Correctly diagnosing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) continues to be a challenge at all levels of care,1,2 and the identification of cases is significantly impacted by factors such as the slow onset of symptoms or the failure of the health system to perform all the necessary spirometries. Consequently, in Spain, a significant rate of underdiagnosis has been described,3,4 and the search for alternative diagnostic methods has become a priority.5 One of the clinical settings that could be used to assist case detection is the smoking cessation clinic. A number of pilot projects have recently been developed to determine the ability of smoking cessation units to detect COPD.6,7 Although these studies suggest that these units offer ample opportunity, the small samples sizes mean that these results need to be confirmed in larger studies performed nationwide. The SEPAR Smoking and COPD Areas proposed Project 1000-200 with the aim of evaluating the capacity of smoking cessation units to detect COPD in Spain.

Between April and May 2019, we conducted a multicenter cross-sectional observational study that included consecutive patients evaluated for smoking cessation with no previous diagnosis of COPD. In line with the known prevalence of COPD in Spain at the time of the study,3 the objective was to evaluate 1000 cases to identify 200 patients with bronchial obstruction on spirometry. During the clinical interview, patient data were collected on age, sex, cumulative pack-year index, intention to make a serious attempt to quit smoking, and dyspnea according to the modified MRC scale. Patients subsequently performed a prebronchodilator spirometry to assess the presence of bronchial obstruction, which could be complemented with a bronchodilator test if researchers saw fit. All spirometries were quality-controlled and performed by trained, experienced personnel, according to current recommendations.8 These data were used to calculate the percentage of patients with bronchial obstruction on spirometry and those who met diagnostic criteria for COPD associated with a cumulative consumption of ≥10 pack-years and respiratory symptoms (mMRC≥1). Bronchial obstruction severity was categorized into grades 1–4 according to the 2021 Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) document.9

