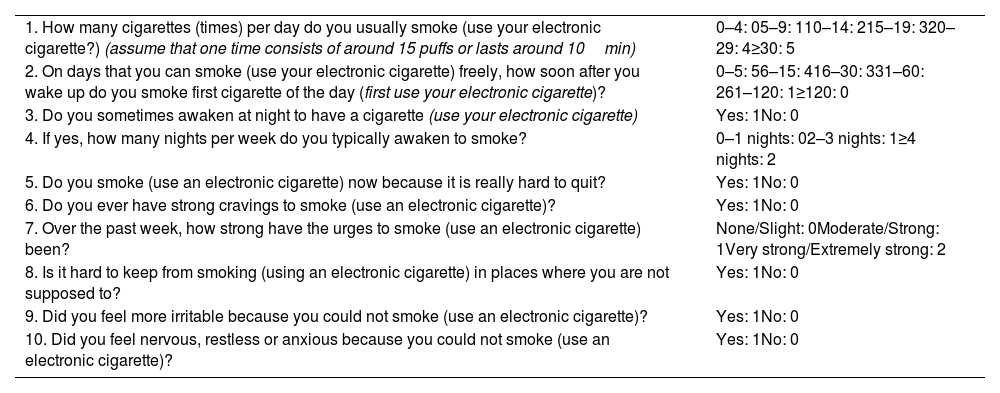

The use of new tobacco and nicotine products (electronic nicotine delivery system, heated tobacco, and smoking water pipes) has increased in recent years worldwide. This has led to the emergence of a new smoker profile whose diagnostic and therapeutic approach is different from that of conventional tobacco smokers. The demand for help in quitting these new forms of smoking necessitates the development of guidelines or recommendations that are not currently available. Therefore, the Tobacco Control Group of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) and in collaboration with Ibero American societies (AAMR, ALAT, ASONEUMOCITO, SNMCT) have produced a consensus document using the nominal focus group methodology, supported by a narrative review on the approach to smoking in users of electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) and new forms of tobacco. The approach to diagnosing these types of users will be based on variables such as intensity, degree of nicotine dependence, self-efficacy, and motivation, using new scales or questionnaires. Psychological counseling will be based on psychoeducation, motivational interviewing, and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, cytisinicline, and burpropion are medications to consider for users of these devices.

New forms of tobacco and nicotine consumption are understood as those methods of supplying tobacco and nicotine that have been developed intensively in recent years, thanks to a novel strategy by multinational tobacco companies to promote and relaunch tobacco use in society. We refer specifically to three new forms of consumption: electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS), heated tobacco, and Smoking Water Pipes [1–5].

ENDS are electronic devices for supplying nicotine (not tobacco). The most recent data show that their use has increased dramatically in the general population, and especially among younger groups [1]. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of ENDS use shows that 11% of men and 8% of women worldwide use them. Europe is the continent with the highest prevalence, 14%, followed by Asia (11%) and the Americas (10%).

Heated tobacco is a new product that, according to the tobacco companies that produce and promote it, heats tobacco, but does not burn it. This would mean, according to them, a reduction in toxic substances. This claim has not been proven in independent studies [2]. There are studies that observe user profiles of this type of device with specific characteristics. They tend to be young users, with a high socioeconomic status, with a greater predisposition to alcohol and other drug use, and with the intention of quitting smoking or even having recently quit. Data in Spain show a marked increase in monthly sales, which have multiplied by nine between January 2017 and July 2018 (from €419,942 to €4,189,859 monthly sales, respectively) [3].

The smoking water pipe or hookah (shisha, hookah, narghile, or Turkish pipe) is a device widely used in the Middle East. Its use has spread in recent years in Western countries, especially in recreational settings. The ESTUDES study found that 57.9% of students admitted to having used a smoking water pipe at some point in their lives [4]. In 2018, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in its Global Progress Report estimated that the smoking water pipe was available in 69% of countries, compared to 61% in 2016. Many of these countries were in the Latin American region [5].

By using all of these products, users achieve blood levels of nicotine similar to those obtained with conventional cigarettes [6,7]. Therefore, these devices are just as addictive as conventional cigarettes. This is evident in the case of ENDS and tobacco heaters. These contain tobacco with the same amount of nicotine as manufactured tobacco [8]; and a review of studies on the use of ENDS for smoking cessation found that the pooled prevalence of continued use beyond 6 months was 54% (95% CI: 46–61%). Among ENDS users who had quit conventional tobacco, 70% continued to use them beyond the first six months after quitting (95% CI: 53–82%, I2 73%, N=215). That is, compared to those who used smoking cessation medications, patients who used ENDS maintained smoking for 6 months or more [9]. This clearly demonstrates the dependence-causing potential of these devices.

The increased use of these new tobacco consumption devices and their high addictive potential is leading some users to seek help from healthcare professionals to quit smoking [10]. Healthcare assistance for these patients has become a challenge not only in terms of how to make an adequate clinical and analytical diagnosis, and determine the types of dependencies they experience due to the use of these devices, but also in terms of what type of psychological counseling and pharmacological treatment can be provided to help them quit using them.

There is no rigorous scientific evidence on how to assess the intensity of use or the different degrees and types of dependence that users may experience; there is also no reliable data on the assessment of different biochemical markers in these patients or on the efficacy and safety of psychological counseling and standard pharmacological treatments to help users quit using them.

For all these reasons, a group of Tobacco Cessation experts representing five Ibero-American scientific societies (Argentine Association of Respiratory Medicine AAMR, Latin American Thoracic Association, ALAT, Colombian Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery, ASONEUMOCITO, Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery, SEPAR and Mexican Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery, SMNCT) decided to prepare this consensus document, which will be a pioneer in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to users of new nicotine or tobacco products: ENDS, tobacco heated and smoking water pipes.

MethodologyGiven the limited scientific evidence on the assessment and treatment of users of new forms of tobacco and nicotine, an expert consensus was considered. The methodology used was as follows.

Study designConsensus was reached using a nominal focus group methodology, assisted by a narrative review of the scientific literature on the management of nicotine dependence in ENDS users and smokers of new forms of tobacco. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki regarding medical research involving human subjects and in accordance with applicable regulations on Good Clinical Practice.

Participant selection and first nominal group meetingFirst, a group of smoking experts from the Tobacco Control Group of the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), the sponsoring society of the document, were selected. Additional experts from four Ibero-American scientific pulmonology societies were added to this group: AAMR, ALAT, ASONEUMOCITO, and SMNCT. This selection was approved by the SEPAR Document Management Committee. Following this, and under methodological supervision, the objectives, scope, users, sections, and topics to be developed in the document were defined. Based on this, a narrative review of the literature was designed.

