The evaluation of pleural effusion (PE) includes various techniques, including pleural biopsy (PB). Our aim was to study the diagnostic yield of Tru-Cut needle PB (TCPB) and to define clinical/radiological situations in which TCPB might be indicated as an initial procedure.

MethodologyRetrospective study of TCPB in a hospital center (2010–2012). Cases of pleural lesions without effusion were excluded. Clinical and radiological variables, diagnostic yield, TCPB complications and factors associated with the diagnostic yield of the combination of TCPB and thoracocentesis as initial procedure were analyzed.

ResultsOne hundred and twenty-seven (127) TCPB were reviewed: 29.1% were cases of malignant PE and in 18.9% the cause of the PE could not be determined. The diagnostic yield of TCPB for tuberculosis was 76.5% (13/17) and 54% (20/37) for malignant PE. Complications occurred in 4.7% of the cases. In 72 patients with a final definitive diagnosis, TCPB was performed at the same time as the initial thoracocentesis. Diagnostic yield for the combination of TCPB/cytology as an initial technique was 43% (31/72) compared to 12.5% (9/72) for cytology only (P=.01). The only predictive variable for the indication of TCBP as an initial technique was a PE volume >2/3 (P=.04).

ConclusionsTCPB is safe and provides an acceptable diagnostic yield, particularly when combined with simultaneous cytology in the evaluation of PE of various aetiologies. Radiological criteria may help guide the selection of patients who could benefit from this technique as an initial procedure combined with thoracocentesis.

El estudio del derrame pleural (DP) incluye distintas técnicas, como la biopsia pleural (BP). Los objetivos han sido analizar la rentabilidad diagnóstica de la BP con aguja Tru-cut (BPTC) y determinar si existen factores clínico-radiológicos que permitan indicar la realización de la BPTC como primer procedimiento.

MetodologíaEstudio retrospectivo de las BPTC de un centro hospitalario (2010-2012). Se excluyeron casos de lesiones pleurales sin DP. Se analizaron variables clínico-radiológicas, la rentabilidad diagnóstica, las complicaciones de la BPTC y los factores asociados con la rentabilidad diagnóstica de la combinación de la BPTC y toracocentesis como primer procedimiento.

ResultadosSe revisaron 127 BPTC; el 29,1% fueron DP malignos y en el 18,9% no se llegó a la causa del DP. La rentabilidad diagnóstica de la BPTC para tuberculosis fue del 76,5% (13/17) y para DP malignos, del 54% (20/37). Hubo un 4,7% de complicaciones. En 72 pacientes con diagnóstico final conocido, la BPTC se hizo simultáneamente a la primera toracocentesis. La rentabilidad diagnóstica de la combinación de BPTC/citología como primera técnica fue del 43% (31/72) frente al 12,5% (9/72) de la citología sola (p=0,01). La única variable predictora para la indicación de BPTC como técnica inicial fue la cuantía del DP>2/3 (p=0,04).

ConclusionesLa BPTC es segura y ha demostrado una rentabilidad diagnóstica aceptable, sobre todo cuando se combina con la citología simultánea en el estudio del DP de diferentes etiologías. La aplicación de criterios radiológicos podría ayudar a seleccionar en qué pacientes podría estar indicada como primera técnica inicial junto a la toracocentesis.

The evaluation of a patient with pleural effusion (PE) involves a series of clinical and radiological procedures and analysis of the pleural fluid (PF).1,2 It is generally difficult to determine the etiology of PE with thoracocentesis alone, particularly when there is a suspicion of malignant disease, since cytology alone is diagnostic in less than 60% of cases.1,2 Pleural biopsy (PB) for histological evaluation is the next procedure in the diagnostic algorithm of PE.1–3 Obtaining samples of pleural tissue can be achieved by blind PB, computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound-guided closed PB or thoracoscopy.1–5 Closed PB is considered the first step in a patient with suspected tuberculosis in a geographical region with a high prevalence of the disease, and thoracoscopy is the gold standard technique, being the technique of choice in the case of exudative effusion with negative cytology and suspected malignant disease.1,2 Patients with transudates and exudates and those with malignant PE (MPE) present different clinical and radiological features when compared with patients with benign PE or tuberculosis PE (TBPE). Therefore, in special circumstances, depending on the pre-test clinical suspicion, closed PB could be an initial test in patients with PE.6