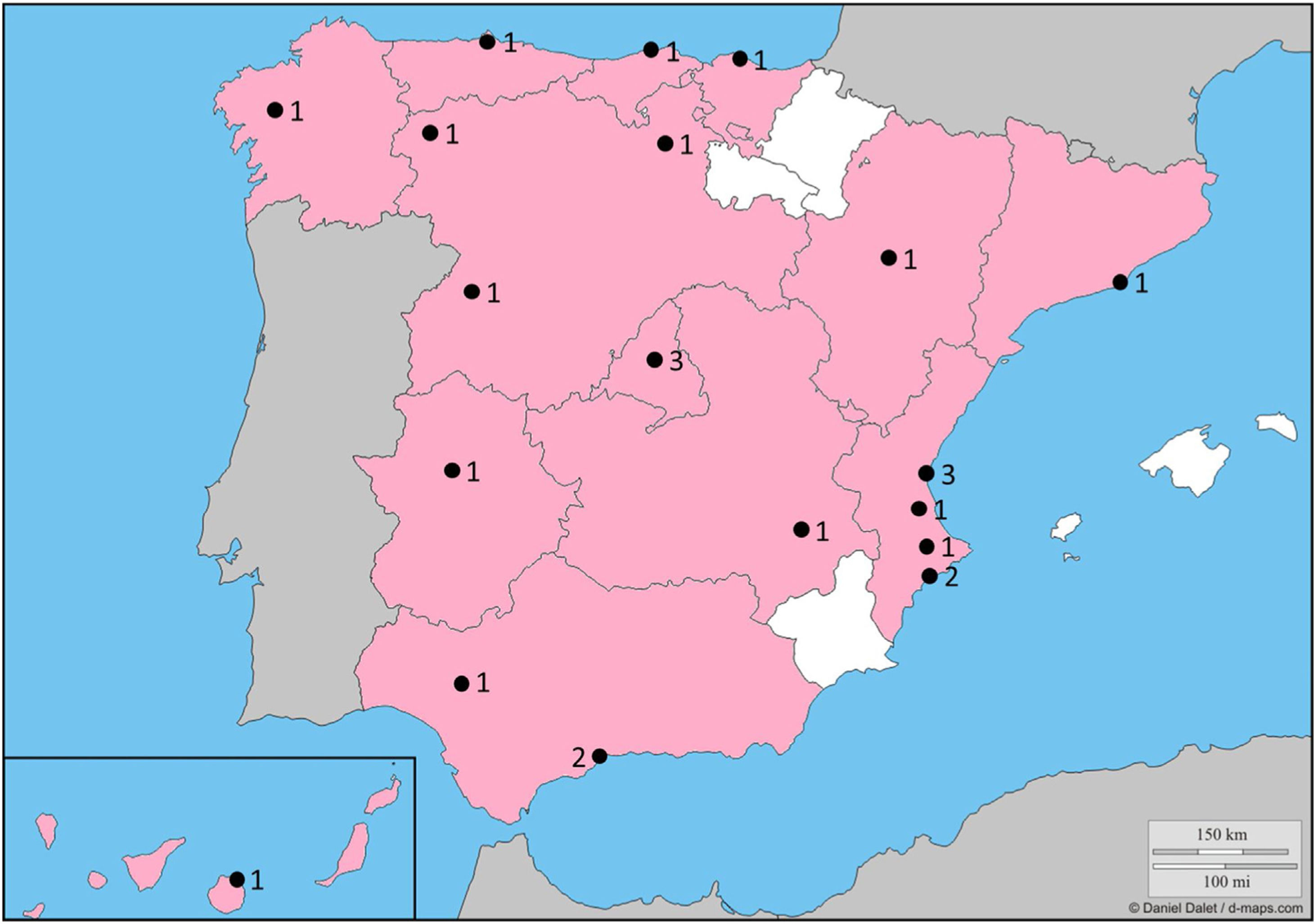

Overall, 25 sites participated in 13 of the 17 regions of Spain (Fig. 1). During the study period, 1020 active smokers were evaluated, with a mean age of 55.9 (standard deviation 10.0) years, 558 (54.7%) women, 30.8 (17.3) pack-years, of whom 699 (68.5%) stated that they intended to quit smoking in the next few days. Spirometries were performed as follows: 669 (65.6%) prebronchodilator only, 335 (32.8%) pre- and postbronchodilator, and 16 (1.6%) postbronchodilator only. Postbronchodilator spirometry (or prebronchodilator spirometry if postbronchodilator was not available) data showed that spirometry patterns were normal in 696 (68.2%) patients, restrictive (FVC<80% and FEV1/FVC>70%) in 78 (7.6%), obstructive (FVC≥80% and FEV1/FVC<70%) in 207 (20.3%), and mixed (FVC<80% and FEV1/FVC<70%) in 39 (3.8%). Almost a quarter (246, 24.1%) of patients showed bronchial obstruction on spirometry (FEV1/FVC<70% postbronchodilator or prebronchodilator, if postbronchodilator not available). Bronchial obstruction grades were: GOLD 1: 115 (11.3% of sample; 46.7% of patients with obstruction); GOLD 2: 110 (10.8% of sample; 44.7% of patients with obstruction); GOLD 3: 19 (1.9% of sample; 7.7% of patients with obstruction); and GOLD 4: 2 (0.2% of sample; 0.8% of patients with obstruction). Patient characteristics by presence or absence of bronchial obstruction are summarized in Table 1. In total, 168 (16.5%) patients had a diagnosis of COPD according to bronchial obstruction, the presence of symptoms, and sufficient cumulative tobacco use.

Description of Study Patients by Presence of Bronchial Obstruction.

| Variable | No Obstruction (n=774) | Obstruction (n=246) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women (n) | 462 (59.7) | 96 (39.0) | <.001 |

| Age (years) | 54.2 (9.6) | 61.1 (9.3) | <.001 |

| Accumulated exposure (pack-years) | 28.6 (15.8) | 37.7 (19.9) | <.001 |

| Dyspnea (mMRC) | <.001 | ||

| Grade 0 | 423 (54.7) | 77 (31.3) | |

| Grade 1 | 296 (38.2) | 110 (44.7) | |

| Grade 2 | 49 (6.3) | 53 (21.5) | |

| Grade 3 | 3 (0.4) | 4 (1.6) | |

| Grade 4 | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Spirometry type | <.001 | ||

| Prebronchodilator only | 653 (84.4) | 16 (6.5) | |

| Pre- and postbronchodilator | 120 (15.5) | 215 (87.4) | |

| Postbronchodilator only | 1 (0.1) | 15 (6.1) | |

| FVC (%) | 101.8 (18.6) | 101.1 (20.0) | .596 |

| FEV1 (%) | 98.0 (16.6) | 77.2 (19.2) | <.001 |

Values expressed as mean (standard deviation) or by absolute (relative) frequencies, depending on the nature of the variables.

Patients attending smoking cessation clinics are likely to be particularly sensitive to the health effects of tobacco use, and offer an opportunity to improve the diagnosis of COPD. Project 1000-200 provides information on the prevalence of bronchial obstruction and COPD in a population of patients attending a smoking cessation clinic. The results show that (1) it is possible to use smoking cessation clinics to diagnose COPD and (2) that the prevalence of both bronchial obstruction and clinical COPD is higher than described for the general population in Spain.4

In recent years, several initiatives to use smoking cessation clinics for the diagnosis of COPD have been launched.10 Recently, the DIPREPOQ study reported a prevalence of clinical COPD of 28.9% among 252 participants analyzed in accredited smoking cessation units.7 This study involved 8 health centers from 7 Spanish regions, so it may be less representative. Although the aim of the study was to detect patients with COPD, the finding of different spirometry patterns demonstrates that other respiratory diseases can be detected during the subsequent diagnostic process.

More than half of our cohort were women, but individuals with bronchial obstruction were mostly male. Although the latest prevalence studies indicate that there are already regions where the prevalence of COPD is higher in women than in men,4 male sex is still clearly prevalent nationwide. Nonetheless, the disease must nowadays be suspected equally in men and women.11

Most of the cases detected had few symptoms (mMRC 0–1). However, 23.9% of the cases with obstruction had a significant degree of dyspnea, yet did not have a confirmed diagnosis on spirometry. The reasons why symptomatic patients fail to be diagnosed are multidimensional and probably associated with widespread ignorance of the disease among the general public and scant resources available in Primary Care. Thus, promoting public awareness of the disease should be a priority in community medicine.12 Patients with no bronchial obstruction also accounted for 7.1% of symptomatic cases. These data confirm that COPD must always be verified by lung function testing, and that a diagnosis cannot be assumed exclusively on the basis of symptoms.13 Moreover, most of the cases detected had a mild or moderate degree of functional involvement. This finding is particularly interesting because the greatest lung function decline is known to occur at the beginning of the disease, so early identification offers a chance to start treatment and reap long-term benefits.14

In short, Project 1000-200 has shown that patients with COPD can be identified in a smoking cessation clinic. These data should encourage those responsible for these consultations to ensure that all patients have a clinical and spirometric assessment for early detection of COPD.

FundingThis study received an unconditional grant from GlaxoSmithKline Laboratories Spain. The sponsors were not involved in the design or conduct of the study or in the collection or analysis of the data.

Conflict of InterestsJLLC has received honoraria in the past 3 years for lectures, scientific consultancy, clinical trial participation, and writing of papers from (in alphabetical order): AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Esteve, Ferrer, Gebro, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols, Menarini, Novartis, Rovi and Teva. The other authors state that they have no conflict of interests.