The objective of the present study was to validate the Spanish version of the SAQLI, which is a health-related quality of life (HRQL) questionnaire specific for sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (SAHS), and to assess its sensitivity to change.

Material and methodsA multicenter study performed in a group of patients with SAHS (apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] ≥5) who had been referred to the centers’ Sleep Units. All patients completed the following questionnaires: SF-36, FOSQ, SAQLI and Epworth scale. The psychometric properties (internal consistency, construct validity, concurrent validity, predictive value, repeatability and responsiveness to change) of the SAQLI were assessed (four domains: daily function, social interactions, emotional function and symptoms; an optional fifth domain is treatment-related symptoms).

ResultsOne hundred sixty-two patients were included for study (mean age: 58±12; Epworth: 10±4; BMI: 33±5.9kgm−2; AHI: 37±15h−1). The factorial analysis showed a construct of four factors with similar distribution to the original questionnaire domains. Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha between 0.78 and 0.82 for the different domains), concurrent validity for SF-36, Epworth scale and FOSQ, and test–retest reliability were appropriate. The predictive validity of the questionnaire showed no significant correlations with the severity of SAHS. SAQLI showed good sensitivity to change in all the domains of the questionnaire (P<.01).

ConclusionsThe Spanish version of the SAQLI is a valid HRQL measurement with appropriate psychometric properties for use in patients with SAHS and it is sensitive to change.

El objetivo del presente estudio fue validar la versión española del Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI), cuestionario de calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) específico para el síndrome de apneas-hipopneas del sueño (SAHS), y evaluar su sensibilidad al cambio.

Material y métodosEstudio multicéntrico en un grupo de pacientes diagnosticados de SAHS (índice de apnea/hipopnea [IAH] ≥5) enviados a las unidades de sueño. En todos los pacientes se administraron los cuestionarios: SF-36, FOSQ, SAQLI y test de Epworth. Se evaluaron las propiedades psicométricas (consistencia interna, validez de constructo, validez concurrente, validez predictora, fiabilidad test–retest y sensibilidad al cambio) del cuestionario SAQLI (4 dominios: funcionamiento diario, interacciones sociales, funcionamiento emocional y síntomas; dispone de un quinto opcional: síntomas relacionados con el tratamiento).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 162 pacientes (media de edad: 58±12 años; Epworth: 10±4; IMC: 33±5,9kgm−2; IAH: 37±15h−1). El análisis factorial mostró un constructo de 4 factores, distribuidos de manera similar a los dominios del cuestionario original. La consistencia interna (alfa de Cronbach entre 0,78 y 0,82 para los distintos dominios), la validez concurrente con respecto al SF-36, Epworth y FOSQ, así como la fiabilidad test–retest, fueron adecuadas. La validez predictora del cuestionario no mostró correlaciones significativas por gravedad de SAHS. El SAQLI mostró una buena sensibilidad al cambio en todos los dominios que componen el cuestionario (p<0,01).

ConclusionesLa versión española del SAQLI presenta características psicométricas adecuadas para su utilización en pacientes con SAHS y es sensible al cambio.

Sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (SAHS) is a very prevalent disease in the general population. It is estimated that 4% of men and 2% of women present SAHS with excessive daytime sleepiness, and there is a male/female ratio in the average ages of 2–3/1.1 Health consequences of this chronic sleep alteration and resulting intermittent hypoxemia include neuropsychiatric disorders, cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and the deterioration in quality of life of patients with SAHS.2–5 In order to quantify the variations in the quality of life of patients with SAHS, there are different health-related quality-of-life (HRQL) questionnaires that explore the limitation that this disease causes and how patients feel due to it. These questionnaires should be validated for their use and can be generic or specific. Among the generic questionnaires that have been validated in Spanish is the SF-36,6–8 one of the most widely used and evaluated quality-of-life tools, which, after a decade of use, has been shown to be useful for evaluating HRQL both in the general population as well as in patient groups. In contrast, specific questionnaires have been designed for a certain disease or symptom with the aim to optimize the properties of the tool and, especially, its sensitivity to change. They offer the advantage of being more sensitive for detecting the effects that certain therapeutic interventions have on patients.

