Bench testing plays a crucial role in respiratory medicine for evaluating non-invasive ventilation (NIV) devices. It allows detailed assessment of ventilator performance, patient–ventilator interaction, and physiological responses without the risks of patient trials. With NIV increasingly used across patient groups and ventilator technology evolving, bench testing has become more important.

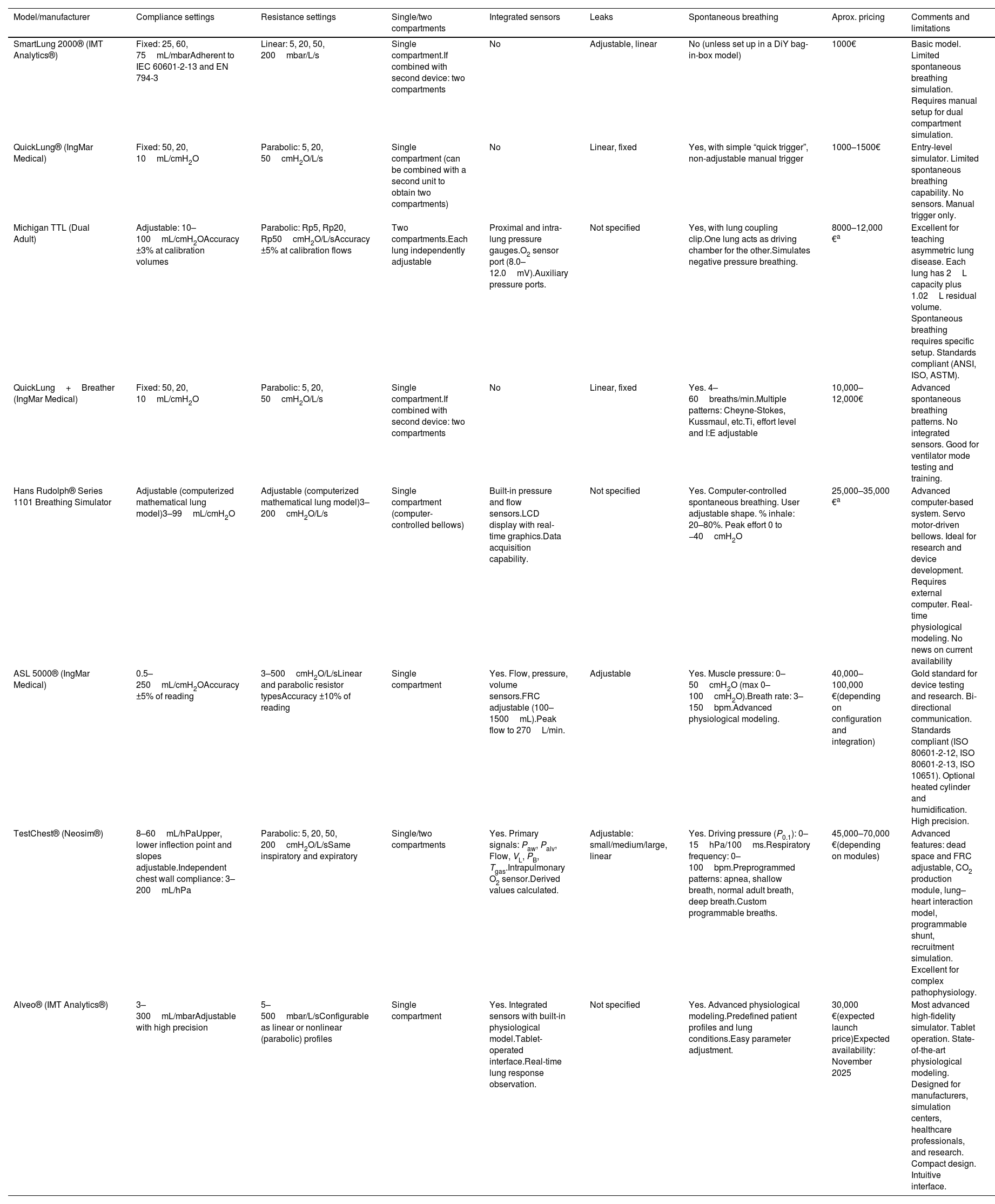

Simulation devices for bench testing range from simple passive lung simulators like SmartLung® and QuickLung® that are affordable but limited in replicating spontaneous breathing, to mid-level models offering some adjustment of breathing effort (i.e., Michigan testLung®). Advanced active simulators like the ASL 5000 (IngMar Medical) and newer models such as TestChest® (Neosys) and Alveo® (IMT Analytics) provide complex and realistic respiratory mechanics, accurately mimicking muscle forces for detailed device evaluation. Table 1 summarizes current available simulators.

