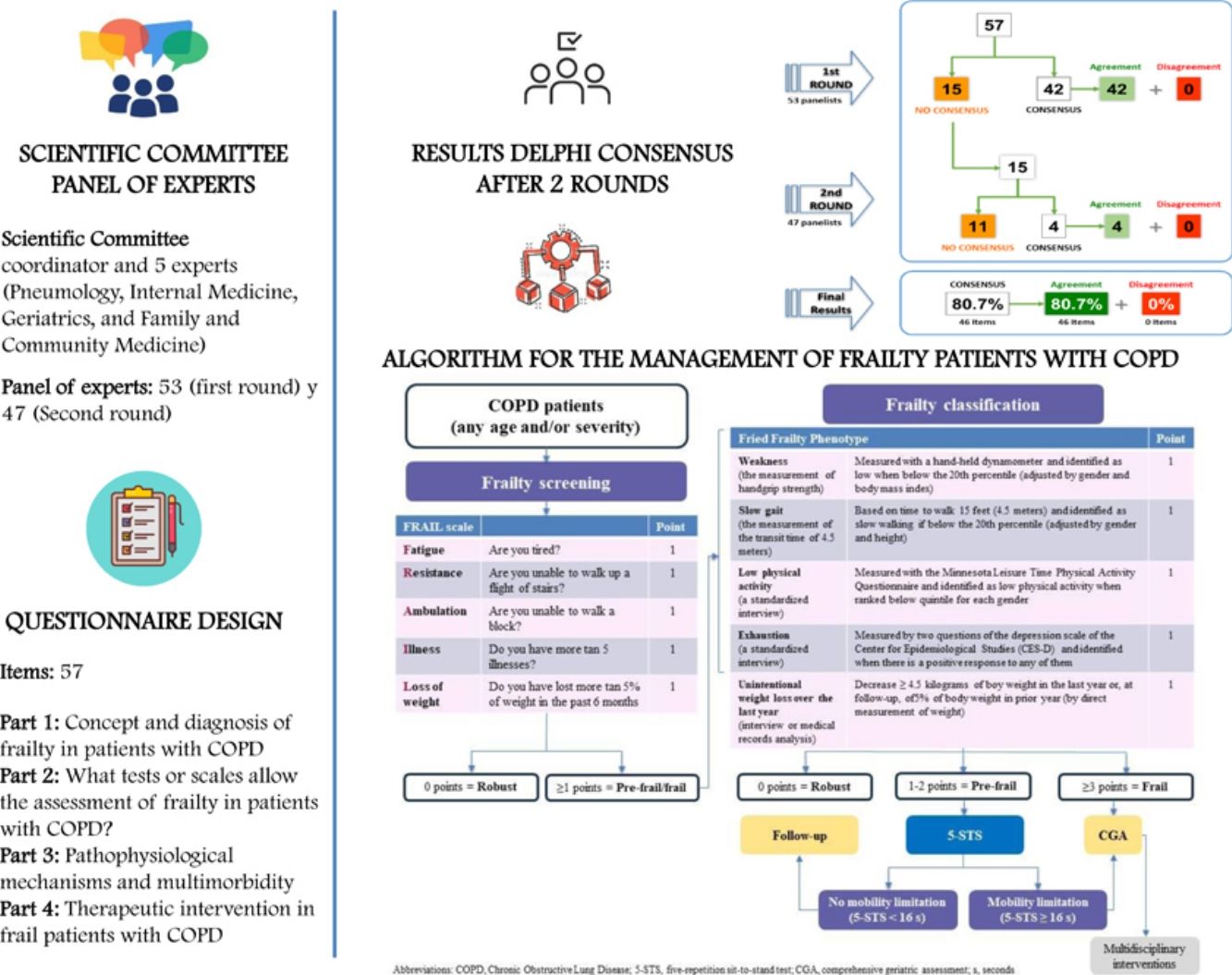

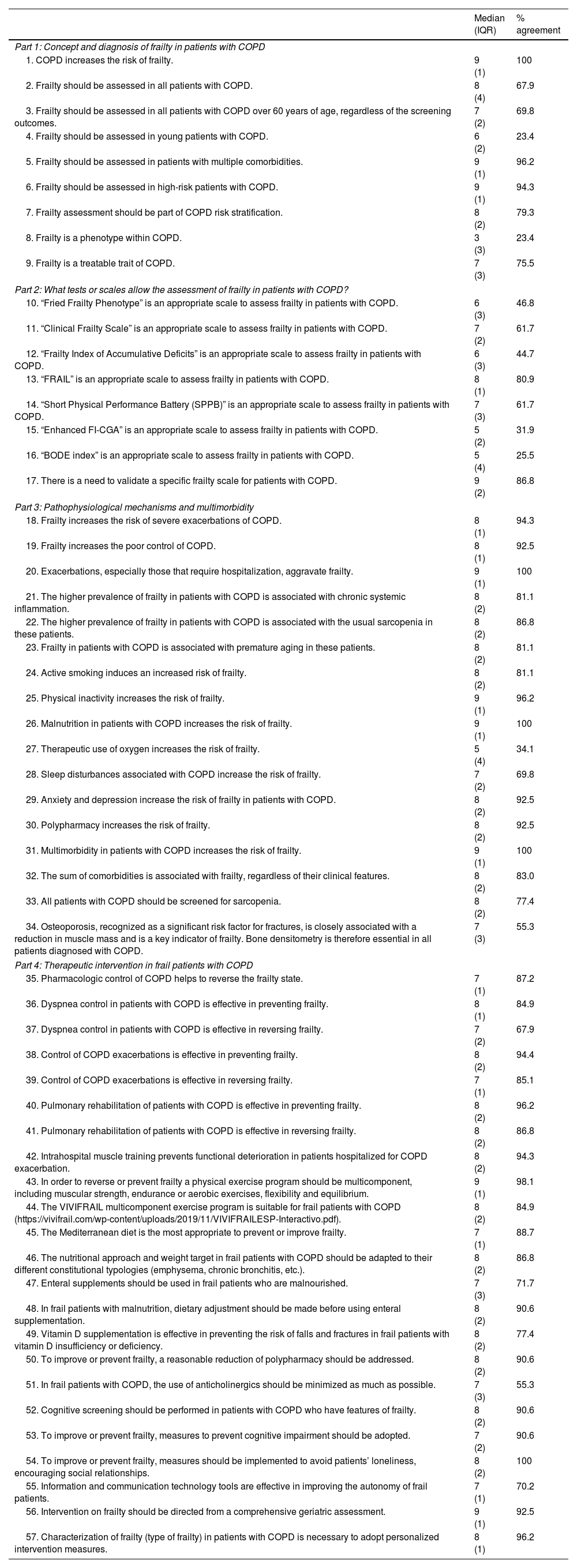

The study involved a Scientific Committee consisting of a coordinator and 5 experts (Pneumology, Internal Medicine, Geriatrics, and Family and Community Medicine), who were in charge of reviewing the most recent published evidence, identifying the topics to be discussed, and designing the Delphi questionnaire; and a panel of 47 experts of the same specialties from all over Spain, selected by the scientific committee for their experience in the management of frail patients in different settings, who showed their degree of agreement or disagreement with the items proposed in the questionnaire. Concerning the expert panel selection process, the scientific committee first identified physicians with relevant knowledge of frailty in the specialties involved. Once the experts identified, the committee invited them to participate via email, explaining the study's objective and the Delphi method used, also highlighting the paramount importance of their participation and the confidentiality of their responses. Finally, participants who showed both interest and availability were selected. The questionnaire consisted of 57 items grouped into the following topics: (1) Concept and diagnosis of frailty in patients with COPD; (2) What tests or scales allow the assessment of frailty in patients with COPD; (3) Pathophysiological mechanism and multimorbidity; and (4) Therapeutic intervention in frail patients with COPD. In order to provide an answer to the different items, a unique nine-point ordinal Likert-type scale with three groups according to the level of agreement-disagreement of the item was proposed (from 1 to 3, interpreted as rejection or disagreement; from 4 to 6, as no agreement or disagreement; and from 7 to 9, as expression of agreement or support). Consensus was reached whenever two-thirds or more of the respondents scored within the 3-point range (1–3 or 7–9) containing the median. The type of consensus achieved on each item was determined by the median value of the score. There was agreement if the median was ≥7 and, conversely, disagreement was stated whenever the median was ≤3. When the median score was included in a 4-to-6 range, the items were ‘uncertain’. The supplementary material describes a figure with the results. After two rounds, consensus was reached on 46 items (80.7%), all of them in agreement. Table 1 shows the results of the Delphi questionnaire after two rounds.

