About 40 years after the first full length article was published on pulmonary diffusing capacity for nitric oxide (DLNO) – also called transfer capacity of the lung for nitric oxide, TLNO – the test remains underused in routine pulmonary function testing despite clear technical strengths and clinically relevant complementarity with DLCO. The modern single-breath approach emerged with the first full paper by Guénard et al., who demonstrated that simultaneous DLNO–DLCO could separate a membrane-weighted and a blood-weighted component of gas transfer [1], per the equation first published by Roughton and Forster [2]. Borland and Higenbottam operationalized a practical single-breath protocol [3], and, 28 years later, a European Respiratory Society (ERS) Task Force standardized inspired gas, breath-hold timing, sampling, and reporting [4]. Together these steps made DLNO ready for clinical use, yet acceptance has lagged. This editorial distills five challenges – and pragmatic solutions – to move DLNO from niche method to everyday practice.

Challenge 1 – A thin commercial ecosystem and regulatory inertiaDevices capable of simultaneous NO–CO measurements exist, but manufacturers are few and platforms differ in sensor technology (chemiluminescence, electrochemical, laser), response time, cross-sensitivities (humidity and CO2), calibration routines, gas mixtures, and calculation algorithms. These differences shift absolute values and complicate portability of reference equations across devices. Standardizing gas preparation, sampling, and computational steps; specifying minimum analyzer performance (rise time, drift, interference limits); and building software that can be updated as reference equations and models evolve are essential. In the United States, the absence of FDA clearance for NO–CO systems and limited clinician awareness have further concentrated DLNO as research tools only. A practical way forward is multi-site method-comparison trials that include device brand as a covariate, shared quality-assurance protocols, and regulatory-ready analytical validation packages. Laboratories should explicitly report device brand, analyzer type, software version, and breath-hold time (BHT) in manuscripts and clinical reports to improve comparability and accelerate harmonization.

Challenge 2 – Reference equations must account for altitude and genetic ancestryDiffusing capacity depends on alveolar volume, hemoglobin, and reaction-diffusion kinetics; it also varies across populations and environments. In Mexican Hispanics, habitual residence at ∼2240m increased DLNO, DLCO, and alveolar volume compared with lowlanders, and models that included altitude and population terms reduced error and misclassification relative to race-neutral models [5]. Complementary work argued specifically for race-specific DLNO equations to reduce false positives and false negatives in clinical practice [6]. These findings contradict the recent American Thoracic Society statement advocating race-neutral reference equations for pulmonary function test interpretation [7], a recommendation issued without supporting evidence or a transparent evidentiary process. Where device-and timing-specific equations for majority populations already exist [5,8], laboratories should report z-scores that incorporate altitude and ancestry when they measurably improve calibration, and consider parallel reporting of race-neutral values when available. Practically, this means listing the exact reference set and device used, stating the altitude (or barometric pressure) at testing, and indicating whether ancestry-specific or race-neutral z-scores were used to define the lower limit of normal, along with any shift in classification that results from the choice.

Challenge 3 – Build global DLNO reference equationsThe field needs multi-center, multi-ancestry DLNO–DLCO datasets that explicitly encode device brand, altitude, and breath-hold time. A standing consortium could harmonize protocols, pool raw data, and generate globally applicable equations with clear device/timing annotations. Current resources include validated sets for Mexican Hispanic [5], Black adults [6], and White populations [8], but larger samples are required in Blacks [6] and broader ancestry representation are also required to minimize misclassification and facilitate international adoption. A minimal data standard should include triplicate DLNO–DLCO maneuvers with 5–6s BHT, accepted quality criteria, hemoglobin values, body size, age and sex, and reporting of spirometry and lung volumes to anchor interpretation. When feasible, testing sites should report diffusing capacity using two different breath-hold times (approximately 5 seconds and 10 seconds) to facilitate assessment of ventilation heterogeneity effects.