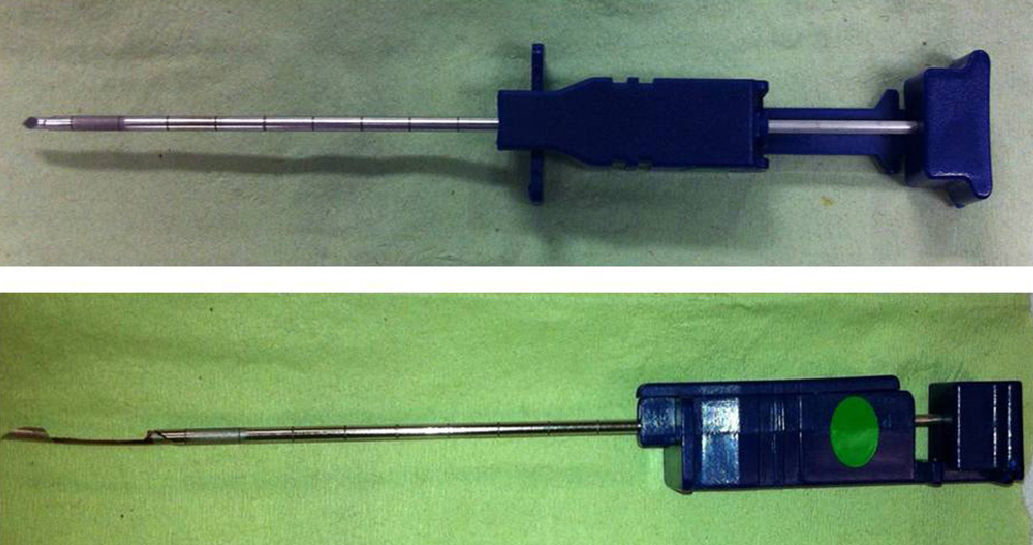

Various needles are available for closed PB. In 1989, McLeod et al.7 first described the Tru-cut needle, a thin instrument with a sharp-edged sample notch at the distal end, for performing pleural biopsies. One of the features of the Tru-cut needle, compared to other types of needle, is its small caliber, which may reduce the risk of complications. Tru-cut needle PB (TCPB) is particularly indicated in PE with pleural thickening shown on CT and suspected malignant disease.1,8 Surprisingly, few studies have been done in non-selected patients with PE alone, and those have been based on a small number of cases.7,9,10

Thoracocentesis is the first procedure in the diagnostic algorithm of PE.1,2 Closed PB together with the first thoracocentesis as an initial technique could improve PB diagnostic yield before other more invasive techniques, such as thoracoscopy, are performed. The first objective of this study was to analyze the diagnostic yield of TCPB in MPE and TBPE in a consecutive non-selected series of patients with PE. A further objective was to analyze the diagnostic yield of PB plus cytology in the evaluation of PE of different etiologies, and to determine factors that might indicate the simultaneous performance of both techniques as an initial procedure in the diagnostic algorithm of PE.

MethodologyAn observational, retrospective study that included all TCPBs performed between 2010 and 2012 in the Bronchopleural Techniques Unit of the Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe in Valencia, Spain. Data were retrieved from the registry of the Anatomical Pathology department and the Bronchopleural Techniques Unit. Inclusion criterion was patients with PE, irrespective of the presence of pleural thickening shown on CT. Patients with masses or lesions in the pleural cavity without the presence of free fluid were excluded.

The diagnostic criteria used for classifying the etiology of the PE were those recommended by the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Chest Surgery2:

- -

MPE: cytohistological diagnosis of malignant disease in the pleural space.