Results of the Delphi consensus after two rounds.

| Median (IQR) | % agreement | |

|---|---|---|

| Part 1: Concept and diagnosis of frailty in patients with COPD | ||

| 1. COPD increases the risk of frailty. | 9 (1) | 100 |

| 2. Frailty should be assessed in all patients with COPD. | 8 (4) | 67.9 |

| 3. Frailty should be assessed in all patients with COPD over 60 years of age, regardless of the screening outcomes. | 7 (2) | 69.8 |

| 4. Frailty should be assessed in young patients with COPD. | 6 (2) | 23.4 |

| 5. Frailty should be assessed in patients with multiple comorbidities. | 9 (1) | 96.2 |

| 6. Frailty should be assessed in high-risk patients with COPD. | 9 (1) | 94.3 |

| 7. Frailty assessment should be part of COPD risk stratification. | 8 (2) | 79.3 |

| 8. Frailty is a phenotype within COPD. | 3 (3) | 23.4 |

| 9. Frailty is a treatable trait of COPD. | 7 (3) | 75.5 |

| Part 2: What tests or scales allow the assessment of frailty in patients with COPD? | ||

| 10. “Fried Frailty Phenotype” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 6 (3) | 46.8 |

| 11. “Clinical Frailty Scale” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 7 (2) | 61.7 |

| 12. “Frailty Index of Accumulative Deficits” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 6 (3) | 44.7 |

| 13. “FRAIL” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 8 (1) | 80.9 |

| 14. “Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB)” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 7 (3) | 61.7 |

| 15. “Enhanced FI-CGA” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 5 (2) | 31.9 |

| 16. “BODE index” is an appropriate scale to assess frailty in patients with COPD. | 5 (4) | 25.5 |

| 17. There is a need to validate a specific frailty scale for patients with COPD. | 9 (2) | 86.8 |

| Part 3: Pathophysiological mechanisms and multimorbidity | ||

| 18. Frailty increases the risk of severe exacerbations of COPD. | 8 (1) | 94.3 |

| 19. Frailty increases the poor control of COPD. | 8 (1) | 92.5 |

| 20. Exacerbations, especially those that require hospitalization, aggravate frailty. | 9 (1) | 100 |

| 21. The higher prevalence of frailty in patients with COPD is associated with chronic systemic inflammation. | 8 (2) | 81.1 |

| 22. The higher prevalence of frailty in patients with COPD is associated with the usual sarcopenia in these patients. | 8 (2) | 86.8 |

| 23. Frailty in patients with COPD is associated with premature aging in these patients. | 8 (2) | 81.1 |

| 24. Active smoking induces an increased risk of frailty. | 8 (2) | 81.1 |

| 25. Physical inactivity increases the risk of frailty. | 9 (1) | 96.2 |

| 26. Malnutrition in patients with COPD increases the risk of frailty. | 9 (1) | 100 |

| 27. Therapeutic use of oxygen increases the risk of frailty. | 5 (4) | 34.1 |

| 28. Sleep disturbances associated with COPD increase the risk of frailty. | 7 (2) | 69.8 |

| 29. Anxiety and depression increase the risk of frailty in patients with COPD. | 8 (2) | 92.5 |

| 30. Polypharmacy increases the risk of frailty. | 8 (2) | 92.5 |

| 31. Multimorbidity in patients with COPD increases the risk of frailty. | 9 (1) | 100 |

| 32. The sum of comorbidities is associated with frailty, regardless of their clinical features. | 8 (2) | 83.0 |

| 33. All patients with COPD should be screened for sarcopenia. | 8 (2) | 77.4 |

| 34. Osteoporosis, recognized as a significant risk factor for fractures, is closely associated with a reduction in muscle mass and is a key indicator of frailty. Bone densitometry is therefore essential in all patients diagnosed with COPD. | 7 (3) | 55.3 |

| Part 4: Therapeutic intervention in frail patients with COPD | ||

| 35. Pharmacologic control of COPD helps to reverse the frailty state. | 7 (1) | 87.2 |

| 36. Dyspnea control in patients with COPD is effective in preventing frailty. | 8 (1) | 84.9 |

| 37. Dyspnea control in patients with COPD is effective in reversing frailty. | 7 (2) | 67.9 |

| 38. Control of COPD exacerbations is effective in preventing frailty. | 8 (2) | 94.4 |

| 39. Control of COPD exacerbations is effective in reversing frailty. | 7 (1) | 85.1 |