Among the specific questionnaires designed for evaluating HRQL in patients with SAHS are the Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI)9 and the Québec Sleep Questionnaire (QSQ).10,11 The SAQLI evaluates four HRQL domains: (a) daily functioning; (b) social interactions; (c) emotional functioning; and (d) symptoms. An additional domain of treatment-related symptoms (e) may be added to measure the possible adverse effects of the treatment. The SAQLI, therefore, has the advantage of a section that assesses the response to treatment and its possible adverse effects, which makes it an adequate instrument for carrying out clinical trials and research papers.

Most HRQL questionnaires have been published in English. In order for them to be used in Spanish-speaking countries, a process of translation, transcultural adaptation and validation is required. To date, there are questionnaires validated in Spanish that measure the impact that sleep alterations may have on quality of life, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale,12 the Functional Outcomes Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ)13 or the specific questionnaire for patients with SAHS in the Spanish version of the QSQ.14 The latter has been successfully validated in Spanish by our group. Spanish, with 329 million speakers, is at this time the second most widely spoken language in the world after Chinese (1.213 billion) and before English (328 million).15 SAQLI, which has been validated in Chinese16 and Lithuanian,17 has been translated and successfully adapted to Spanish by our group.18 Although it is true that there is a previous paper validating a Spanish version of the SAQLI that was presented at the 2001 SEPAR congress,19 it had been done in a small number of patients who had not been treated, and therefore the possible negative impact that the SAHS treatment may have had was not analyzed. Given the fact that to date there are no publications in the literature of a version of the SAQLI validated in Spanish that analyses the response to treatment, the objective of our study was to analyze the reliability and the validity of the Spanish version of the HRQL Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index in order for it to be used in descriptive and/or evaluative studies in patients with SAHS in Spanish-speaking countries.

Material and MethodsStudy SampleThe one-year, multi-center study has a prospective design, for which 216 consecutive patients over the age of 18 were initially recruited from two centers from the province of Valencia with ample clinical and research experience in sleep pathologies, who had been sent to the SAHS outpatient consultation due to clinical suspicion. Excluded from the study were all those patients who presented significant unstable comorbidities that could influence the conclusions of the study, patients with important cognitive disorders and those who refused to take part in the study or were not able to fill out the questionnaires.

Data CollectionInformation was collected for all patients following a protocol for the following variables: age, sex, SAHS symptoms (chronic snoring, witnessed apneas, excessive daytime sleepiness, non-restful sleep, nocturnal episodes of asphyxia, frequent awakenings, nocturia, morning headaches, obesity or arterial hypertension), including the Spanish version of the Epworth test,12 the sleep study variables and those from the quality-of-life questionnaires used (FOSQ [Functional Outcomes in Sleep Questionnaire],13 SF-36 [Medical Outcome Survey-Short Form 36] and the Spanish version of SAQLI [see Annex 1]). The SAQLI, which was designed to be administered by a trained interviewer using Likert-type scales with seven response options, is made up of four HRQL domains: A) daily functioning (11 items); B) social interactions (13 items); C) emotional functioning (11 items); and D) symptoms (5 items). It has an additional fifth domain, E (5 items), of treatment-related symptoms. The overall score is obtained by adding the means obtained in the domains (A, B, C and D) divided by 4. If domain E is used, its recoded score is subtracted from domains A, B, C and D and the result is divided by 4. Before the study, all patients signed an informed consent form and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the participating centers.

Sleep StudyThe SAHS diagnosis was done by hospital respiratory polygraphy (RP) (Somnea® or Embletta®) or instead by conventional polysomnography (PSG) (Sleeplab, Jaeger®), with a manual analysis of all tracings. Treatment with nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) was considered in those patients who presented an apnea/hypopnea index (AHI) ≥5 together with symptoms related with SAHS and in those patients with AHI ≥30. Pressure adjustments were done by complete PSG or by a validated hospital auto-CPAP system (ResMed S8 AutoSet™ II Auto CPAP). CPAP compliance was considered to be good if used ≥4h per day. National guidelines were followed.1

Study ProtocolOn the initial visit, baseline data were collected in all patients following the protocol, including the general and SAHS symptom variables, those referring to the sleep study and the different quality of life tests (FOSQ, SF-36 and the Spanish version of the SAQLI), which were self-administered or assisted by an interviewer. On a visit one week later, 15 patients who were randomly chosen by a computer program once again answered the SAQLI in order to test its repeatability. Lastly, on a final visit at least 10 weeks after the prior visit, 23 patients were randomly selected from the group treated with CPAP who had criteria for good tolerance and compliance, with the aim to study the sensitivity to change of the questionnaire.