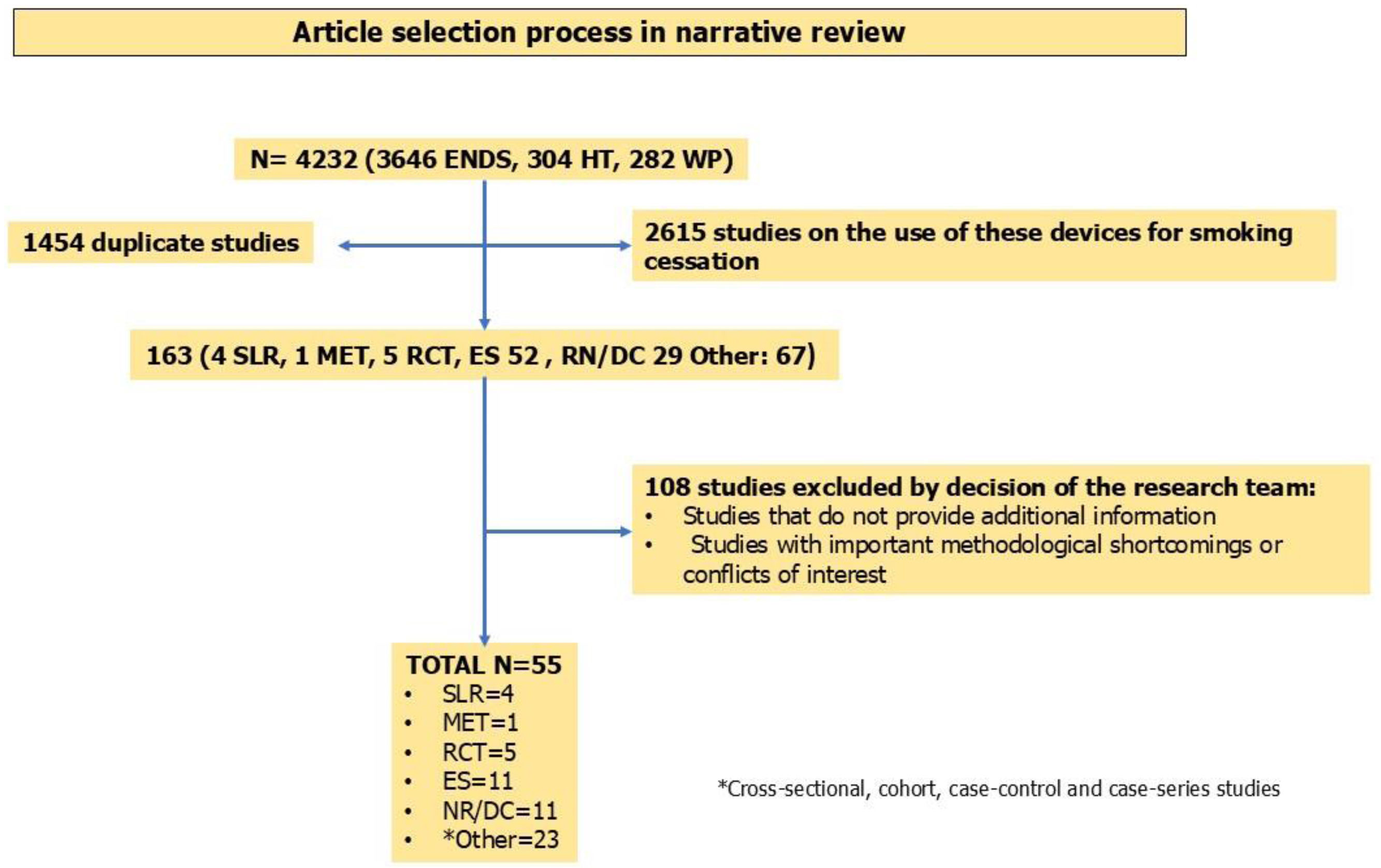

Narrative literature reviewMedline was searched using the Clinical Queries tool of Pubmed, Embase and Scopus with controlled language (Mesh) and with the following terms (until February 2025): “e-cigarettes”, Electronic Nicotine Devices System (ENDS), IQOS, waterpipe, diagnosis, treatment, heated tobacco. The objective was to identify articles that analyzed the following aspects of new tobacco and nicotine products: (a) Clinical and analytical assessments, nicotine dependence and treatment of electronic cigarette users. (b) Clinical, analytical assessments and nicotine dependence of heated tobacco smokers. (c) Clinical, analytical assessments and nicotine dependence of waterpipe smokers. Systematic literature reviews, narrative reviews, consensus documents, randomized clinical trials and studies based on routine clinical practice were selected. Duplicate articles, studies referring to the use of these devices for smoking cessation, and manuscripts based on the methodological team's criteria were excluded. Fig. 1 shows a diagram of the study selection.

The assessment of the risks of bias of the studies included in the narrative review was performed using several tools. The AMSTAR-2 tool was used to analyze the quality of systematic reviews. The ROBINS-E (“Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies – of Exposure”) tool is used to assess the risk of bias in estimates effect of exposure (ENDS, heated tobacco, smoking water pipe) in observational studies. The ROBINS-I (“Risk of Bias in Non-Randomized Studies – of Interventions”) tool is used to assess the risk of bias in estimates of the effectiveness or safety of vaping cessation interventions in non-randomized studies. We used the RoB2 (Version 2 of the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomized trials) tool to assess the risk of bias in randomized trials o vaping cessation (Tables 1S–4S supplementary material).

With all this information, a series of general principles, recommendations, and preliminary algorithms were generated.

Nominal meetings and editing of the final documentAll of this was shared with all members of the nominal group, allowing each of them to make corrections and comments. The modifications made were shared again, and once approved by all group members in a nominal meeting, the document was considered final.