Most common available lung simulators. From basic to top-end models.

| Model/manufacturer | Compliance settings | Resistance settings | Single/two compartments | Integrated sensors | Leaks | Spontaneous breathing | Aprox. pricing | Comments and limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SmartLung 2000® (IMT Analytics®) | Fixed: 25, 60, 75mL/mbarAdherent to IEC 60601-2-13 and EN 794-3 | Linear: 5, 20, 50, 200mbar/L/s | Single compartment.If combined with second device: two compartments | No | Adjustable, linear | No (unless set up in a DiY bag-in-box model) | 1000€ | Basic model. Limited spontaneous breathing simulation. Requires manual setup for dual compartment simulation. |

| QuickLung® (IngMar Medical) | Fixed: 50, 20, 10mL/cmH2O | Parabolic: 5, 20, 50cmH2O/L/s | Single compartment (can be combined with a second unit to obtain two compartments) | No | Linear, fixed | Yes, with simple “quick trigger”, non-adjustable manual trigger | 1000–1500€ | Entry-level simulator. Limited spontaneous breathing capability. No sensors. Manual trigger only. |

| Michigan TTL (Dual Adult) | Adjustable: 10–100mL/cmH2OAccuracy ±3% at calibration volumes | Parabolic: Rp5, Rp20, Rp50cmH2O/L/sAccuracy ±5% at calibration flows | Two compartments.Each lung independently adjustable | Proximal and intra-lung pressure gauges.O2 sensor port (8.0–12.0mV).Auxiliary pressure ports. | Not specified | Yes, with lung coupling clip.One lung acts as driving chamber for the other.Simulates negative pressure breathing. | 8000–12,000 €a | Excellent for teaching asymmetric lung disease. Each lung has 2L capacity plus 1.02L residual volume. Spontaneous breathing requires specific setup. Standards compliant (ANSI, ISO, ASTM). |

| QuickLung+Breather (IngMar Medical) | Fixed: 50, 20, 10mL/cmH2O | Parabolic: 5, 20, 50cmH2O/L/s | Single compartment.If combined with second device: two compartments | No | Linear, fixed | Yes. 4–60breaths/min.Multiple patterns: Cheyne-Stokes, Kussmaul, etc.Ti, effort level and I:E adjustable | 10,000–12,000€ | Advanced spontaneous breathing patterns. No integrated sensors. Good for ventilator mode testing and training. |

| Hans Rudolph® Series 1101 Breathing Simulator | Adjustable (computerized mathematical lung model)3–99mL/cmH2O | Adjustable (computerized mathematical lung model)3–200cmH2O/L/s | Single compartment (computer-controlled bellows) | Built-in pressure and flow sensors.LCD display with real-time graphics.Data acquisition capability. | Not specified | Yes. Computer-controlled spontaneous breathing. User adjustable shape. % inhale: 20–80%. Peak effort 0 to −40cmH2O | 25,000–35,000 €a | Advanced computer-based system. Servo motor-driven bellows. Ideal for research and device development. Requires external computer. Real-time physiological modeling. No news on current availability |

| ASL 5000® (IngMar Medical) | 0.5–250mL/cmH2OAccuracy ±5% of reading | 3–500cmH2O/L/sLinear and parabolic resistor typesAccuracy ±10% of reading | Single compartment | Yes. Flow, pressure, volume sensors.FRC adjustable (100–1500mL).Peak flow to 270L/min. | Adjustable | Yes. Muscle pressure: 0–50cmH2O (max 0–100cmH2O).Breath rate: 3–150bpm.Advanced physiological modeling. | 40,000–100,000 €(depending on configuration and integration) | Gold standard for device testing and research. Bi-directional communication. Standards compliant (ISO 80601-2-12, ISO 80601-2-13, ISO 10651). Optional heated cylinder and humidification. High precision. |