- -

TBPE: Positive Löwenstein culture of PF or PB and/or biopsy showing granulomas, in the absence of other pleural granulomatous diseases, or resolution of PE after completion of empirical anti-tuberculosis treatment.

- -

Parapneumonic PE (PPPE): presence of cough, fever, and X-ray showing pulmonary infiltrates that resolve after antibiotic treatment. Patients with frank pus were excluded from this group.

- -

Miscellaneous: specific diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of other PE.

- -

Non-malignant PE of unknown origin: PE of unknown origin in patients with any of the following criteria: (a) non-specific pleuritis examined by thoracoscopy, thoracotomy or autopsy, and (b) absence of symptoms or recurrent PE in clinical or radiological follow-up over one year.11

The epidemiological characteristics of the patients included in the study were recorded. Symptoms analyzed included constitutional syndrome, presence of fever, chest pain or dyspnea. Symptoms were considered chronic if they had persisted for longer than one month, acute for less than 7 days, and subacute for a period between the two.

Radiological evaluation of PE included the volume observed on chest X-ray and was classified according to the following criteria: PE was massive or large when there was opacification of the whole hemithorax or up to the aortic arch (greater than two thirds), PE was small if there was opacification in the lung base with the typical meniscus sign (less than one third), and medium if opacification was between two thirds and one third of the hemithorax.

The presence or absence of pleural thickening shown on the chest CT was also recorded. Pulmonary or pleural masses, pulmonary atelectasis, lymphadenopathies or other masses in solid organs were considered suggestive of malignant disease.

Pleural ProceduresThe PB procedure was similar in all cases. Ultrasound with a convex 3.5MHz transducer was used to select the point of entry and PBs were performed by two expert pulmonologists or supervised trainee physicians with an accumulated experience of over 200 closed PBs. The patient was placed in a sitting position with the arm on the same side as the PE rose above the contralateral shoulder. The technique was performed under sterile conditions and local anesthesia with 2% mepivacaine was applied. A Tru-cut needle (see Fig. 1) was used in all cases. Patients were not randomized in any way and a TCPB or thoracoscopy was performed on the indication of the treating physician. With regard to the results of the closed PB, the retrieval of representative specimens of pleural tissue and the diagnostic yield of patients with MPE (histological diagnosis of malignancy in the pleural space) and TBPE (positive Löwenstein culture of PF or PB and/or granulomas in the PB, in the absence of other pleural granulomatous diseases) were analyzed. Any PB complications were recorded.

Statistical AnalysisResults were expressed as percentages and absolute frequencies for qualitative variables and as mean and standard deviation for numerical variables. Discrete variables were compared using the Chi-squared test or the Fischer's exact test. To determine factors that could independently indicate the performance of simultaneous PB and thoracocentesis as an initial procedure to improve the diagnostic yield of the PB, a bivariate analysis was performed using the Chi-squared test. No multivariate analysis was performed because only one factor among those evaluated was associated with a statistically significant result. Statistical significance was set at P<.05. Analyses were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, US).

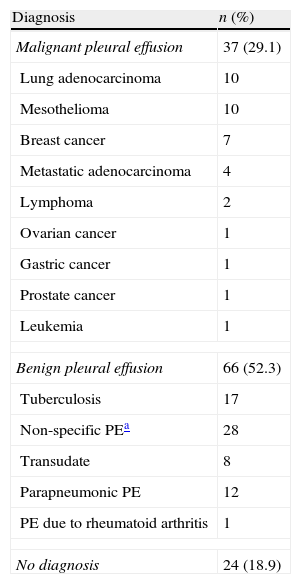

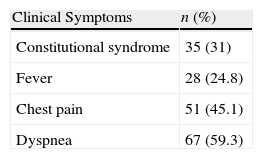

ResultsDuring the study period, 127 TCPBs were performed in 127 patients. A total of 65.4% (83/127) were men and the mean age was 62.6±14 years. Thirty-seven (29.1%) patients had MPE and 66 (52.3%) had benign PE. In 24 (18.9%) patients, no diagnosis was obtained with the thoracocentesis and PB techniques and no thoracoscopy or one-year clinical and radiological follow-up were performed, so these cases were considered undiagnosed. Table 1 shows the final diagnosis of all patients included in the study, and Table 2 describes the clinical characteristics (these data were unavailable in 14 patients).