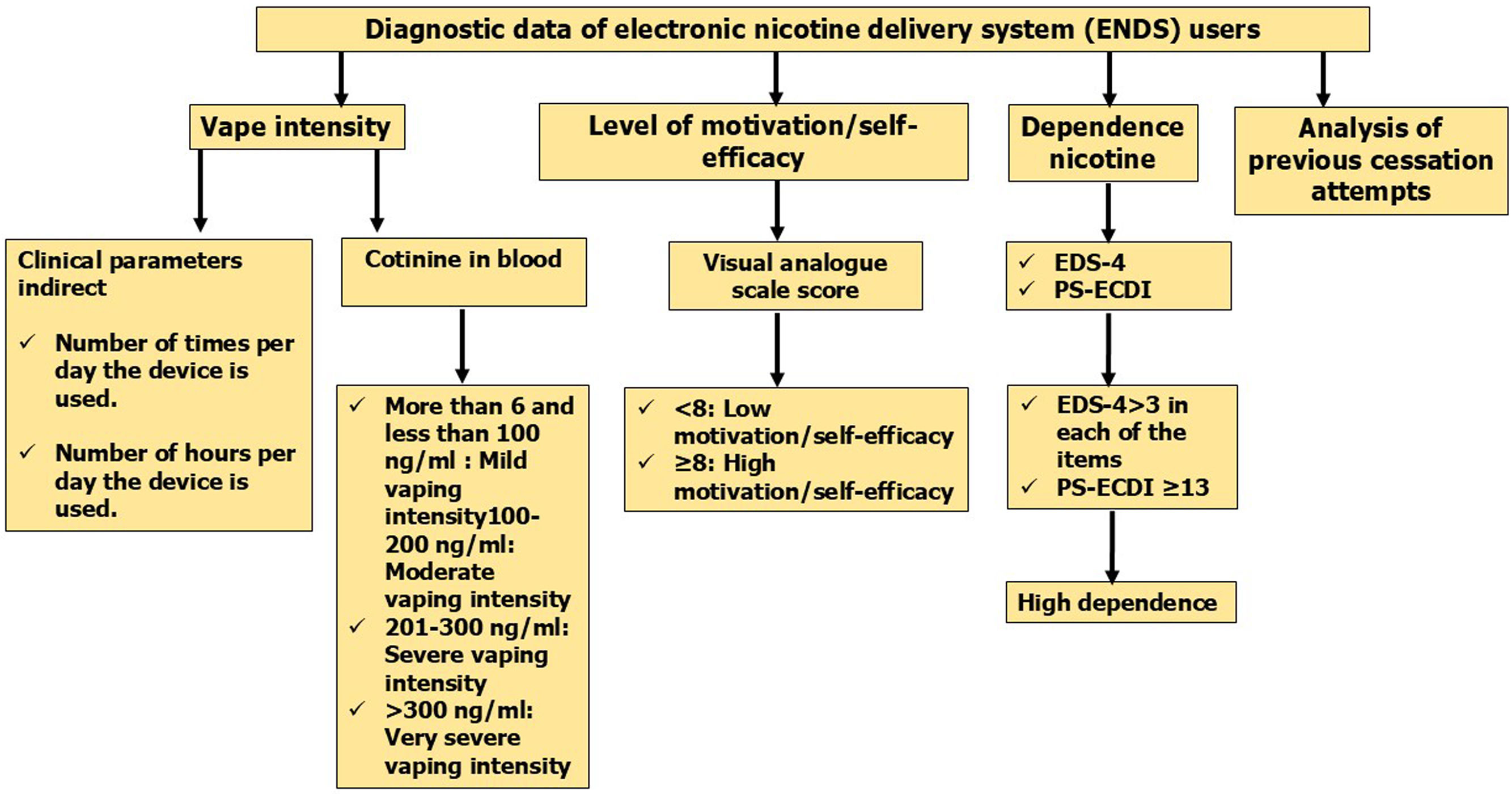

Assessments in ENDS usersMeasuring consumption intensity in ENDS usersMeasuring the degree of vaping can be determined by several factors: the type of vape used, the concentration of nicotine in the liquid, the number of daily charges used by the vaper, and the number and characteristics of the puffs the vaper takes from the device. However, some studies have found that the most appropriate indirect method for measuring the degree of vaping is to ask users of these devices about the number of times or the number of hours they use them per day [6,11,12]. The answers given by users to these questions are very well related to the levels of cotinine in their blood: a more intense use of these devices, reflected by a greater number of times per day of use or a higher number of hours per day of use, will translate into higher blood cotinine levels [6,11,12]. Addicot et al. found in their work analyzing the relationship between blood cotinine levels and the number of times or hours per day of use of ENDS, a significant correlation [6]. Plasma cotinine levels ranged from a minimum of 25ng/mL to a maximum of 500ng/mL, with the highest number of determinations being between 75 and 400ng/mL. It has been determined that blood cotinine levels above 6ng/mL is the cut-off point that differentiates a smoker from a non-smoker [13]. On the other hand, it should be noted that up to 60% of vapers also use conventional cigarettes. Their use should also be taken into account when correctly measuring the degree of vaping [6,11,12].

Considering all these data, the proposal for indirect measurement of vaping intensity would be to ask users of these devices about the number of times per day and the number of hours per day they use them. One time of using an ENDS should be defined as using it for 10min [6,14–16]. For direct measurement, blood cotinine determination is highly recommended, with a cut-off point of more than 6ng/mL [13]. The use of indirect methods will be useful in primary care settings, while direct methods are most recommended in specialized units [6,11–13].

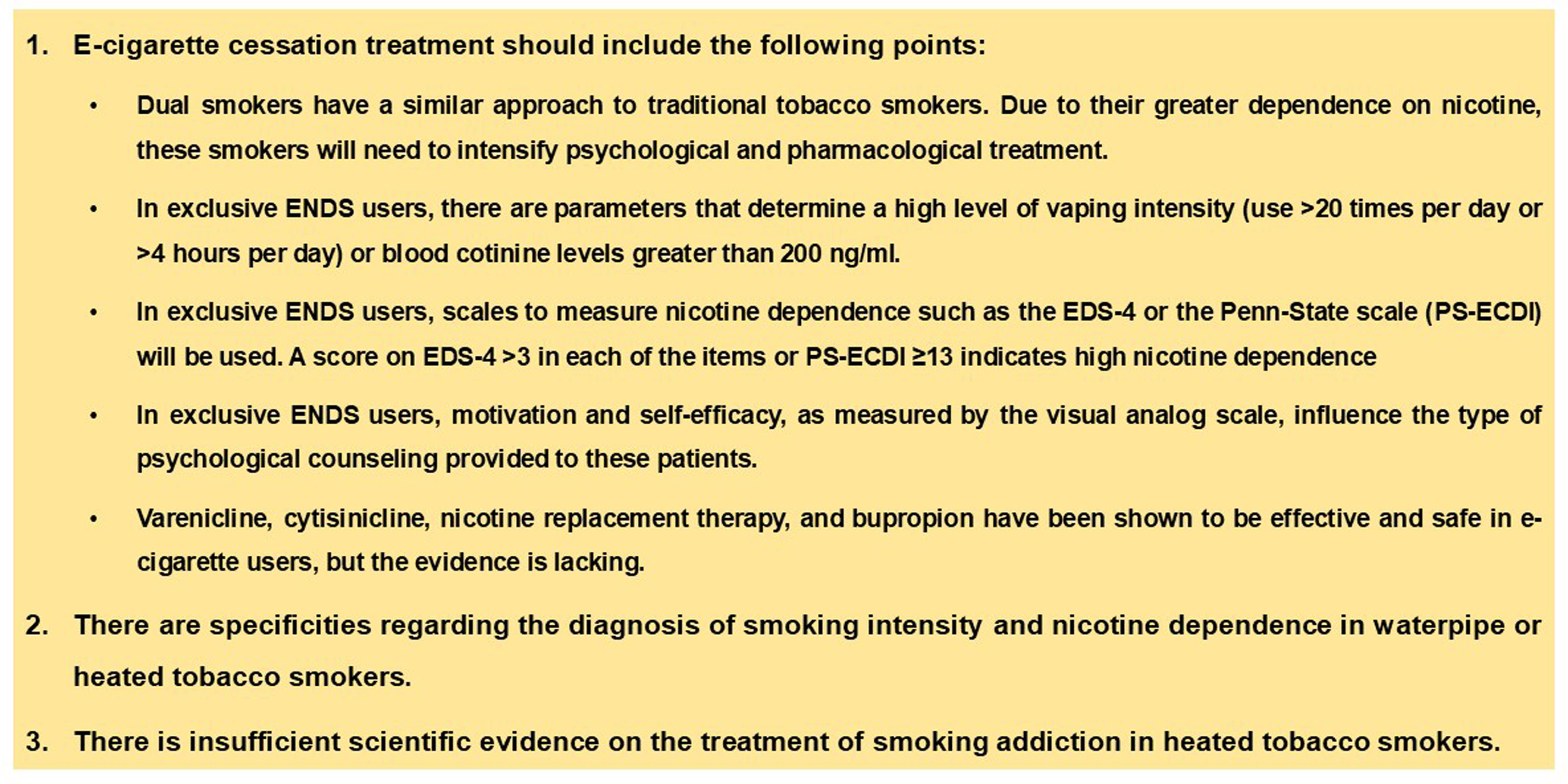

Table 1 shows a scale that can be used to classify vapers based on their intensity. We propose that plasma cotinine levels could be the most specific parameter for measuring vaping intensity [6,11–16]. It should be noted that the cutoff points shown are decisions made by the authors of this consensus document based on the studies referenced in the citations provided.