| TestChest® (Neosim®) | 8–60mL/hPaUpper, lower inflection point and slopes adjustable.Independent chest wall compliance: 3–200mL/hPa | Parabolic: 5, 20, 50, 200cmH2O/L/sSame inspiratory and expiratory | Single/two compartments | Yes. Primary signals: Paw, Palv, Flow, VL, PB, Tgas.Intrapulmonary O2 sensor.Derived values calculated. | Adjustable: small/medium/large, linear | Yes. Driving pressure (P0.1): 0–15hPa/100ms.Respiratory frequency: 0–100bpm.Preprogrammed patterns: apnea, shallow breath, normal adult breath, deep breath.Custom programmable breaths. | 45,000–70,000 €(depending on modules) | Advanced features: dead space and FRC adjustable, CO2 production module, lung–heart interaction model, programmable shunt, recruitment simulation. Excellent for complex pathophysiology. |

| Alveo® (IMT Analytics®) | 3–300mL/mbarAdjustable with high precision | 5–500mbar/L/sConfigurable as linear or nonlinear (parabolic) profiles | Single compartment | Yes. Integrated sensors with built-in physiological model.Tablet-operated interface.Real-time lung response observation. | Not specified | Yes. Advanced physiological modeling.Predefined patient profiles and lung conditions.Easy parameter adjustment. | 30,000 €(expected launch price)Expected availability: November 2025 | Most advanced high-fidelity simulator. Tablet operation. State-of-the-art physiological modeling. Designed for manufacturers, simulation centers, healthcare professionals, and research. Compact design. Intuitive interface. |

Abbreviations: bpm: breaths per minute; cmH2O: centimeters of water (pressure unit); CO2: carbon dioxide; DiY: do-it-yourself; FRC: functional residual capacity; hPa: hectopascal (1hPa=1mbar=1.02cmH2O); I:E: inspiratory:expiratory ratio; IEC: International Electrotechnical Commission; L: liter; L/s: liters per second; mbar: millibar (pressure unit); mL: milliliter; O2: oxygen; Palv: alveolar pressure; Paw: airway pressure; PB: ambient (barometric) pressure; P0.1: airway occlusion pressure at 0.1s; Rp: parabolic resistance; Tgas: gas temperature; Ti: inspiratory time; TTL: training and test lung; VL: lung volume.

Pricing based on recent quotations requested by the author, manufacturer webpage prices, or estimates from multiple web sources when clear pricing was unavailable. Prices are approximate and subject to change.

Standards compliance: Several simulators meet international standards including IEC 60601-2-13, EN 794-3, ISO 80601-2-12, ISO 80601-2-13, ISO 10651, ANSI Z79.7, and ASTM F 1100-90.

Calibration: Annual calibration recommended for research/engineering applications; biannual calibration may be sufficient for educational use.

Educational manikins add anatomical realism and allow for testing interfaces and upper airway behaviour. Recent trends include 3D-printed head models based on actual patient imaging for more realistic simulations [1].

These testing systems can simulate a variety of breathing patterns including normal, obstructive, and restrictive profiles. They allow control over parameters like air leakage, respiratory rate, and pressure support, enabling detailed ventilator benchmarking. Setups may include external instrumentation to measure airflow, pressures, leaks, etc, or rely in internal sensors of the advanced lung simulators.

Despite many bench studies since the early 2000s, protocols and outcome measures still vary between labs [2]. While research has expanded to include ventilator comparisons, interface testing, and clinical scenarios, more consistency in methods is needed for stronger clinical application.

