Everyone is aware of the consolidated potential of the donation–transplantation duo established in Spanish healthcare. Among the avenues for growth in order to continue improving and to be able to offer transplants to all patients who need them, is the asystole donation modality [1–3]. In 2024, the importance of controlled donation after circulatory death (cDCD) was once again demonstrated in the growth experienced: with a total of 1316 donors after controlled circulatory death (25% more than in 2023), this type of donation already represents more than half of the donors in Spain [4,5]. In addition, this type of donation is consolidating as a multi-organ donation, thanks to the generalization in Spanish hospitals of a complex organ preservation procedure based on extracorporeal circulation devices (ECMO) [6–9]. But the growing demand for organs and tissues for transplantation requires the exploration of new clinical spaces that allow the identification of potential donors, especially outside the units traditionally involved, such as Intensive Care Units (ICU) [9–11]. In this context, Intermediate Respiratory Care Units (IRCU), promoted after the COVID-19 pandemic to care for semi-critical respiratory patients, emerge as an area with potential for detecting potential donors after controlled circulatory death and tissue donation [12,13].

In our country, organ donation is considered part of the overall care of a patient at the end of life [3]. Therefore, all healthcare professionals should consider donation as an option when treating a patient with a limited short or medium-term life prognosis or who is already dying, provided there are no absolute contraindications or evidence of refusal to donate. This not only allows the dying patient to become a donor if it is in line with their values and principles, but also helps to increase transplantation options for patients in need [14–16].

The objective of this study was to evaluate the qualitative and quantitative impact of an educational and organizational intervention for the staff of an IRCU, with a view to improving the detection of potential donors and increasing the rate of effective donors. A prospective observational study was conducted in the IRCU of the Respiratory Department of a tertiary-level university hospital between January and November 2024. The intervention encompassed a two-hour specific training sessions designed to equip both medical and nursing staff, focusing on motivation, conceptual definitions, and clarification of inclusion criteria and contraindications, providing the necessary skills to identify potential donors, effectively communicate with their relatives, conduct donation interviews, and liaise with the Donor Transplant Coordination Unit. Finally it included case-based discussions (real or hypothetical) to enhance confidence and competence in identifying potential donors and integrating donation processes into daily clinical practice. In addition, a standardized protocol was designed and implemented in collaboration with the Donor Transplant Coordination Unit, to identify and manage potential donors after circulatory death. It includes early detection based on clinical criteria, exclusion of contraindications, and activation of the transplant coordination team. Family discussions are conducted jointly by Donor Transplant Coordination Unit an medical/nursing staff, ensuring understanding of the terminal condition and donation process. Informed consent is obtained for organ and tissue donation and for procedures to preserve graft viability. Cannulas and catheters are placed before withdrawal of life-sustaining therapies (WLST). Following cardiac arrest, death is certified after 5min, and organ preservation measures begin. If death occurs within 120min of WLST, organ retrieval proceeds; otherwise, tissue donation is considered.

The study period was characterized by a comprehensive analysis encompassing the identification of potential donors, the conversion of these donors into effective donors, and the clinical characteristics of patients evaluated. The analysis also encompassed the identification of the primary reasons for non-conversion to effective donors. A descriptive comparison with previous annual periods was also performed.