Assessment of vaping intensity in exclusive electronic cigarette users.

| 1. By number of times per day the electronic cigarette is used (Understanding one time as using the device for 10min)•. Less than 10 times per day: Mild vaping intensity•. Between 10 and 19 times per day: Moderate vaping intensity•. Between 20 and 29 times per day: Severe vaping intensity•. 30 or more times per day: Very severe vaping intensity2. By number of hours per day using the electronic cigarette•. Less than two hours per day: Mild vaping intensity•. Between two and less than four hours per day: Moderate vaping intensity•. Between four and less than six hours per day: Severe vaping intensity•. Six or more hours per day: Very severe vaping intensity3. By plasma cotinine levels•. More than 6 and less than 100ng/ml: Mild vaping intensity•. 100–200ng/ml: Moderate vaping intensity•. 201–300ng/ml: Severe vaping intensity•. 300ng/ml: Very severe vaping intensity |

There are several scales for measuring the degree of physical dependence on nicotine in vapers: Penn State E-Cigarette Dependence Index (PS-ECDI); E-Cigarette Dependence Scale (EDS-4); and Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) adapted for ENDS (e-FTCD). e-FTCD is an adaptation of the FTCD by changing the word “cigarettes” to “ENDS” and the word “smoking” to “vaping.” The result is calculated by summing the scores obtained for each response (Table 5S, supplementary material) [15,16]. Of these, the validated questionnaires for physical dependence on nicotine in vapers are EDS-4 and PS-ECDI.

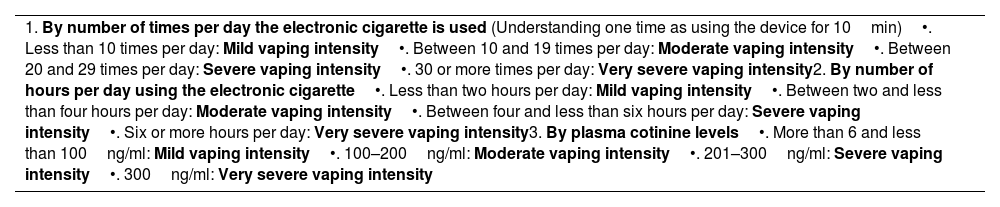

EDS-4 is adapted from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) for tobacco dependence and has three versions: one with 22 items, another with 8 items, and another with 4 items. All of these have been validated for measuring ENDS dependence in youth and adults. The 4-item scale is as valid as the longer versions for determining ENDS dependence (Table 1) [17].

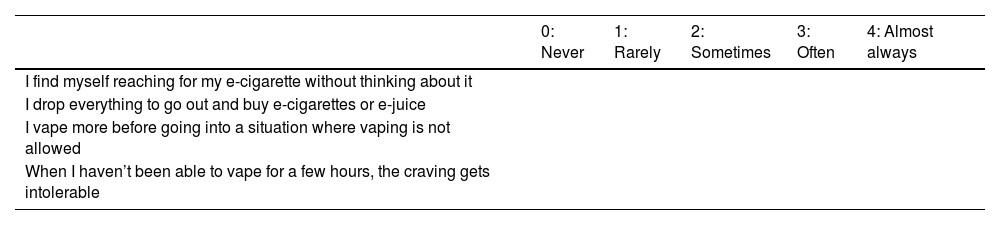

PS-ECDI is an e-cigarette modification of Penn State Nicotine Dependence Index. It is a validated 10-item scale for measuring ENDS dependence. The scale contains questions measuring different dependence constructs such as: time to first cigarette, number of times vaping per day, craving rating, irritability, and waking up at night to vape. A final score of 13 or more indicates a high level of dependence (Table 2) [18].

Electronic Cigarette Dependence Scale (EDS-4).

| 0: Never | 1: Rarely | 2: Sometimes | 3: Often | 4: Almost always | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I find myself reaching for my e-cigarette without thinking about it | |||||

| I drop everything to go out and buy e-cigarettes or e-juice | |||||

| I vape more before going into a situation where vaping is not allowed | |||||

| When I haven’t been able to vape for a few hours, the craving gets intolerable |

A score higher than 3 on any of the items in the EDS-4 scale indicates high nicotine dependence.

The three scales (e-FTCD, EDS-4 and PS-ECDI) have strong internal consistency, in all cases above 0.50, although e-FTCD has the lowest internal consistency [15]. Likewise, all of them have adequate reliability results and in the structure analyses [15,18,19]. However, PS-ECDI is a test that, when administered, provides excellent clinical data to healthcare professional that can be used for a better clinical assessment of the vaper. A drawback of this test could be its length (10 items) compared to only 4 items of EDS-4. We recommend using one of the two scales: EDS-4 or PS-ECDI for the analysis of physical dependence on nicotine in ENDS users. It is important to highlight that neither of these questionnaires has been validated in Spanish at this time. Therefore, this recommendation is not evidence-based, but we believe it should be very useful for daily clinical practice and that its joint use by the group of Spanish-speaking researchers will facilitate the fast validation of these questionnaires in Spanish.

When assessing dependence, it is important to consider whether the subjects are dual smokers. Dual smokers are known to be more dependent on conventional cigarettes than on ENDS; greater dependence or intensity of conventional cigarette use predicts less dependence or intensity of ENDS use [15]. Therefore, in dual smokers, FTCD scale should be used in addition to one of the ENDS-specific scales (EDS-4 or PS-ECDI). It would be enough for any of these scales to assess the patient as highly dependent for him or her to receive treatment as such.

Measuring motivation and self-efficacy to quit ENDSThe results of studies analyzing vapers’ motivation to quit ENDS are heterogeneous. One study showed that up to 90% of long-time vapers did not want to quit ENDS [20]. On the other hand, it is known that most dual smokers convert to smoking only conventional cigarettes [21]. A qualitative study investigated vapers’ attitudes found that the most relevant topics for most of these subjects were related to quitting vaping and seeking medical help [22]. Given this heterogeneity, we recommend using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) as the best method to analyze motivation in vapers. A VAS score≥8 would define high motivation to make a serious quit attempt.

In addition to assessing motivation to quit ENDS, it is advisable to evaluate the subject's self-efficacy for quitting these devices. The use of VAS is also recommended for this assessment. A VAS score≥8 defines high self-efficacy for quitting ENDS. This variable, in particular, has been reported to predict attempts to quit vaping (OR: 1.33 (1.01–1.74)) [23].

It is important to note that VAS has not been validated as an adequate scale for measuring motivation and self-efficacy to quit vaping. Therefore, this recommendation is not evidence-based, but we believe it should be very useful for daily clinical practice and that its joint use by the group of Spanish-speaking researchers will facilitate the fast validation of this scale in Spanish.

Analysis of previous attempts to quit using ENDSIn the case of previous attempts to quit ENDS, data should be collected such as the number of attempts, the method used, the pharmacological treatment used, the cause of relapse, and the duration of abstinence. It is also advisable to ask the subject about any changes in the characteristics of the ENDS used (nicotine concentration and duration of use of the devices). Fig. 2 summarizes the activities that must be performed to make an adequate assessment of vapers.

Assessment of heated tobacco smokersAssessment of these smokers will be based on the following factors: measuring smoking intensity, measuring the degree of physical dependence, measuring motivation and self-efficacy to quit these devices, and analyzing previous quit attempts.

Direct methods can be used to measure smoking intensity: levels of CO in expired air and cotinine levels determination. Although the manufacturers of these products state that their use does not produce combustion, a recent study conducted in Spain demonstrated, using a simple test, that the use of these devices does produce combustion and releases carbon monoxide, albeit in very low quantities [24]. Therefore, for exclusive users of heated tobacco, in order to obtain a more precise assessment of smoking intensity, it is recommended first to determine cotinine in body fluids, and it is preferable to postpone the measurement of CO in expired air only to those cases in which there is combined consumption of conventional cigarettes and heated tobacco. Indirect methods can also be used. In this case, the patient should be asked about the number of heated tobacco cigarettes used per day. It should be noted that each “heated tobacco cigarette” contains between 0.3 and 0.5mg of nicotine and that the cotinine levels obtained in the blood by a user of this type of cigarette as a result of its use are similar to those obtained by smoking a conventional cigarette [25]. Table 6S supplementary material shows how to correctly assess smoking intensity in heated tobacco users. The cut-off points shown are decisions made by the authors of this consensus based on the studies referenced in the citations provided.