Challenge 4 – Two gases are better than oneBeyond mechanism, adding DLNO to DLCO materially improves case detection in several contexts. An individual-participant data (IPD) meta-analysis in heart failure found that the double-diffusion approach enhanced classification compared with DLCO alone [9]. In post-COVID cohorts, another IPD meta-analyses demonstrated that summed DLNO+DLCO z-score outperformed DLCO alone for identifying prior disease, improving both Matthews correlation and net reclassification [10]. In a Further IPD meta-analysis, hierarchical partitioning showed unique contributions from FEV1z-scores (R2=0.35)>DLNO z-scores (R2=0.21)>TLC z-scores (R2=0.11), totalling McFadden's R2=0.66 [11]. DLCO z-scores did not add any further useful information to the model. Also, category-free reclassification and Youden-threshold analyses showed small but favourable gains; the case–control risk gap improved by up to ∼5% when adding DLNO to a DLCO-based model [11]. The practical implication is simple: whenever a DLCO test is clinically indicated and equipment is available, measure DLNO in the same maneuver and report both values – and their ratio – together. Reports should include brief, mechanism-aware comments: e.g., disproportionately low DLNO with relatively preserved DLCO suggests a membrane/surface-path process; disproportionately low DLCO relative to DLNO suggests a blood-volume/hematocrit limitation or mixed pathology when both are reduced.