Final Diagnosis of Pleural Effusion (n=127).

| Diagnosis | n (%) |

| Malignant pleural effusion | 37 (29.1) |

| Lung adenocarcinoma | 10 |

| Mesothelioma | 10 |

| Breast cancer | 7 |

| Metastatic adenocarcinoma | 4 |

| Lymphoma | 2 |

| Ovarian cancer | 1 |

| Gastric cancer | 1 |

| Prostate cancer | 1 |

| Leukemia | 1 |

| Benign pleural effusion | 66 (52.3) |

| Tuberculosis | 17 |

| Non-specific PEa | 28 |

| Transudate | 8 |

| Parapneumonic PE | 12 |

| PE due to rheumatoid arthritis | 1 |

| No diagnosis | 24 (18.9) |

PE: pleural effusion.

Suitable pleural tissue specimens were obtained in 78% (109/127) of the cases.

The diagnostic yield of the TCPB for TBPE was 76.5% (13/17), and for MPE 54% (20/37). In the MPE patient group (n=37), pleural thickening was observed in 12 cases. In this patient subgroup, diagnostic yield of PB increased to 66.6%.

In the TBPE patient group (n=17), only 1 had pleural thickening. In that patient, TCPB was diagnostic (diagnostic yield 100%).

Complications were encountered in 4.7% of cases: 1 patient had vasovagal syncope, 2 had pneumothorax and 2 hemothorax; an endothoracic drainage tube was required in 3 of these cases.

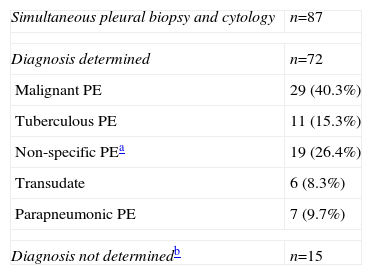

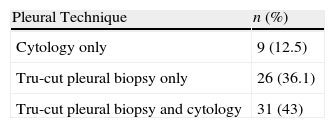

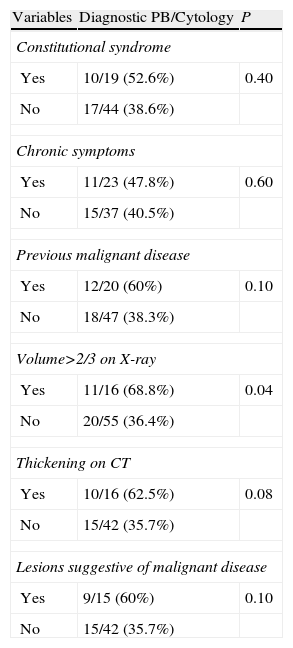

In 68.5% (87/127) of the patients, the first thoracocentesis was performed with simultaneous PB. The final cause of PE in this patient subgroup was determined in 72 cases (see Table 3). The diagnostic yield in this subgroup with combined closed PB and cytology as an initial technique was 43% (31/72) compared to 12.5% (9/72) for cytology alone for all PEs of different etiologies (P=.01), and 75.8% (22/29) for MPE and 81.8% (9/11) for TBPE. Table 4 shows the diagnostic yield of the different pleural procedures in the patient subgroup that underwent PB and cytology as an initial procedure. Table 5 shows the differences in yield for combination of TCPB and cytology as an initial procedure according to various clinical and radiological factors. No multivariate analysis was performed as only 1 of the factors evaluated was associated with a statistically significant result. The only predictive variable for the indication of TCPB with cytology as an initial technique in the evaluation of PE was a radiological finding of PE occupying over two thirds of the hemithorax (P=.04). There was a clear trend toward pleural thickening shown on chest CT as a predictor but statistical significance was not reached (P=.08).