PRO: the case for bench testingWhen physicians prescribed a drug, they assume that the drug will have the efficacy demonstrated in clinical trials. They know common side effects and can explain to their patients why this drug will have such effect on their disease. But drugs are drugs, they have their chemically active compound that is always the same and their absorption body need to be stable. Indeed, drugs need to have stable pharmacokinetics. To illustrate that impact, switching from immediate release to long-term release drugs requires a medical prescription. For drugs, the only variability comes from the patient (who can have one cytochrome or another, who can have other drugs that creates interactions…). One may argue that NIV is the same: the active chemical compound is just air that is pressured into the lungs. It may be true. But then, the way that the drug is delivered, i.e. the pharmacokinetics of NIV should be stable. As each NIV manufacturer has developed its own turbine, its own algorithm, each NIV has a different pharmacokinetics. Hence, in the field of NIV, when we decide to administer a drug named NIV, we have variability coming from the patient (as any regular drugs) but we have another source of variability different NIV-pharmacokinetics. Things get even more complicated when no data is needed to issue a NIV ventilator on the market and make it ready to use in patients. Therefore, physicians have many drugs (NIV-ventilators) with different pharmacokinetics (that they do not know in most cases). As NIV is delivered in frails patients, as NIV is delivered to a small number of patients (as compared to sleep apnoea), and as patients requiring NIV have different respiratory mechanics, it is impossible to assess all NIV-pharmacokinetics in humans. However, knowing pharmacokinetics is essential, the only segue is to have data from bench tests. Bench testing excels in delivering safety and efficiency, enabling respiratory researchers and device manufacturers to examine ventilator responses to any scenarios, leaks, and asynchrony without jeopardizing patient safety. The laboratory environment facilitates rapid data gathering and robust comparative analysis at a fraction of the cost and logistical complexity of patient trials. Researchers gain deeper physiological insight, with precise control and measurement of parameters such as compliance, resistance, and flow that would be challenging to manipulate bedside. Standardized setups allow objective device comparisons, fostering innovation and raising industry standards. Regulatory bodies and clinicians alike benefit from quantitative, reproducible metrics, supporting evidence-based choices and safer clinical deployments.

Bench testing has already shown its clinical relevance during the COVID pandemic and other crisis in the field of NIV [3–5]. It may be argued that it does not replace clinical evaluation in humans and that is true. However, it is also a necessary step to ensure adequate behavior of the ventilator. Indeed, bench tests should be considered as a pre-clinical model to assess ventilators. This is how the industry is developing their ventilators. Nonetheless, these pre-clinical assessments need to be open and repeated in independent laboratories to ensure data quality. To bridge the gap with real-life assessments, bench test also needs to progress and validate their findings using real-life data [6–8].