Statistical AnalysisThe SAQLI, FOSQ and the SF-36 were scored in accordance with the instructions of the authors of the original scales. All the statistical analyses were carried out with the SPSS program for Windows version 11.5 (Chicago, Illinois, USA). A descriptive analysis was done of the clinical parameters as well as the quality-of-life parameters expressed as mean±standard deviation in cases of quantitative variables, and as absolute value and percentage of the total for qualitative variables. For the comparison of two means, the Student's t test was used, and for the comparison of more than two means a variance analysis (ANOVA) was used with the Bonferroni correction or its corresponding non-parametric tests if the variables did not have a normal distribution (normality was confirmed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). For comparisons of two dichotomic variables, the χ2 test was used.

To analyze the internal consistency, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was calculated for each of the four domains of the questionnaire.20 According to Nunnany, an alpha value higher than 0.7 is considered sufficient to be able to use the questionnaire to make comparisons between patient groups.21 The construct validity was analyzed with a factorial analysis of principal components, whose applicability was confirmed with Bartlett's test of sphericity and the KMO measure (acceptable with values above 0.5). Each item was included in a certain factor if there was a minimum degree of saturation of 0.3 and an eigenvalue higher than 1. The number of factors was determined with no restrictions for structure according to the result of the scree test and the analysis of the sedimentation chart. In order to analyze the concurrent validity, Pearson's or Spearman's correlation coefficients were used depending on the normality of distribution of the variables, the different domains of the SAQLI questionnaire with the Epworth Test and the domains of the SF-36 and FOSQ questionnaires that referred to similar characteristics. The predictive validity was analyzed by comparing the groups of patients with severe and non-severe SAHS according to an AHI cut-point of 30 using the Student's t-test for independent means. The test–retest reliability (repeatability) was evaluated with the intraclass correlation coefficient. A good correlation was considered when ICC values were higher than 0.71, and moderate for values between 0.51 and 0.70.22 Lastly, sensitivity to change was analyzed after at least 10 weeks of effective CPAP treatment, comparing the values of all the domains of the SAQLI before and after treatment using the Student's t-test for repeat means. In any case, a P<.05 was considered significant.

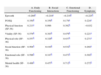

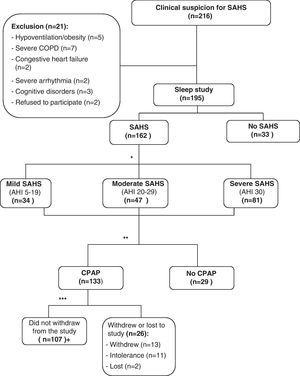

ResultsDuring the study period, 216 consecutive patients were sent to the outpatient sleep consultation due to clinical suspicion for SAHS. Twenty-one patients were excluded: 16 presented significant unstable comorbidities (5 hypoventilation-obesity, 7 severe COPD, 2 congestive heart failure, 2 severe arrhythmia); 3 patients were excluded due to important cognitive disorders; and, 2 refused to take part in the study. Out of the 195 patients that were finally included, 162 (83%) were diagnosed with SAHS, and their data were used to analyze the internal consistency and validity of the SAQLI questionnaire. The mean age of these patients was 58±12, with an Epworth scale of 10±4. Mean AHI was 37±15h−1 (range: 5–89), and body mass index (BMI) was 33±5.9kgm−2. The mean overall score of the FOSQ was 86±18, and for the different domains of the SF-36, the scores were: physical functioning, 77±24; physical role functioning, 85±27; bodily pain, 68±33; general health perceptions, 60±19; vitality, 57±21; social role functioning, 86±25; emotional role functioning 88±25, and mental health, 69±19. Out of the patients studied, 133 received CPAP treatment following the SEPAR guidelines. One hundred and seven patients tolerated and complied with a minimum of 4h per day of treatment. Out of the 26 remaining patients treated with CPAP, 13 abandoned the study, 11 did not tolerate the treatment and 2 were lost to the study during the follow-up period (Fig. 1). We found no statistically significant differences in the variables evaluated between the patients that abandoned the study compared with those who did not. Table 1 shows the results referring to the general description of the SAQLI questionnaire (mean, standard deviation, ranges, percentage of patients with ceiling and floor effects).