| 40. Pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with COPD is effective in preventing frailty. | 8 (2) | 96.2 |

| 41. Pulmonary rehabilitation of patients with COPD is effective in reversing frailty. | 8 (2) | 86.8 |

| 42. Intrahospital muscle training prevents functional deterioration in patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbation. | 8 (2) | 94.3 |

| 43. In order to reverse or prevent frailty a physical exercise program should be multicomponent, including muscular strength, endurance or aerobic exercises, flexibility and equilibrium. | 9 (1) | 98.1 |

| 44. The VIVIFRAIL multicomponent exercise program is suitable for frail patients with COPD (https://vivifrail.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/VIVIFRAILESP-Interactivo.pdf). | 8 (2) | 84.9 |

| 45. The Mediterranean diet is the most appropriate to prevent or improve frailty. | 7 (1) | 88.7 |

| 46. The nutritional approach and weight target in frail patients with COPD should be adapted to their different constitutional typologies (emphysema, chronic bronchitis, etc.). | 8 (2) | 86.8 |

| 47. Enteral supplements should be used in frail patients who are malnourished. | 7 (3) | 71.7 |

| 48. In frail patients with malnutrition, dietary adjustment should be made before using enteral supplementation. | 8 (2) | 90.6 |

| 49. Vitamin D supplementation is effective in preventing the risk of falls and fractures in frail patients with vitamin D insufficiency or deficiency. | 8 (2) | 77.4 |

| 50. To improve or prevent frailty, a reasonable reduction of polypharmacy should be addressed. | 8 (2) | 90.6 |

| 51. In frail patients with COPD, the use of anticholinergics should be minimized as much as possible. | 7 (3) | 55.3 |

| 52. Cognitive screening should be performed in patients with COPD who have features of frailty. | 8 (2) | 90.6 |

| 53. To improve or prevent frailty, measures to prevent cognitive impairment should be adopted. | 7 (2) | 90.6 |

| 54. To improve or prevent frailty, measures should be implemented to avoid patients’ loneliness, encouraging social relationships. | 8 (2) | 100 |

| 55. Information and communication technology tools are effective in improving the autonomy of frail patients. | 7 (1) | 70.2 |

| 56. Intervention on frailty should be directed from a comprehensive geriatric assessment. | 9 (1) | 92.5 |

| 57. Characterization of frailty (type of frailty) in patients with COPD is necessary to adopt personalized intervention measures. | 8 (1) | 96.2 |

Note: Green, consensus in agreement; White, without consensus.

Abbreviations: COPD, Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; BODE, Body-mass index, airway Obstruction, Dyspnea, Exercise; FI-CGA, frailty index-comprehensive geriatric assessment; IQR, interquartile range.

Regarding the concept and diagnosis of frailty in patients with COPD, there was maximum agreement that COPD increases the risk of frailty. The panelists agreed that frailty should be assessed in all patients with COPD, especially when they are older than 60 years, have multiple comorbidities, and are at high-risk. However, there was no consensus on assessing frailty in younger patients. The Scientific Committee argued that, although frailty is a concept that arises in the field of geriatrics, in both COPD and chronic diseases there is a decrease in physiological reserve leading to the appearance of frailty features in age segments where they would not be expected to be found. The panelists also agreed that frailty should be included as a factor in COPD risk stratification and to consider frailty as a treatable trait of the disease, but not a phenotype, which is consistent with the current view in the respiratory field.