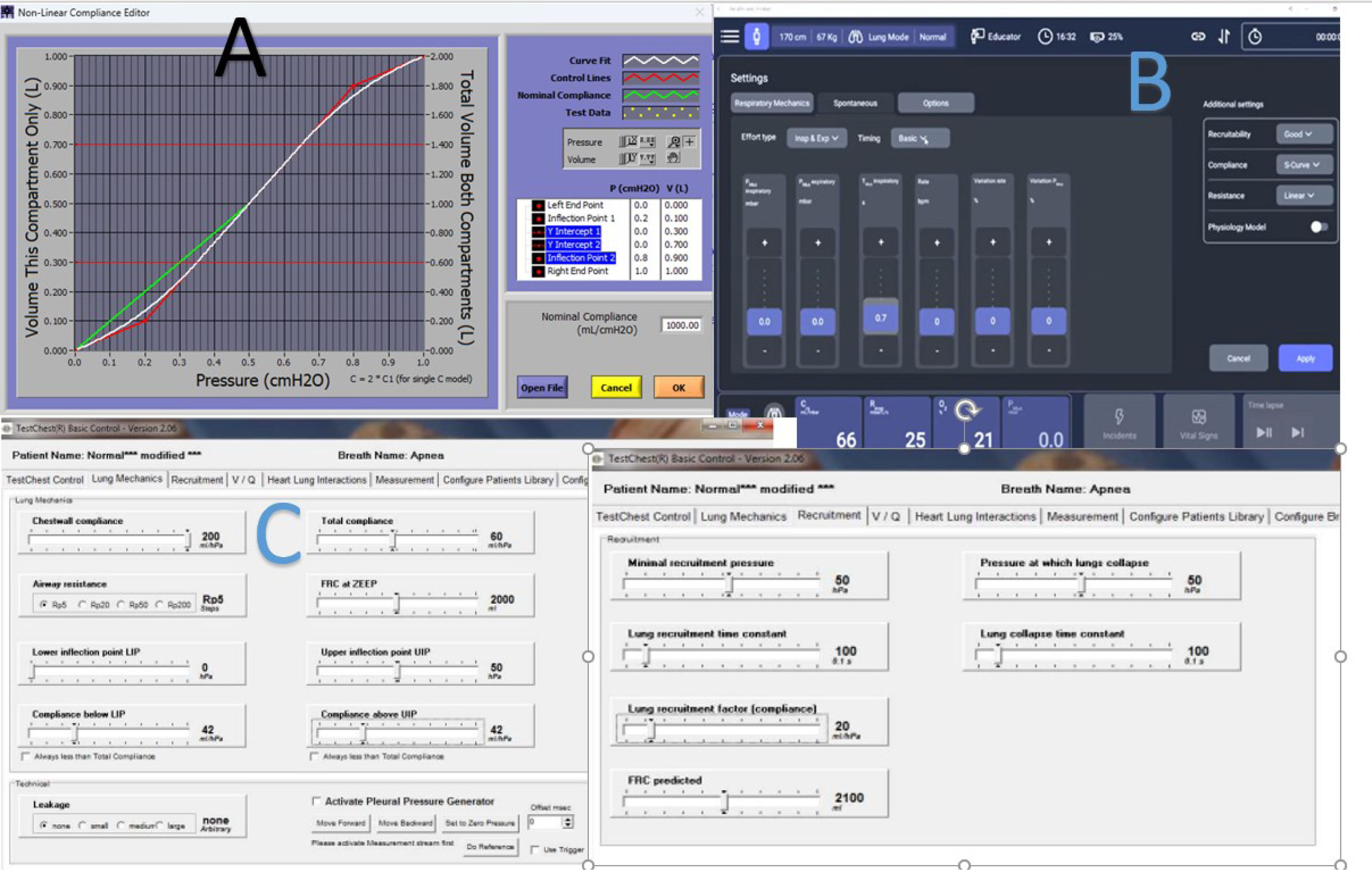

CON: the limits of simulationBench testing of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) devices is important but limited by significant variability in methods, making comparisons challenging. Different lung simulators vary in performance, and experimental setups differ in circuit configuration, environmental conditions (e.g., ATPS vs. BTPS), and signal measurement techniques. Analytical methods also lack standardization, with metrics like PTAP, PTP300, and PTP500 varying in calculation methods and components included, causing inconsistent reporting [2]. Statistical analyses differ, for example, in comparing median values versus individual breaths, impacting interpretation of ventilator performance. Bench models often fail to replicate complex patient physiology accurately, especially in simulating air leaks that are typically represented by simple valves (“proportional” leaks) rather than reflecting non-proportional, realistic leaks which affect ventilator synchrony [9]. Attempts to mimic real-life conditions face trade-offs between technical accuracy and physiological realism, limiting the predictive value of bench testing. The linearity of conventional lung models represents perhaps the most significant limitation of current bench testing approaches. Moreover, single or dual compartment models may not reflect the heterogenicity of sick lungs. Thus, the response of the ventilator may vary in the real patient in a non-predictable way. Even more, changes in compliance at different lung capacities may be challenging to be reflected by current simulators [10]. Only the more advanced, digitally controlled simulators may offer some capabilities to modify the pressure–volume relationship (hysteresis and volume-dependent compliance) as reflected in Fig. 1. Also, resistance may be challenging when considering it in a linear or in a parabolic way.

Pressure–volume curve tuning capabilities in three lung simulators. Interfaces for the most advanced lung simulators, showing capabilities of nonlinear compliance. (A) ASL5000® (IngMar Medical®) allows for settings of the whole compliance, and upper and lower inflection point, and differentiates inspiratory and expiratory resistance. (B) Alveo (IMT Analytics) in a similar way allows for upper and lower inflection points. (C) TestChest offers a more complex parameter settings regarding compliance, but only allows for global resistance setting.