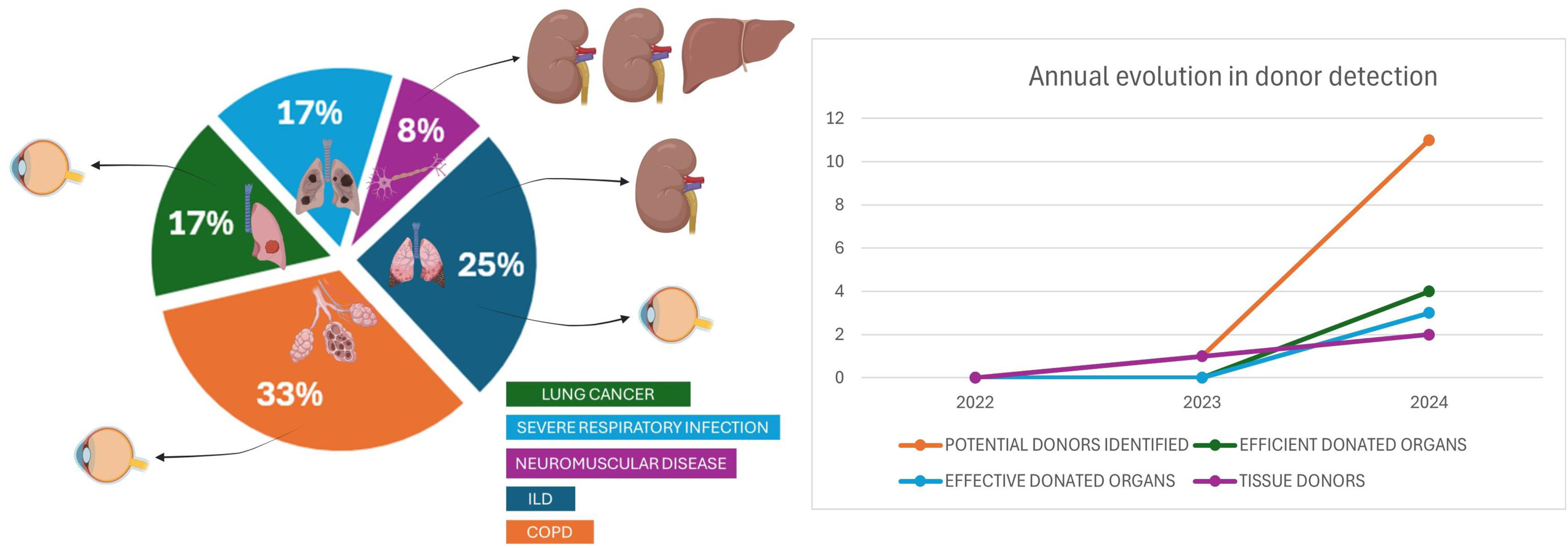

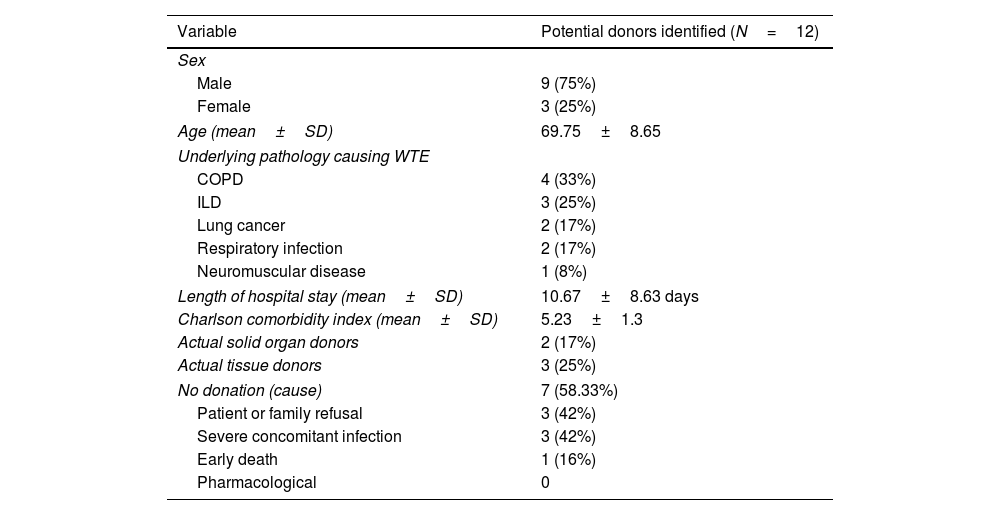

During the period under scrutiny, a total of 12 potential donors were identified, with a mean age of 70 years (69.75±8.65) and a mean Charlson comorbidity index of 5.23±1.3. Of these, 75% were male (Table 1). This number of patients represents a substantial increase compared to previous years, when there was hardly any activity in this area. Of these, 41% eventually became effective organ or tissue donors. The most prevalent pathology leading to the withdrawal of therapeutic efforts and subsequent detection of potential donation was chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (33%), followed by interstitial lung disease (ILD) (25%), lung cancer (17%), severe respiratory infection (17%), and neuromuscular disease (8%). However, the rate of effective organ donation per potential donor detected was higher in neuromuscular patients and in patients with COPD (200% and 25% respectively) and the conversion rate in the case of tissue donation was higher in patients with lung cancer (50%) and COPD (33%). On a global scale and in comparison with preceding years, the aggregate number of effective donations escalated by 400% for organs and 200% for tissues (Fig. 1).