Final Diagnosis of Pleural Effusion in the Patient Subgroup Undergoing Pleural Biopsy and Cytology as Initial Procedure.

| Simultaneous pleural biopsy and cytology | n=87 |

| Diagnosis determined | n=72 |

| Malignant PE | 29 (40.3%) |

| Tuberculous PE | 11 (15.3%) |

| Non-specific PEa | 19 (26.4%) |

| Transudate | 6 (8.3%) |

| Parapneumonic PE | 7 (9.7%) |

| Diagnosis not determinedb | n=15 |

PE: pleural effusion.

Differences in Yield of Pleural Biopsy Plus Cytology as Initial Procedure in the Examination of Pleural Effusion According to Different Clinical and Radiological Factors (n=72).

| Variables | Diagnostic PB/Cytology | P |

| Constitutional syndrome | ||

| Yes | 10/19 (52.6%) | 0.40 |

| No | 17/44 (38.6%) | |

| Chronic symptoms | ||

| Yes | 11/23 (47.8%) | 0.60 |

| No | 15/37 (40.5%) | |

| Previous malignant disease | ||

| Yes | 12/20 (60%) | 0.10 |

| No | 18/47 (38.3%) | |

| Volume>2/3 on X-ray | ||

| Yes | 11/16 (68.8%) | 0.04 |

| No | 20/55 (36.4%) | |

| Thickening on CT | ||

| Yes | 10/16 (62.5%) | 0.08 |

| No | 15/42 (35.7%) | |

| Lesions suggestive of malignant disease | ||

| Yes | 9/15 (60%) | 0.10 |

| No | 15/42 (35.7%) | |

PE: pleural effusion; CT: computed tomography.

The role of closed PB in the diagnosis of suspected MPE has been questioned because diagnostic yield may be lower than with cytology, and thoracoscopy has been shown to be more useful.1,8,12 However, yield may increase from 40% for cytology alone up to 74% when cytology is combined with PB.12 In this study, performing a TCPB along with the first thoracocentesis significantly improved diagnostic yield compared to cytology alone in evaluation of PE of different etiologies. Unlike the results previously described for cytology,1–3 the diagnostic yield in this analysis was very low. The yield from cytology depends on factors such as specimen preparation, the experience of the cytologist and the type of tumor, which may explain the variability in these results.1

Patients with MPE may present clinical and radiological differences compared to those with benign PE. In a study published by Ferrer et al.,13 a multivariate analysis was performed to determine which variables could predict MPE. The combination of absence of fever, persistence of symptoms for longer than one month, bloody PF and CT findings suggestive of malignant disease led to the correct classification of PEs as malignant in 95% of cases.13

In our study, symptoms, duration of symptoms or history of malignant disease did not predict favorable results for PB as an initial procedure. In the opinion of the authors, these results probably reflect lack of specificity in the case history of patients with PE, and that the majority of data considered suggestive of malignant disease in clinical practice have not been shown to have a high predictive value.1,2,8 Moreover, the factor “history of malignant disease” did not take into account the tumor type, degree of differentiation or initial staging.

One of the most important aspects of this study may be the applicability of the results. Radiological tests and PF analysis are the initial procedures undertaken in the evaluation of patients with PE, and PB is the second step for undiagnosed cases. According to our results, larger pleural effusions with more fluid are associated with a malignant etiology. In these cases, performing a PB along with the thoracocentesis seems to be the most appropriate approach, especially if the yield for cytology is low. In centers where the cytology yield is very low, PB plus cytology may be indicated as an initial technique in patients with PE occupying two thirds of the hemithorax on chest X-ray.