Upper airway dynamics during NIV remain poorly replicated in bench setups. The interaction between positive pressure and compliant upper airway structures – particularly during sleep – significantly impacts NIV efficacy. Most bench models employ rigid conduits that fail to mimic physiological airway collapse or the complex nasopharyngeal flow dynamics. Glottic reflex is rarely simulated due to technical challenges. This limitation is especially relevant when evaluating triggers and cycling, as upper airway resistance substantially alters work of breathing and patient–ventilator synchrony. Studies employing Starling resistors to mimic upper airway collapse fail to explain laryngeal reactivity [11] and there is significant heterogeneity in resistor design across studies.

When evaluating technologies such as forced oscillation, which is incorporated in some ventilators and AutoPAP devices to automatically adjust expiratory pressure or CPAP levels, it should be acknowledged that the resulting responses may not be physiological [1]. This occurs because the underlying algorithms are designed to assess the “absorption” of pressure pulses by lung tissue rather than their reflection from a rigid surface, such as a lung simulator piston. Moreover, these discrepancies may be further amplified when comparing simulators based on different mechanical principles, such as rubber bellows, piston-driven, or other designs, as algorithms are designed to evaluate the “absorption” of pressure pulses by lung tissue, rather than impacting in a metal surface such as the lung simulator piston [12]. The differences between simulators introduce uncertainty regarding the reproducibility of published results (Table 1, current features of marketed simulators).

Finally, most bench studies evaluate ventilators under conditions that poorly represent the clinical scenarios for which the devices are intended. Few studies incorporate simulated patient efforts that accurately reflect the respiratory drive, timing, and variability seen in acute respiratory failure. While there has been some work in the field of appraising realistic effort patterns [13], most of the trials employ pure sinusoidal patterns (in best case when they mentioned it [14]).

The disconnect between bench testing and patient outcomes represents perhaps the most critical limitation of this approach. While bench studies can identify technical differences between devices, they cannot predict how these differences will translate into clinical efficacy. Usually patients under NIV are not sedated, may be awake or sleep, anxious or relaxed, with muscular impairment or fighting the ventilator, and successful NIV depends not only on technical performance but also on patient comfort, tolerance, and cooperation-factors that bench testing cannot adequately assess.

While bench testing provides valuable preliminary data on device performance, its findings must be interpreted cautiously within the context of these substantial limitations. The path from bench to bedside remains fraught with complexities that simplified mechanical models cannot address, necessitating robust clinical validation of any insights derived from bench testing methodologies. Some papers where this bench-to-bedside is developed can serve as a way to go for future trends [7,8].

Future trends: beyond the benchThe frontier of simulation is rapidly advancing. High-flow therapy is being integrated into bench platforms to reflect clinical trends and complex humidity-flow-oxygen dynamics [15]. Upper airway simulation, leveraging 3D-printing and fluid dynamics, better captures mask fit and dead space effects, such as rebreathing. Mathematical models and computational simulations incorporate real-world variability and non-linear respiratory mechanics. Digital twins promise patient-specific virtual testing, potentially bridging the gap between technical evaluation and individualized therapy. AI-driven analysis, biomimetic modeling, and smart sensor integration herald a new era of automated, physiologically relevant, and comprehensive simulation, though with their own demands for validation and standardization. Virtual reality and IoT training environments will embed bench realism in frontline education, forging stronger feedback loops between simulation and patient experience.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processAI tools (DeepL and Copilot) have been used to improve the English writing of the manuscript, but no generative AI was used without supervision to produce content.

Conflict of interestsJavier Sayas Catalán reports grants from Menarini and Philips, consultancy fees from Philips Respironics and ResMed.- Honoraria for lectures from Philips Respironics, support for attending meetings from Nippon Gases.

Maxime Patout reports grants from Fisher & Paykel, ResMed and Asten Santé, consultancy fees from Philips Respironics, Air Liquide Medical, ResMed, Asten Santé and GSK, payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, manuscript writing or educational events from Philips Respironics, Asten Santé, ResMed, Air Liquide Medical, SOS Oxygène, Antadir, Chiesi, Jazz Pharmaceutical, Loewenstein, Fisher & Paykel, Bastide Medical, Orkyn and Elivie, support for attending meetings from Asten Santé and Vitalaire, participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board with ResMed, Philips Respironics and Asten Santé, stock (or stock options) with Kernel Biomedical, and receipt of equipment, materials, drugs, medical writing, gifts or other services from Philips Respironics, ResMed and Fisher & Paykel.