Methodological diagram of the study. *Following SEPAR guidelines. **Validation of the questionnaire. Fifteen patients were randomly chosen for the test–retest reliability. ***A use of ≥4h daily was considered good tolerance. aTwenty-three patients were randomly chosen for the sensitivity-to-change analysis.

General Description and Internal Consistency of the SAQLI Results.

| Domain | No. of items | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | % Floor Effect | % Ceiling Effect | Cronbach's Alpha |

| A. Daily function | 11 | 5.2 (1.2) | 5.4 | 2.4–7.0 | 0 | 2.5 | 0.82 |

| B. Social interaction | 13 | 5.4 (1.0) | 5.5 | 2.4–7.0 | 0 | 1.9 | 0.78 |

| C. Emotional function | 11 | 4.9 (1.1) | 5.0 | 1.8–7.0 | 0 | 1.2 | 0.82 |

| D. Symptoms | 5 | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.8 | 1.7–7.0 | 3.1 | 0 | 0.79 |

% Ceiling Effect, percentage of patients who reached the maximal score in each scale or in the total score of the questionnaire; % Floor Effect, number of patients who reached the minimal score in each scale or in the total score of the questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

The Spearman's correlation coefficient among the different items of the questionnaire varied in each of the domains. For the daily functioning domain, the correlations were the following: in the most important daily activities subdomain, the range was between 0.305 and 0.564; in secondary activities, between 0.116 and 0.538, and in the general functioning subdomain, between 0.177 and 0.460, which were all significant. In the social interaction domains, the correlations were between 0.034 and 0.568, the majority of which were significant. Last of all, in the emotional functioning domain, the correlations fluctuated between 0.100 and 0.528. In each of the domains, most of the correlations were significant. The Cronbach's alpha that was obtained for each of the domains was higher than 0.7 (Table 1).

Construct ValidityBartlett's test of sphericity was significant (P<.0001) and the KMO measure was 0.691. All of this allowed for a factor analysis to be applied to the correlation matrix. By means of the scree test and the analysis of the sedimentation rate chart, four factors were determined that explained 42.5% of the variance. The rotation used, given the correlation between these factors, was orthogonal (varimax) (Table 2). All the items were input into the analysis. The first factor included 18 items, with an explained variance of 21.4%. Its structure was similar to the daily functioning scale of the original questionnaire and grouped 9 of the 11 items of this scale. It also included four items of the domain that referred to social interactions, and five referring to the emotional function domain. The second factor explained 8.8% of the variance and was composed of four items, all of them belonging to the domain of social interaction. The third factor, made up of 11 items, most of which belonged to the emotional functioning domain, explained another 7% of the variance. Lastly, the fourth factor was made up of seven items, five of which corresponded with the symptoms domain of the original questionnaire.

Matrix of the Four Factors Extracted by the Factorial Analysis of Main Components with Varimax Rotation.