To measure nicotine dependence in heated tobacco users, we can use FTCD, taking into account that a “heated tobacco cigarette” can be considered a conventional cigarette. This statement is fully justified since the nicotine levels in each “heated tobacco cigarette” are similar to those found in conventional cigarettes, and the cotinine levels obtained by heated tobacco users are similar to those obtained by conventional cigarette users [25,26]. Table 7S supplementary material shows the FTCD adapted to heated tobacco users.

Motivation and self-efficacy can be measured in these patients using VAS. A score of 8 or higher indicates high levels of motivation and self-efficacy to discontinue using this device.

It is important to note that neither FTCD nor VAS have been validated for determining physical dependence or degree of motivation or self-efficacy to quit heated tobacco cigarettes. Therefore, these recommendations are not evidence-based, but we believe they should be very useful for daily clinical practice and that its joint use by the group of Spanish-speaking researchers will facilitate the fast validation of these scales in Spanish. The analysis of quit attempts in heated tobacco users will follow the same guidelines as for conventional cigarette users.

Assessment of smoking water pipe usersUsers of this device inhale high concentrations of nicotine, tar, and CO. All of this leads to these users developing nicotine dependence and difficulty quitting [27].

Assessment for these individuals should be based on similar perspectives to those already discussed: intensity of use, degree of physical dependence on nicotine, motivation, self-efficacy, and analysis of previous quit attempts.

To assess the smoking intensity in smoking water pipe users, we must ask the smoker how many water pipes they smoke per week. Furthermore, determining CO levels in exhaled air and even cotinine levels in body fluids will be very useful for these smokers. The specific characteristics of these devices must be taken into account to accurately assess the smoking intensity of these users. It is important to assess whether smoking water pipe users also smoke conventional cigarettes; it is also important to consider the pattern of smoking these devices. Variations in these aspects can lead to significant differences in the parameters used to analyze smoking intensity in smoking water pipe users. Table 8S supplementary material shows the assessment of smoking intensity according to the number of water pipes smoked per week, the levels of CO in expired air and the blood cotinine levels. The figures for these last two parameters should be valued more than the number of smoking water pipes consumed.

To measure nicotine dependence, we used Lebanon Dependence Scale (LWDS-11). Lebanon Dependence Scale (LWDS-11) has been validated in different populations, making it the recommended nicotine dependence test for users of these products. However, it has not been validated in Spanish; therefore, the version presented here is simply a version translated by the authors of the manuscript. It is based on 11 items that help assess not only physical nicotine dependence, but also psychological dependence, type of reward, and craving. Table 9S supplementary material shows Lebanon Scale (LWDS-11) and its assessment [28].

VAS can be used to measure motivation and self-efficacy to quit smoking water pipes. The score assessment would be similar to that used for conventional cigarette users.

It is important to note that neither the cutoff points proposed in Table 8S supplementary material nor VAS have been validated for determining smoking intensity or for measuring the degree of motivation or self-efficacy to quit smoking water pipes. Therefore, these recommendations are not evidence-based, but we believe they should be very useful for daily clinical practice and that its joint use by the group of Spanish-speaking researchers will facilitate the fast validation of these scales in Spanish. The analysis of quit attempts in smoking water pipe users will follow the same guidelines as in conventional cigarette users.

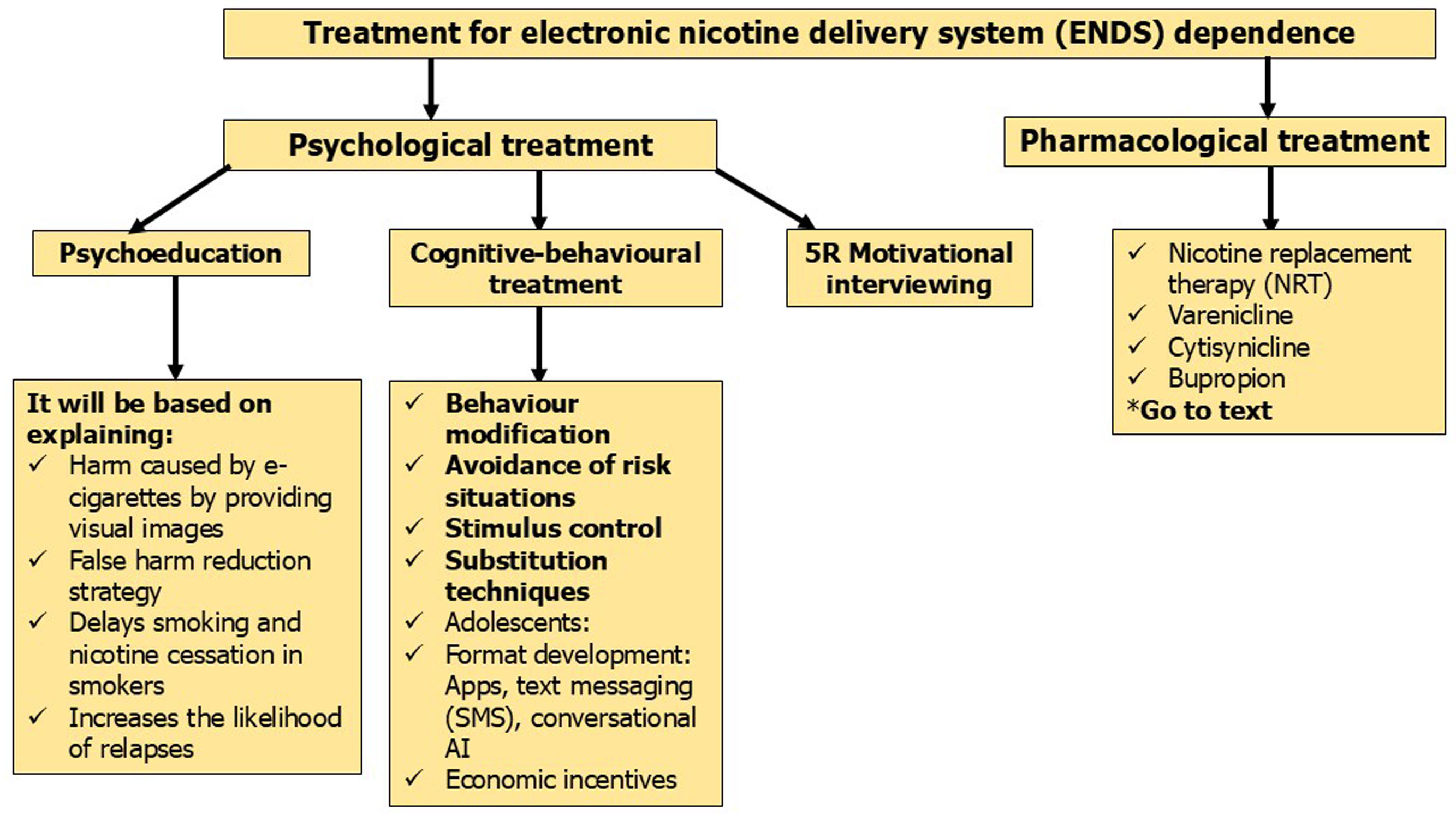

Treatment for users of new tobacco and nicotine productsTreatment for users of new tobacco and nicotine products is basically the same as for conventional cigarette smokers. That is, a combination of psychological counseling to combat the psychosocial dependence caused by these devices and pharmacological treatment to alleviate physical dependence on nicotine. Throughout this section, the specific characteristics of psychological counseling for each of these smokers will be discussed, and the results and conclusions of the few studies that have been conducted on the efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatment for users of these new devices will be presented.