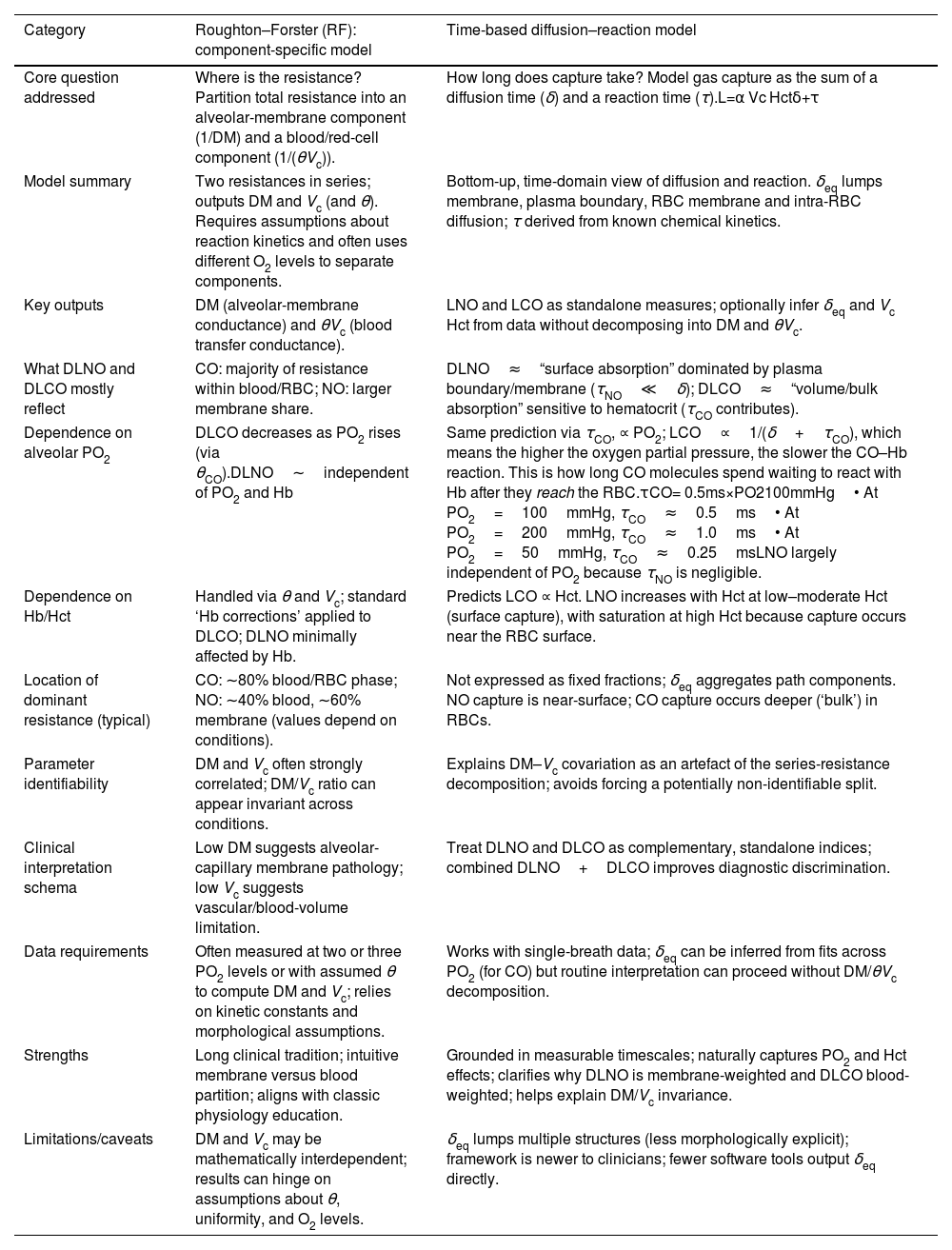

Challenge 5 – What DLNO means: reconciling component-splitting with time-based kineticsClinicians now encounter two ways to interpret diffusing capacity (Table 1). The classic Roughton–Forster (RF) framework treats total resistance as two serial terms – membrane (1/DM) and blood (1/(θVc)) – and has spurred back-calculations of DM and Vc from paired DLNO–DLCO [2]. A time-based diffusion–reaction framework instead derives uptake from first principles as the sum of an equivalent diffusion time (δeq) and a reaction time (τ) [12]. Because τNO is orders of magnitude smaller than δeq, DLNO behaves as surface absorption dominated by the membrane–plasma path and accessible RBC surface, whereas DLCO behaves as volume absorption that scales with hematocrit and engaged red blood cell (RBC) volume [12,13]. Importantly, exact solutions and 3-D models show that RBC peripheries are not equi-concentration surfaces, and diffusion times in series do not add, so extrapolating 1/DLCO versus PO2 to a unique “DMCO” is biased [14,15]. In reports, it is safer to present DLNO, DLCO, alveolar volume (VA), and the DLNO/DLCO ratio as observables and to flag any DM–Vc values as model-dependent. This approach preserves familiar language while aligning interpretation with physical constraints.

Two different frameworks for explaining DLCO and DLNO.

| Category | Roughton–Forster (RF): component-specific model | Time-based diffusion–reaction model |

|---|---|---|

| Core question addressed | Where is the resistance? Partition total resistance into an alveolar-membrane component (1/DM) and a blood/red-cell component (1/(θVc)). | How long does capture take? Model gas capture as the sum of a diffusion time (δ) and a reaction time (τ).L=α Vc Hctδ+τ |

| Model summary | Two resistances in series; outputs DM and Vc (and θ). Requires assumptions about reaction kinetics and often uses different O2 levels to separate components. | Bottom-up, time-domain view of diffusion and reaction. δeq lumps membrane, plasma boundary, RBC membrane and intra-RBC diffusion; τ derived from known chemical kinetics. |

| Key outputs | DM (alveolar-membrane conductance) and θVc (blood transfer conductance). | LNO and LCO as standalone measures; optionally infer δeq and Vc Hct from data without decomposing into DM and θVc. |

| What DLNO and DLCO mostly reflect | CO: majority of resistance within blood/RBC; NO: larger membrane share. | DLNO≈“surface absorption” dominated by plasma boundary/membrane (τNO≪δ); DLCO≈“volume/bulk absorption” sensitive to hematocrit (τCO contributes). |