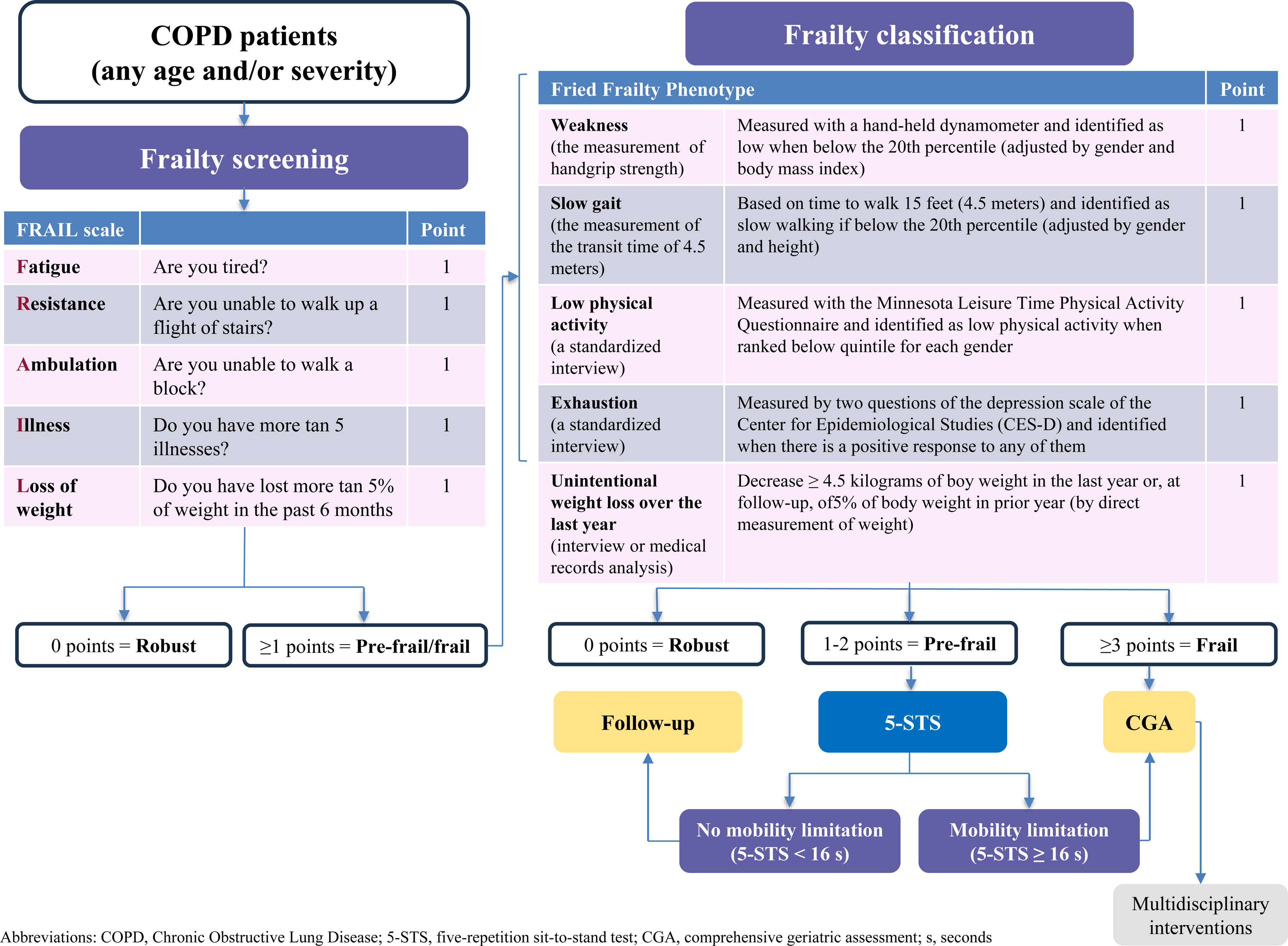

Of all the scales proposed to assess frailty in COPD, the panelists only agreed with the FRAIL scale. There was no consensus with any of the other scales (Fried Frailty Phenotype Questionnaire, Clinical Frailty Scale, Frailty Index of Accumulative Deficits, Short Physical Performance Battery, Enhanced FI-CGA, and BODE index). The panelists noted that the BODE index is a predictive index of mortality and does not assess frailty. In addition, they considered the need to validate a specific frailty scale for patients with COPD. The Scientific Committee explained that the lack of consensus with these scales may be mainly due to their lack of consideration of COPD-specific factors and also may be the difficulty of their application. Thus, the 5-item FRAIL scale (Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illnesses, and Loss of Weight) is the easiest and quickest to perform as a screening tool for frailty. This scale is an easy applicable tool, since it requires no additional materials or professional training.8,9 Notwithstanding the aforementioned, in those patients with FRAIL scale≥1 points, the scientific committee recommends the use of the Fried Frailty Phenotype for a more exhaustive study, in order to classify patients as pre-frail or frail, since it is considered the best way to objectively diagnose frailty based on its five items, and it defines the physical model of fragility and its initial conceptualization. Other scales considered useful to identify a subgroup of prefrail patients with COPD and adverse health outcomes such as mortality and hospitalization is the five-repetition sit-to-stand test (5-STS).10