Pleural thickening shown on CT increased the diagnostic yield of TCPB in patients with MPE and TBPE; however, although a certain trend was observed, in the bivariate analysis this finding was not associated with statistically significant differences or with the existence of lesions suggestive of malignancy on CT. The retrospective study design may be a limitation, and it is possible that this finding was underdiagnosed. As this was a non-randomized study, PB was not performed systematically as the initial procedure in all patients in whom CT was performed, and this may explain these results.

Different models of needle are available for performing closed PB. The Abrams needle is the most widely used and has demonstrated a high diagnostic yield, particularly in cases in which image-guided PB is performed and tuberculosis is suspected.14,15 However, few studies have analyzed the yield of TCPB in a consecutive series of non-selected patients.7,9,10

In a prospective study analyzing the yield of ultrasound-guided PB using the Abrams needle compared to a Tru-cut needle, the image-guided Abrams needle showed greater diagnostic sensitivity compared to the Tru-cut needle in the diagnosis of TBPE (81% versus 62%; P=.022).15 In this study, however, the diagnostic sensitivity of TCPB was better, reaching 76.5% for tuberculosis. One important aspect is that, unlike previous reports, in this study patients with suspected tuberculosis were not selected, and all cases of PB were included consecutively, irrespective of the presence of pleural thickening.15

TCPB is especially indicated in PE with pleural thickening shown on CT and suspected malignant disease.1,8 In patients with pleural thickening due to mesothelioma, a diagnostic yield of 86% has been reported.16 Maskell et al.17 described a diagnostic sensitivity of 87%, for CT-guided TCPB in patients with pleural thickening, irrespective of the cause of the PE. In this study, mesothelioma was one of the most common causes of MPE, and this entity typically presents as pleural thickening or masses associated with PE. However, as mentioned above, although the diagnostic yield of TCPB increased with pleural thickening, statistical significance was not reached.

This is the first study to analyze the yield of closed TCPB in a large series of non-selected patients with PE. In the first study published, McLeod et al.,7 in a small series of 36 patients, described a diagnostic yield for TBPE and MPE of 90.9% and 50%, respectively. The results reported here are similar for MPE; however, unlike our study, McLeod et al. excluded small PEs. The main advantage of the Tru-cut needle compared to other types of needle may be its small diameter, making it a simple, well-tolerated procedure with a low complication rate. This is one of the main reasons for proposing the combination of PB with thoracocentesis as an initial procedure.

Ultrasound-guided pleural procedures involve fewer risks.18 In this study, no major complications were reported, and pneumothorax occurred in patients with small PEs (results not shown).

Gopal et al.19 analyzed closed PB trends in a hospital in the United States between 1996 and 2006. The rate of blind PBs performed fell from 77% in 1996 to 26% in 2006 (P<.001). During the same period, the number of image-guided PB increased significantly from 7% to 53% (P<.001).19

Despite the importance that image-guided pleural techniques have acquired, it should be remembered that thoracoscopy offers greater diagnostic accuracy (over 95%), and has the advantage of being a simultaneous therapeutic intervention.3–5

This study has its limitations, some of which have been discussed above and are typical of a retrospective study. Furthermore, all the patients included were from a single center, so the results of the diagnostic yield of pleural techniques such as cytology cannot be generalized.

The authors conclude that TCPB is safe and provides an acceptable diagnostic yield, particularly when PB is combined with cytology as an initial simultaneous procedure in the evaluation of PE of different etiologies. The application of radiological criteria may aid in the selection of patients in whom the combination of PB and thoracocentesis may be indicated as an initial procedure. However, prospective, randomized studies are needed to confirm the usefulness of these criteria for indicating PB as an initial procedure before they can be incorporated into clinical practice.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank Dr Alberto Fernández Villar, Head of the Pulmonology Department of the Complexo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, for his assistance in reviewing this article.

Please cite this article as: Botana Rial M, Briones Gómez A, Ferrando Gabarda JR, Cifuentes Ruiz JF, Guarín Corredor MJ, Manchego Frach N, et al. Biopsia pleural con aguja Tru-cut y citología como primer procedimiento en el estudio del derrame pleural. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:313–317.