Psychological counselingThe proposal for psychological counseling for consumers of new forms of tobacco and nicotine consumption is as follows:

PsychoeducationIt is essential to briefly, clearly, and concisely explain the risks of consuming tobacco or nicotine through any of these devices. It is highly recommended to accompany these explanations with visual images to reinforce them. It is also important to make it clear that quitting these forms of consumption is accompanied by significant health benefits [29–33].

Psychoeducation should also serve to debunk the myth of harm reduction. None of these devices (ENDS, tobacco heaters, and smoking water pipes) can reduce the harm associated with tobacco use. All of them are as harmful as conventional cigarette use [29–33].

Psychoeducation should clarify that using ENDS does not help people quit smoking. It is known that the use of these devices by young people and non-smoking adults serves as a gateway to using conventional cigarettes; and in adult smokers, it reduces their chances of quitting smoking and causes them to become dual smokers [9,29–33].

Psychoeducation is the treatment of choice for vapers or users of smoking water pipes or heated tobacco who show low motivation (less than 8 points on VAS) and high self-efficacy (8 or more points on VAS) to quit these devices. The effectiveness of psychoeducation is reduced in countries where there is a lack of legislation strictly regulating the sale, consumption, and advertising of these new devices [29–33].

Cognitive-behavioral therapy. (CBT)It is indicated for those who are motivated to quit any of these devices (8 or more points on VAS). CBT model should work on the following components: (1) increasing motivation to quit, (2) assessing the degree of dependence and evaluating the presence of withdrawal symptoms, (3) providing intense social support, (4) identifying triggers for use with functional behavioral analysis, (5) facilitating coping with cravings, (6) providing tools for managing negative emotions, and (7) helping to prevent relapse [34].

It is important to differentiate between psychological counseling for adults and adolescents. In this sense, technology-based smoking cessation interventions appear to have a more relevant role among young people aged 18–25. Psychological counseling requires a broader behavioral intervention for this type of use, increasing the duration and frequency of visits in any of the three formats: individualized, group, or telephone [35,36]. On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that for better communication with adolescents, the term “vaping” should always be used rather than “ENDS use.” Furthermore, it is more appropriate to refer to “devices that are harmful to health and dangerous” than “devices that are risky to use.” Another added problem in counseling adolescents is that they generally have a false perception of their ability to abandon these devices whenever they want. It is highly recommended to emphasize to them that they are addicted to their use and that they will have difficulties when they want to quit [37]. Offering rewards, both monetary and in the form of video games or other digital devices, to contribute to providing cotinine-free urine samples is advocated as a tool for CBT in adolescents. A review of 56 studies indicated these practices as very suitable for helping adolescents quit these devices [38]. A recent meta-analysis suggests that in one study, reducing nicotine concentration through devices may increase quit rates at six-month follow-up, although confidence interval data show no intervention effect and indicate high quit rates in the control arm (RR 3.38, 95% CI 0.43–26.30; 1 study with 17 participants) [10]. This meta-analysis shows two studies involving 4091 subjects, which analyzed the effectiveness of sending text messages associated with quit advice versus usual care in vapers aged 13–24 years. The results showed a low level of evidence (RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.19–1.47) [10]. The conclusions of this meta-analysis indicate low-certainty evidence for the effectiveness of text messaging or for the effectiveness of reducing nicotine levels through new devices in achieving cessation [10].

Cognitive-behavioral therapy for smoking water pipe users should take into account that these devices are used in the company of others. Therefore, it is highly desirable for this type of counseling to reach those who accompany the user during smoking [39,40]. However, there is low-certainty evidence regarding the effectiveness of behavioral support for smoking water pipe cessation [39,40].

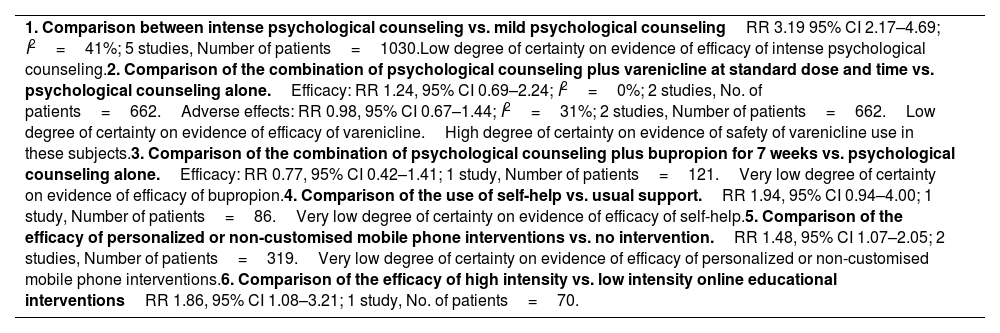

More trials with larger, well-designed samples are needed on behavioral and digital health interventions for smoking cessation in smoking water pipe users. A Cochrane review found 9 studies with 2841 participants, all adults, that analyzed interventions to help waterpipe users quit. Table 3 shows the results and conclusions of this meta-analysis [40].

Penn State E-cigarette dependence (PS-ECDI).

| 1. How many cigarettes (times) per day do you usually smoke (use your electronic cigarette?) (assume that one time consists of around 15 puffs or lasts around 10min) | 0–4: 05–9: 110–14: 215–19: 320–29: 4≥30: 5 |

| 2. On days that you can smoke (use your electronic cigarette) freely, how soon after you wake up do you smoke first cigarette of the day (first use your electronic cigarette)? | 0–5: 56–15: 416–30: 331–60: 261–120: 1≥120: 0 |

| 3. Do you sometimes awaken at night to have a cigarette (use your electronic cigarette) | Yes: 1No: 0 |

| 4. If yes, how many nights per week do you typically awaken to smoke? | 0–1 nights: 02–3 nights: 1≥4 nights: 2 |

| 5. Do you smoke (use an electronic cigarette) now because it is really hard to quit? | Yes: 1No: 0 |

| 6. Do you ever have strong cravings to smoke (use an electronic cigarette)? | Yes: 1No: 0 |

| 7. Over the past week, how strong have the urges to smoke (use an electronic cigarette) been? | None/Slight: 0Moderate/Strong: 1Very strong/Extremely strong: 2 |

| 8. Is it hard to keep from smoking (using an electronic cigarette) in places where you are not supposed to? | Yes: 1No: 0 |

| 9. Did you feel more irritable because you could not smoke (use an electronic cigarette)? | Yes: 1No: 0 |

| 10. Did you feel nervous, restless or anxious because you could not smoke (use an electronic cigarette)? | Yes: 1No: 0 |

Rating:

- 0–3=Not dependent.

- 4–8=Low degree of dependency.

- 9–12=Moderate degree of dependency.

- 13 or more=High degree of dependency.

This is a type of patient-centered counseling designed to help people explore and resolve ambivalence about behavior change. It is indicated for smokers with low motivation (less than 8 points on VAS) and low self-efficacy (less than 8 points on VAS). It is based on the 5 Rs model (relevance, risk, reward, resistance, and repetition). Empathy and understanding will be shown, the development of discrepancies between current behavior and goals or values important to users will be encouraged, and self-efficacy for change will be supported [33,35].

Motivational interviewing with adolescents should meet specific characteristics: it should begin by discussing the health risks of vaping and, after respectfully asking the young person about their interest in continuing this type of conversation, the young person's level of motivation to quit using these devices should be determined by showing them the VAS. After reviewing these results, the patient could be asked again why they gave such a low score. When the young person answers, it would be time to intervene to explain their false beliefs and try to reduce their resistance [41].