| Item | Factor A | Factor B | Factor C | Factor D |

| A. Daily functioning | ||||

| A1 | 0.510 | 0.454 | ||

| A2 | 0.637 | |||

| A3 | 0.384 | 0.425 | ||

| A4 | 0.343 | |||

| A5 | 0.701 | |||

| A6 | 0.120 | |||

| A7 | 0.688 | |||

| A8 | 0.706 | |||

| A9 | 0.370 | |||

| A10 | 0.475 | |||

| A11 | 0.715 | |||

| B. Social interaction | ||||

| B1 | 0.759 | |||

| B2 | 0.070 | |||

| B3 | 0.592 | |||

| B4 | 0.382 | 0.457 | ||

| B5 | 0.383 | 0.432 | ||

| B6 | 0.378 | |||

| B7 | 0.466 | |||

| B8 | 0.540 | |||

| B9 | 0.479 | 0.468 | ||

| B10 | 0.418 | |||

| B11 | 0.506 | |||

| B12 | 0.583 | |||

| B13 | 0.624 | |||

| C. Emotional functioning | ||||

| C1 | 0.632 | |||

| C2 | 0.534 | |||

| C3 | 0.490 | |||

| C4 | 0.632 | |||

| C5 | 0.588 | |||

| C6 | 0.656 | |||

| C7 | 0.617 | |||

| C8 | 0.694 | |||

| C9 | 0.756 | |||

| C10 | 0.397 | |||

| C11 | 0.317 | |||

| D. Symptoms | ||||

| D1 | 0.469 | |||

| D2 | 0.634 | |||

| D3 | 0.550 | |||

| D4 | 0.685 | |||

| D5 | 0.815 | |||

The values less than 0.3 are omitted, except in the values of the items B2 and A6.

Table 3 shows the existing correlation (Spearman's coefficient) between the Epworth test and the domain scores from the FOSQ and SF-36 questionnaire compared with the domain scores from the SAQLI questionnaire that measured similar characteristics. Moderate and low correlations were observed, and almost all were significant.

Spearman's Correlation Between the Scores of the Domains of the Spanish Version of the Sleep Apnea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI) Questionnaire and the Related Tools of Measurement.

| A. Daily Functioning | B. Social Interactions | C. Emotional Functioning | D. Symptoms | |

| Epworth | −0.269b | −0.210a | −0.219b | −0.225b |

| FOSQ | 0.350b | 0.359b | 0.179a | 0.224a |

| Physical function (SF-36) | 0.213a | 0.096 | 0.392b | −0.032 |

| Vitality (SF-36) | 0.579b | 0.383b | 0.479b | 0.221a |

| Physical role (SF-36) | 0.557b | 0.329b | 0.437b | 0.271a |

| Social function (SF-36) | 0.564b | 0.410b | 0.532b | 0.292a |

| Emotional role (SF-36) | 0.596b | 0.347b | 0.473b | 0.302b |

| Mental health (SF-36) | 0.488b | 0.457b | 0.712b | 0.272b |

The group of patients with mild-moderate SAHS was compared with those who presented severe SAHS. The results that were obtained were similar to those reported by the authors of the validation of the original questionnaire, who observed that the correlations between the physiological measurements in basal state and the results in the quality-of-life measurement reflected in the different domains of the questionnaire were not significant (P>.05).

RepeatabilityThe following infraclass correlation coefficients were obtained for each of the four domains: daily functioning, 0.940 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.78–0.96); social interaction, 0.977 (95% CI, 0.91–0.99); emotional functioning, 0.953 (95% CI, 0.82–0.98); and symptoms, 0.540 (95% CI, 0.09–0.86).

Sensitivity to ChangeIn Table 4, the scores are shown for the domains obtained before and after treatment. After 10 weeks of effective treatment with CPAP, a statistically significant change was observed in each of the domains of the questionnaire, as well as in the total score (P<.01).

Analysis of the Sensitivity to Change; Pre-Treatment and Post-Treatment With CPAP Scores for the Different Domains of the SAQLI Questionnaire.

| SAQLI Domains | Pre-treatment | Post-treatment | P |

| A. Daily functioning | 5.1 (1.9) | 6.1 (1.1) | <.01 |

| B. Social interaction | 4.9 (1.1) | 6.1 (1.1) | <.01 |

| C. Emotional functioning | 4.8 (1.1) | 5.8 (0.9) | <.01 |

| D. Symptoms | 2.6 (1.1) | 4.6 (1.9) | <.01 |

| E. Symptoms related with treatment (recodified) | – | 1.7 (0.3) | – |

| Overall SAQLI score | 4.4 (1.1) | 5.6 (0.9) | <.01 |

Pre-treatment and post-treatment scores obtained in each of the domains, as well as the overall score of the SAQLI, are shown as means and standard deviation.