| Dependence on alveolar PO2 | DLCO decreases as PO2 rises (via θCO).DLNO∼independent of PO2 and Hb | Same prediction via τCO, ∝ PO2; LCO∝1/(δ+τCO), which means the higher the oxygen partial pressure, the slower the CO–Hb reaction. This is how long CO molecules spend waiting to react with Hb after they reach the RBC.τCO= 0.5ms×PO2100mmHg• At PO2=100mmHg, τCO≈0.5ms• At PO2=200mmHg, τCO≈1.0ms• At PO2=50mmHg, τCO≈0.25msLNO largely independent of PO2 because τNO is negligible. |

| Dependence on Hb/Hct | Handled via θ and Vc; standard ‘Hb corrections’ applied to DLCO; DLNO minimally affected by Hb. | Predicts LCO ∝ Hct. LNO increases with Hct at low–moderate Hct (surface capture), with saturation at high Hct because capture occurs near the RBC surface. |

| Location of dominant resistance (typical) | CO: ∼80% blood/RBC phase; NO: ∼40% blood, ∼60% membrane (values depend on conditions). | Not expressed as fixed fractions; δeq aggregates path components. NO capture is near-surface; CO capture occurs deeper (‘bulk’) in RBCs. |

| Parameter identifiability | DM and Vc often strongly correlated; DM/Vc ratio can appear invariant across conditions. | Explains DM–Vc covariation as an artefact of the series-resistance decomposition; avoids forcing a potentially non-identifiable split. |

| Clinical interpretation schema | Low DM suggests alveolar-capillary membrane pathology; low Vc suggests vascular/blood-volume limitation. | Treat DLNO and DLCO as complementary, standalone indices; combined DLNO+DLCO improves diagnostic discrimination. |

| Data requirements | Often measured at two or three PO2 levels or with assumed θ to compute DM and Vc; relies on kinetic constants and morphological assumptions. | Works with single-breath data; δeq can be inferred from fits across PO2 (for CO) but routine interpretation can proceed without DM/θVc decomposition. |

| Strengths | Long clinical tradition; intuitive membrane versus blood partition; aligns with classic physiology education. | Grounded in measurable timescales; naturally captures PO2 and Hct effects; clarifies why DLNO is membrane-weighted and DLCO blood-weighted; helps explain DM/Vc invariance. |

| Limitations/caveats | DM and Vc may be mathematically interdependent; results can hinge on assumptions about θ, uniformity, and O2 levels. | δeq lumps multiple structures (less morphologically explicit); framework is newer to clinicians; fewer software tools output δeq directly. |

Abbreviations: Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit. Lung diffusing capacity for the gas CO or NO expressed as LCO or LNO. Notice “DL” is not used to avoid confusion with the Roughton–Forster (RF model) and to emphasize that diffusing capacity comes from timing. The “L” is derived from physics (δ+τ) rather than RF decomposition. α, gas solubility/partition coefficient; Vc, pulmonary capillary blood volume; Hct, hematocrit; δ, equivalent diffusion time; τ, reaction time with hemoglobin.

First, align technology: agree on minimum analyzer performance, require routine calibration checks for electrochemical NO sensors, publish cross-device transfer functions, and encourage shared biological controls. Second, lock in reference modeling: maintain device- and timing-specific equations, include altitude explicitly, and report ancestry-aware and race-neutral z-scores side-by-side where each adds value [5–8]. Third, refine interpretation: report DLNO and DLCO with their ratio and, when feasible, use two breath-hold times to probe heterogeneity [12–15]. Fourth, coordinated regulatory submissions backed by multi-center trials must be pursued so laboratories can adopt DLNO as readily as DLCO [10,11].

ConclusionDLNO began as a technically elegant measurement and is now a clinically useful companion to DLCO. Its broader adoption hinges on a healthy device ecosystem, ancestry- and altitude-specific reference equations, clear interpretive language that acknowledges model dependence, and well-designed clinical validation. None of these barriers are insurmountable. With deliberate alignment across manufacturers, laboratories, and professional societies, DLNO can move from promising to routine within the next few years.

Conflict of interestThis author does not have any financial or personal relationships that could constitute a conflict of interest.