The characteristics of psychological counseling described in this section refer to those that should be carried out in the context of specialized healthcare for the treatment of psychological dependence due to these new forms of tobacco and nicotine consumption. However, it is worth noting here the minimum characteristics that psychological counseling for these patients should meet when provided by a non-specialized healthcare professional. These characteristics are: (a) asking all patients, regardless of age, about their use of new forms of tobacco and nicotine consumption; (b) including nicotine and tobacco prevention in all healthcare activities; (c) investigating the motivation for quitting these forms of use; and (d) providing information on the health risks and the availability of effective treatments. Pediatricians should not neglect this type of intervention for their patients [42].

Pharmacological treatmentThere is limited information on the efficacy and safety of pharmacological treatment for smoking water pipe and tobacco heated users. There is also limited information, although some studies are available, on ENDS. Four drugs have been shown to be effective and safe in helping smokers quit: nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), bupropion, varenicline, and cytisinicline [43]. Below, we discuss the results and conclusions of the main studies that have analyzed the efficacy and safety of these drugs for treating dependence caused by new tobacco and nicotine consumption devices.

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT)NRT consists of administering nicotine in decreasing doses and through routes other than tobacco use. This method counteracts withdrawal symptoms without creating dependence. Several studies, many of them with very small numbers of participants and poor methodology, have analyzed the efficacy and safety of NRT as a pharmacological treatment for ENDS dependence.

In 2016, Silver et al. described the case of a 24-year-old male who, after a year without smoking, began using e-cigarettes. After using them for 7 months, he considered quitting. The patient was given NRT in 14mg patches along with 4mg nicotine tablets daily, achieving complete abstinence after 12 months [44].

In 2021, Sikka et al. published a case series of ENDS users who wanted to quit vaping. Six patients who had used ENDS for at least 1 year were included in the study and followed for 12 months. None of them had previously used conventional cigarettes or attempted to quit using ENDS. All patients were administered 21mg patches daily for the first month, subsequently reducing to 14mg/day for the second month, and 7mg/day for the third month. In addition, all patients received advice via email or mobile phones, as well as monthly phone calls. All patients in this case series reduced their ENDS use, and four of them quit completely [45]. Following this same line of research, the group of Sahr et al. published a pilot study of three ENDS cessation methods in 2021 [46]. Three arms were established in the study: NRT+behavioral support, vaping taper+behavioral support, and self-quit as the control group. A total of 24 participants were included in the study. Data were collected prospectively over a period of six months. The primary variable was the number of participants who quit vaping and achieved nicotine freedom at 12 weeks and 6 months. The self-quit arm had the highest success rate with 77.8% at 12 weeks and 44.4% at 6 months. The vaping taper group showed favorable results in 75% at 12 weeks and 6 months. The NRT group achieved the lowest success rate with 42.9% at both time points [46].

Although a recent study of 586 ENDS users, which analyzed factors associated with successful quit attempts, found that NRT use was the only cessation method associated with a significant increase in the chances of success [47], to date, there are no protocolized studies on this topic. The paucity of studies, methodological deficiencies, and variability in results prevent valid conclusions from being drawn [47,48].

The conclusions of the most recent meta-analysis suggest that data on the efficacy of NRT use for quitting vaping are imprecise and inconclusive; the evidence for the efficacy of this medication for vaping treatment is of very low certainty (RR 2.57, 95% CI 0.29–22.93; 1 study, 16 participants) [10]. A recent study supports the usefulness of nicotine oral spray in controlling cravings among ENDS users during the process of quitting vaping [49].

We found no studies on NRT treatment for controlling dependence on heated tobacco or smoking water pipes. The efficacy of NRT as a smoking cessation medication could justify the effectiveness of this medication in controlling dependence on those forms of smoking, but studies to demonstrate this are needed.

VareniclineVarenicline is a partial agonist at α4β2 nicotinic receptors. Its use helps control cravings and reduce withdrawal symptoms in smokers who are quitting [43]. In 2019, Barkat et al. [50] described the case of a 53-year-old man who had quit smoking conventional cigarettes and then began using ENDS for 4 years. When he decided to quit vaping, he was prescribed behavioral therapy and varenicline at standard doses. He was followed for 6 months. He remained abstinent from vaping at 3 and 6 months [50].

In 2019, a cohort study was conducted in the United Kingdom with 204 dual smokers. 39% agreed to take varenicline to quit smoking and vaping. Those who used varenicline quit using conventional cigarettes in greater numbers than those who did not (17.5% vs. 4.8%; P=.006; [RR], 3.6; [CI], 1.4–9.0); a similar result was obtained for those who quit vaping (12.5% vs. 1.6%; P=.007; RR, 7.8; CI, 1.7–34.5); and for those who quit both forms of consumption (conventional cigarettes and ENDS), the data were as follows: 8.8% vs. 0.8%; P=.02; RR, 10.9; CI, 1.4–86.6. Users treated with varenicline reported less satisfaction with vaping (P=0.04) and significant reductions in e-cigarette use compared with non-users at 3 months (P<0.001) and 6 months (P<0.001) [51].

Recently, Caponnetto et al. published a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of varenicline at standard doses combined with psychological counseling in ENDS users who wanted to quit vaping. The results showed that varenicline was more effective than placebo in helping users quit vaping at 3 and 6 months of follow-up: 40.0% OR=2.67; 95% CI=[1.25–5.68], P=0.011; and 20.0% OR=2.52, 95% CI=[1.14–5.58], P=0.0224, respectively [52]. A study in young vapers aged 16–25 years confirmed the efficacy of varenicline over placebo in this group [53]. The conclusions of the latest meta-analysis indicate that there is a low level of evidence for the efficacy of varenicline in helping people quit vaping (RR 2.00, 95% CI 1.09–3.68; 1 study, 140 participants) [10].

Regarding smoking water pipe, one of the first studies conducted was Dogar et al. in Pakistan [54]. It was a double-blind, randomized, controlled study that included 510 smoking water pipe users, more than half of whom were also tobacco users, to receive two sessions of behavioral support plus varenicline for 12 weeks at standard doses or to receive the two sessions of behavioral support plus placebo. No statistically significant differences were found in timely abstinence between the varenicline group (12 of 253, 4.7%) versus the placebo group (11 of 257, 4.3%), RR=1.11, 95% CI, 0.50–2.47, P=0.8 [54].

Two meta-analyses have been conducted to determine the efficacy of varenicline for smoking water pipe cessation [39,40]. The most recent included a total of two studies involving 662 smoking water pipe users. The results comparing the efficacy of the combination of psychological counseling plus varenicline at a standard doses versus psychological counseling alone showed the following data: RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.69–2.24) and no significant adverse effects (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.67–1.44); this implies a low level of certainty regarding the evidence of varenicline's efficacy and a high level of certainty regarding the safety of varenicline use in these subjects (Table 4) [40].