According to our results, the Spanish version of the SAQLI questionnaire presents an internal consistency, validity and repeatability that are adequate for use in SAHS patients. Likewise, this questionnaire has been demonstrated to be sensitive to the change produced by CPAP treatment.

The internal consistency of the tool was high, and the coefficients obtained in each domain surpassed 0.7, which is generally considered acceptable. In the construct validity analysis, we observed a structure similar to that of the original questionnaire. The factor analysis showed, after analyzing the sedimentation chart, that the choice of four factors was similar to the distribution of the SAQLI. These factors explained 42.5% of the variance. In the first factor, referring to daily functioning, 9 out of the 11 items of this domain were included. The second factor only had items pertaining to the social interaction domain. The third and the fourth factors were mostly made up of items corresponding with emotional functioning and symptoms, respectively. Therefore, there is a good correlation between the extracted factors with the domains of the original questionnaire.

When we studied the concurrent validity of the test, we observed that there was a moderate correlation between the daily functioning domain and the score in the vitality, social function and physical role domains of the SF-36. This agrees with the results obtained in the independent validation of the SAQLI, which already demonstrated a moderate correlation with the physical role domain and a strong correlation with the vitality domain of the SF-36.23 The emotional functioning domain presented a strong correlation with the mental health domain of the SF-36 questionnaire and a moderate correlation with the social functioning domain of this same survey. The social interaction domain presented a weak correlation (although somewhat stronger than with the other domains) with social functioning and mental health of the SF-36. The authors of the original validation found a moderate correlation between the Epworth test and the symptoms domain of the SAQLI, although in the validation of the Spanish version both scales presented a weak correlation. Despite the fact that the correlations found between the SAQLI and the related tools of measurement were moderate or weak, it should be emphasized that most of these were statistically significant.

As for the predictive validity of the test, it was not demonstrated that the HRQL was worse in patients with severe SAHS than in those who presented a mild or moderate degree of the disease. This fact has special clinical relevance as it limits its utility in standard clinical practice. In the validation of the QSQ questionnaire done by the authors of the present study, there was an observed worsened HRQL in patients who presented severe SAHS versus mild or moderate SAHS. Therefore, we consider this to be a disadvantage of the SAQLI compared with the QSQ questionnaire, which has been shown to be more appropriate for distinguishing between SAHS severities.

The test–retest reliability demonstrated good agreement in the daily functioning, social interaction and emotional functioning domains, and moderate agreement in the symptoms domain.

In the analysis of the sensitivity to change after CPAP treatment, statistically significant differences were observed in all the domains included in the questionnaire. Nonetheless, the magnitude of change was discretely less than in the original publication,9 obtaining results that were very similar to those reached in the independent validation of the questionnaire done by Lacasse.23 We believe that the explanation of this phenomenon in the original study is due to the fact that the sensitivity to change was studied in a small patient sample effectively treated with CPAP, while both in the independent validation of the original questionnaire as well as in our study, the number of patients was considerably greater. Due to all this, our results support the use of the Spanish version of the SAQLI questionnaire after the application of CPAP treatment.

As for the study limitations, it should be mentioned that a comparative analysis was not done between the capacity for change in those who complied or did not comply with treatment, as well as the size effect, as it is a relatively small sample of individuals. Furthermore, the disappearance of apneas was not confirmed with another sleep test at the end of the study. Nevertheless, we think that these limitations do not compromise the results obtained in the validation.

In conclusion, our validation study indicates that the Spanish version of the SAQLI represents a valid measurement of HRQL and has adequate psychometric characteristics to be used in patients with SAHS when compared with the original questionnaire. Furthermore, it has demonstrated sensitivity to change induced by CPAP treatment.

FundingThis article has received the following grants: Valencian Foundation of Pulmonology Grant (2010) and Gasmedi 2000 Grant (2008).

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Catalán P, et al. Consistencia interna y validez de la versión española del cuestionario de calidad de vida específico para el síndrome de apnea del sueño: Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:431–42.

The copyright of the English version of the Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index belongs to Dr. W. Ward Flemons, Alberta Lung Association Sleep Disorders Centre, Foothills Hospital, 1403 29th Street N.W., Calgary, AB, T2 N 2T9 Canada.