Regarding pathophysiological mechanism and multimorbidity, the panelists agreed that frailty is associated with poor COPD control and increases the risk of exacerbations. Likewise, exacerbations themselves (especially severe exacerbations), comorbidities, sleep disturbances, and polypharmacy aggravate frailty. There was also agreement on the mechanisms related to higher risk of frailty in COPD, such as chronic systemic inflammation, sarcopenia, premature aging, and behavioral factors such as smoking, physical inactivity and malnutrition. There was no consensus on the use of bone densitometry in all patients with COPD. The experts argued that this lack of consensus may be explained by the fact that some panelists believe that other additional risk factors are necessary for bone densitometry in COPD patients, such as long-term glucocorticoid use, age, postmenopausal women, etc. On the other hand, it also seems likely that other panelists considered that once a fracture has occurred, the COPD patient has a very poor outcome, hence their opinion in favor of this test in these patients.

The last group of items addressed therapeutic interventions in frail patients with COPD. Almost all items reached a high degree of agreement. The panelists agreed that COPD control measures (mainly dyspnea and exacerbations) together with multidisciplinary interventions (pulmonary rehabilitation, nutritional and pharmacological measures) are effective in reducing the risk of frailty, and even reversing it. On the one hand, they considered that physical exercise in COPD patients prevents and reduces the risk of frailty. To this end, a physical training program should be multicomponent, including muscular strength, endurance or aerobic exercises, flexibility, and equilibrium. These multicomponent programs have demonstrated their effectiveness in frail older adults (e.g. VIVIFRAIL)11 They also considered that intrahospital muscle training reduces the risk of functional deterioration. On the other hand, they agreed with establishing an adequate nutritional approach, suggesting adjusting the diet rather than resorting to enteral supplements. They also agreed that reducing polypharmacy the appropriate use of treatments prevents or improves frailty status, and that measures to prevent cognitive impairment are effective in reducing the risk of frailty. Therefore, cognitive screening should be performed in patients with COPD who have features of frailty and measures should be taken to prevent loneliness by encouraging social relationships. In this regard, they considered that information and communication technologies can help to improve the autonomy of frail patients. Also noteworthy was the agreement that multidisciplinary interventions on frailty in COPD patients should be adopted after a patient-centered comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), including patients’ needs and also their values and preferences, aligning with ERS 2023 recommendations.1

Finally, according to the results of the Delphi questionnaire and considering that COPD, the Scientific Committee developed an algorithm for the management of frailty in patients with COPD (Fig. 1). Initially, COPD patients should undergo a simple screening using the FRAIL scale. Those patients with FRAIL scale≥1 points should be classified as pre-frail or frail (using the Fried Frailty Phenotype).6 Subsequently, pre-frail COPD patients should be additionally classified based on their potential mobility limitation (using the 5-STS), since those patients are at risk for poor outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 2).10 In the case of frailty or pre-frailty subjects with mobility limitation, patient-centered CGA and tailored multidisciplinary interventions should be implemented.

In conclusion, the current document endorses the idea that frailty is a common condition in patients with COPD, leading to significant adverse repercussions. Therefore, a regular assessment of frailty is recommended in all patients with COPD, and a multidisciplinary diagnostic approach is suggested for patients with COPD and frailty.

Contribution of each authorAll authors were involved in the conception and design of the work; acquisition, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting the work, revising it critically for important intellectual content.

List of researchersThe authors have specifically collaborated in the drafting of this article and are not part of an established research group.

Artificial intelligence involvementNothing in the study was developed with the help of any artificial intelligence software or tool.

Funding of the researchThe study was supported by Faes Farma (Spain).

Conflicts of interestRBM has no conflicts of interest, beyond the participation in the group of experts-authors of this project, supported by the pharmaceutical laboratory Faes Farma.

PCR has no conflicts of interest, beyond the participation in the group of experts-authors of this project, supported by the pharmaceutical laboratory Faes Farma.

IML has no conflicts of interest, beyond the participation in the group of experts-authors of this project, supported by the pharmaceutical laboratory Faes Farma.

ENS has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, and Menarini; and consulting fees from Bial and FAES.

JJJSC has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Bial, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, FAES, GSK, Menarini, and Novartis; consulting fees from Bial, Chiesi, FAES, and GSK; and grants from GSK.

FJTS has no conflicts of interest, beyond the participation in the group of experts-authors of this project, supported by the pharmaceutical laboratory Faes Farma.

The authors would like to thank Fernando Sánchez Barbero PhD and Luzán 5 Health Consulting for their help in the preparation of the manuscript.