Baseline characteristics of the potential donors identified during the study period.

| Variable | Potential donors identified (N=12) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 9 (75%) |

| Female | 3 (25%) |

| Age (mean±SD) | 69.75±8.65 |

| Underlying pathology causing WTE | |

| COPD | 4 (33%) |

| ILD | 3 (25%) |

| Lung cancer | 2 (17%) |

| Respiratory infection | 2 (17%) |

| Neuromuscular disease | 1 (8%) |

| Length of hospital stay (mean±SD) | 10.67±8.63 days |

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean±SD) | 5.23±1.3 |

| Actual solid organ donors | 2 (17%) |

| Actual tissue donors | 3 (25%) |

| No donation (cause) | 7 (58.33%) |

| Patient or family refusal | 3 (42%) |

| Severe concomitant infection | 3 (42%) |

| Early death | 1 (16%) |

| Pharmacological | 0 |

WTE: withdrawal of life support, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ILD: interstitial lung disease, SD: standard deviation.

Preliminary follow-up data confirm that most of the solid organs retrieved from donors identified in our intermediate care unit were successfully transplanted, with favorable post-transplant outcomes. Although one kidney and one liver were ultimately discarded due to suboptimal histological or perfusion findings, the remaining kidneys were implanted in highly sensitized or complex recipients and remain functional to date. Regarding ocular tissues, six corneas were retrieved: three were successfully implanted, one was allocated for research, and two were discarded due to inconclusive serology. These results support the clinical feasibility and effectiveness of identifying controlled donation after circulatory death (cDCD) donors in intermediate care settings.

A subsequent analysis was conducted in order to ascertain the primary reasons for rejection or non-inclusion of patients who were detected as potential donors but who were ultimately not accepted. This analysis revealed that the most prevalent cause of refusal was the patient or family (42%), followed by concomitant infection (42%) and early exitus (16%). The project also identified specific barriers to donor identification in the UCRI, including a lack of clear protocols and specific training. The educational and organizational intervention successfully addressed these barriers, promoted the creation of a pro-donation culture and strengthened the active role of healthcare staff in the early identification and management of the donation process. Specific training and the establishment of clear protocols proved to be highly effective strategies to significantly improve the identification and management of potential donors after controlled circulatory death and tissue donation in IRCU [16–18]. This pilot study could serve as a replicable model in other similar care units, helping to increase organ and tissue availability and improve end-of-life care.

In conclusion, the results obtained confirm that properly trained and organized IRCUs represent a valuable area of care to increase the detection of potential donors. Widespread implementation of similar initiatives could have a significant impact on the availability of organs and tissues for transplantation, directly benefiting many patients on the waiting list. Recognizing organ donation as an integral component of end-of-life care and allowing patients to maintain autonomy in end-of-life decisions regarding the possibility of becoming organ donors.

Authors’ contributionsAlejandro Romero-Linares, Jose M. Pérez-Villares and Jose A. Sánchez-Martínez conceived the study, collected data, and drafted the manuscript. Antonio Cárdenas-Cruz and Jose M. Pérez-Villares contributed to the study design and data collection. Patricia Fuentes-García collaborated in data interpretation and educational sessions for the healthcare staff of the “Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit (IRCU)”. Bernardino Alcázar-Navarrete critically revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT in order to improve language and readability. After using this tool/service, the author(s) reviewed and edited the content as needed and take(s) full responsibility for the content of the publication.

FundingNo external funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Uncited reference[19].

We thank the staff of the Intermediate Respiratory Care Unit and the Donor Coordination Team for their collaboration in this project.