Meta-analysis of efficacy and safety of treatments for waterpipe dependence.

| 1. Comparison between intense psychological counseling vs. mild psychological counselingRR 3.19 95% CI 2.17–4.69; I2=41%; 5 studies, Number of patients=1030.Low degree of certainty on evidence of efficacy of intense psychological counseling.2. Comparison of the combination of psychological counseling plus varenicline at standard dose and time vs. psychological counseling alone.Efficacy: RR 1.24, 95% CI 0.69–2.24; I2=0%; 2 studies, No. of patients=662.Adverse effects: RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.67–1.44; I2=31%; 2 studies, Number of patients=662.Low degree of certainty on evidence of efficacy of varenicline.High degree of certainty on evidence of safety of varenicline use in these subjects.3. Comparison of the combination of psychological counseling plus bupropion for 7 weeks vs. psychological counseling alone.Efficacy: RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.42–1.41; 1 study, Number of patients=121.Very low degree of certainty on evidence of efficacy of bupropion.4. Comparison of the use of self-help vs. usual support.RR 1.94, 95% CI 0.94–4.00; 1 study, Number of patients=86.Very low degree of certainty on evidence of efficacy of self-help.5. Comparison of the efficacy of personalized or non-customised mobile phone interventions vs. no intervention.RR 1.48, 95% CI 1.07–2.05; 2 studies, Number of patients=319.Very low degree of certainty on evidence of efficacy of personalized or non-customised mobile phone interventions.6. Comparison of the efficacy of high intensity vs. low intensity online educational interventionsRR 1.86, 95% CI 1.08–3.21; 1 study, No. of patients=70. |

There is no data on the efficacy of varenicline as an aid to quit using heated tobacco. The efficacy of this medication for treating smoking may justify its use in this type of smoker. However, studies are needed to confirm this.

BupropionBupropion is an antidepressant that acts as a norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It acts as a non-competitive antagonist at the nicotine receptor, thereby improving withdrawal symptoms [43]. Although it is effective for smoking cessation, there are currently no clinical studies or case reports that provide data to support its use in subjects wishing to quit vaping.

Its efficacy and safety in helping people quit using smoking water pipes was reviewed in a meta-analysis [40]. This article cites a study involving a total of 121 smoking water pipe users. The study compared the efficacy of a combination of psychological counseling plus bupropion for 7 weeks versus psychological counseling alone. The results showed no significant differences between the two treatments (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.42–1.41) (Table 4) [40].

There is no data on the efficacy of bupropion in helping people quit using heated tobacco. The efficacy of this medication in treating smoking cessation may justify its use in this type of smoker. However, studies are needed to confirm this.

CytisiniclineCytisinicline is a partial nicotinic receptor agonist that has been shown to be effective and safe for smoking cessation [43]. Continuous abstinence was analyzed with cytisinicline vs placebo in a clinical trial of 160 vapers from the ORCA cohort. Cytisinicline was administered at a dose of 3mg three times daily for 12 weeks. Continuous abstinence was observed in 31.8% of vapers in the cytisinicline group vs 15% in the placebo group at the end of treatment (odds ratio, 2.64; 95% CI, 1.06–7.10; P=.04). The results at 16 weeks of follow-up showed the following data: 23.4% in the active group vs. 13.2% in the placebo group (odds ratio, 2.00; 95% CI, 0.82–5.32; P=.15) [55].

The conclusions of the most recent meta-analysis suggest that the data on the efficacy of cytisinicline for vaping cessation are imprecise and inconclusive. No clinical trials using cytisinicline report data at six months or more of follow-up [10]. There is no data on the efficacy of cytisinicline treatment in users of heated tobacco and smoking water pipes.

In summary, there is data suggesting that NRT, varenicline, and cytisinicline may be effective in helping vapers quit. Although efficacy appears to be more evident with varenicline than with other drugs, robust and rigorous data to support this claim is still lacking [10,44–55]. Further studies with appropriate methodology and larger numbers of patients are needed to obtain clear scientific evidence.

On the other hand, regarding the efficacy of treatments for smoking water pipe users, the most compelling conclusions were reached by the latest meta-analysis: (a) low evidence of the efficacy of behavioral interventions for quitting these devices; (b) insufficient evidence on the efficacy of varenicline or bupropion in helping users of these devices; (c) large studies are needed to analyze the efficacy of electronic behavioral interventions; and (d) well-designed, controlled, personalized studies targeting special populations are needed: young people, pregnant women, dual smokers, etc. [39,40].

Currently, no studies are available that have analyzed the efficacy of treatments for heated tobacco users. Nevertheless, considering that heated tobacco use can be assimilated in all its characteristics to that of conventional cigarettes, it could be supposed that, given the efficacy and safety of these medications for treating conventional smoking, they would also be effective for heated tobacco use. However, this assertion must be supported by the results of well-designed and controlled scientific studies yet to be conducted.

Recommendations for treatment of vapersIt should be noted that the treatment indicated here is for users of ENDS only. Dual smokers should be treated like conventional cigarette smokers; taking into account that being a dual smoker entails, in addition to a greater risk of developing associated diseases, an increased level of physical and psychological dependence, which requires increasing the intensity of psychological counseling and pharmacological treatment [43,56].

Based on the limited scientific evidence available on this topic, we recommend that the type of treatment prescribed for vapers be based on the following variables: degree of motivation and self-efficacy to quit using these devices, and intensity and degree of dependence on them.

If vapers have low motivation and self-efficacy to quit, the treatment of choice will be motivational interviewing. For those with high self-efficacy and low motivation, psychoeducation is recommended. For patients with high motivation and low/high self-efficacy, the proposed treatment is a combination of psychological counseling and pharmacological treatment. In the latter case, psychological counseling should include psychoeducation and cognitive behavioral therapy. Regarding pharmacological treatment, the following drugs may be prescribed: varenicline, NRT, cytisinicline, or bupropion. For the use of one or the other, the following parameters will be assessed: level of efficacy and safety of the treatments, degree of dependence on e-cigarettes, and intensity of use. For smokers with a low or moderate level of dependence (13 or fewer points on PS-ECDI or fewer than 4 points on each item of EDS-4 scale) or low or moderate vaping intensity (19 or fewer times per day using ENDS, less than 4 or more hours of vaping per day, and less than 201ng/mL of cotinine in plasma), the following are recommended: varenicline and NRT as monotherapy, and cytisinicline. In smokers with a high degree of dependence (more than 13 points on PS-ECDI, or 4 or more points in each of the items on EDS-4) or high degree of vaping intensity (20 or more times per day in which an ENDS is used, 4 or more hours per day of use of this device and more than 200ng/mL of cotinine in plasma), the use of varenicline or combined NRT is recommended; in case of no response, the use of varenicline plus nicotine patches is recommended (Figs. 3 and 4).

Author contributionsAll authors have contributed to the preparation of this manuscript.

Ethical reviewThis manuscript was approved by the SEPAR Document Management Committee. It does not require approval by the Clinical Research Ethics Committees.

Funding sourcesThis study did not receive funding from public or private entities.

Conflict of interestCRC has received honoraria for speaking engagements, sponsored courses, and participation in clinical studies from Adamed, Aflofarm, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Chiesi, Novartis, J&J, Pfizer, and Teva.

CAJ-R has received honoraria for presentations, participation in clinical studies and consultancy from: Adamed, Aflofarm, Bial, Chiesi, GSK, Gebro Pharma, Kenvue, Neuraxpharm and Pfizer.

JAR reports grants and personal fees from Aflofarm, Adamed, GSK, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, Novartis AG, Menarini, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial from Astra-Zeneca, Grants and personal fees from, Gebro Pharma, personal fees from Sanofi-Regeneron, outside the submitted work.

JIG-O has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, Adamed, Boehringer, Esteve, Neuroxpharm and Pfizer.

IGU has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, Chiesi, Menarini and Pfizer.

AFG has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm.

EPP has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, Bial, Chiesi, FAES, Ferrer, Novartis y Pfizer.

RSC has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Astra -Zéneca, Bial, Boehringer, Chiesi, FAES, Ferrer, Gebro, GSK, Menarini, Novartis, Pfizer, Rovi y Teva.

The other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with respect to this document.