Respiratory rehabilitation (RR) has been shown to be effective with a high level of evidence in terms of improving symptoms, exertion capacity, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in patients with COPD and in some patients with diseases other than COPD. According to international guidelines, RR is basically indicated in all patients with chronic respiratory symptoms, and the type of program offered depends on the symptoms themselves. As requested by the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR), we have created this document with the aim to unify the criteria for quality care in RR. The document is organized into sections: indications for RR, evaluation of candidates, program components, characteristics of RR programs and the role of the administration in the implementation of RR. In each section, we have distinguished 5 large disease groups: COPD, chronic respiratory diseases other than COPD with limiting dyspnea, hypersecretory diseases, neuromuscular diseases with respiratory symptoms and patients who are candidates for thoracic surgery for lung resection.

La rehabilitación respiratoria (RR) ha demostrado ser eficaz con un alto nivel de evidencia en términos de mejora de los síntomas, la capacidad de esfuerzo y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS) en los pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva crónica (EPOC) y en algunos pacientes con enfermedades distintas de la EPOC. De acuerdo con las guías internacionales, la RR está indicada fundamentalmente en todo paciente con síntomas respiratorios crónicos. Dependiendo de los mismos se le ofrecerá un tipo u otro de programa. Por encargo de la Sociedad Española de Neumología y Cirugía Torácica (SEPAR) hemos realizado este documento con el objetivo de unificar los criterios de calidad asistencial en RR. El documento esta organizado en 5 apartados que incluyen: las indicaciones de la RR, la evaluación de los candidatos, los componentes de los programas, las características de los programas de RR y el papel de la administración en la implantación de la RR. En cada apartado hemos distinguido 5 grandes grupos de enfermedades: EPOC, enfermedades respiratorias crónicas distintas de la EPOC con disnea limitante (ERCDL), enfermedades hipersecretoras, enfermedades neuromusculares con síntomas respiratorios y pacientes candidatos a cirugía torácica para una resección pulmonar.

Recently, the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) have defined pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) as “an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive intervention for patients with chronic respiratory diseases who are symptomatic and often have decreased daily life activities. Integrated into the individualized treatment of the patient, pulmonary rehabilitation is designed to reduce symptoms, optimize functional status, increase participation, and reduce health care costs through stabilizing or reversing systemic manifestations of the disease. Pulmonary rehabilitation programs involve patient assessment, exercise training, education [including physical therapy], nutritional intervention, and psychosocial support.1”

It can currently be affirmed with a high scientific evidence that PR programs involving muscle training improve dyspnea, exertion capacity, and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)1–4 and in other respiratory diseases other than COPD.2,5,6 These benefits can be observed if the PR is done either in the hospital setting or in patients’ homes.7–17 The evidence available about the effectiveness of PR has led scientific societies and professionals to recommend it as a fundamental treatment.1,2,18–21

Nonetheless, the data available to us, both in our country and in the rest of Europe and North America, show that the implementation of PR is very far from what it should be, considering its effectiveness. Although the information is very limited, there seems to be a very marked geographical imbalance.22,23 In Spain, there are no studies about the distribution and the characteristics of the PR programs or the percentage of patients receiving PR.24 The implementation of this therapy completely depends on the policies of each Spanish autonomous community (provinces).25,26 Some communities, like Catalonia, have established accords with public health-care services to provide PR treatments in both the ambulatory setting and in patient homes.27

Therefore, in order to avoid serious inequalities for accessing PR in our country and to promote quality care for COPD patients as well as those with diseases other than COPD, it is necessary for there to be cooperative action between the health administrations and scientific societies as well as raised consciousness of health-care professionals to promote and guarantee proper and universal implementation of PR. Among the possible actions would be to favor understanding of PR and its inclusion in the health-care programs of the different Spanish provinces and in specific plans for the integral treatment of COPD and other respiratory diseases.

Aware of this situation, the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) has requested the Quality Healthcare Committee of the Society to prepare PR quality standards for patients with chronic respiratory diseases. The aim of this document is to unify the quality criteria for the indications, candidate evaluation, and PR programs and, in addition, to define the role of the administration in the implementation of PR.

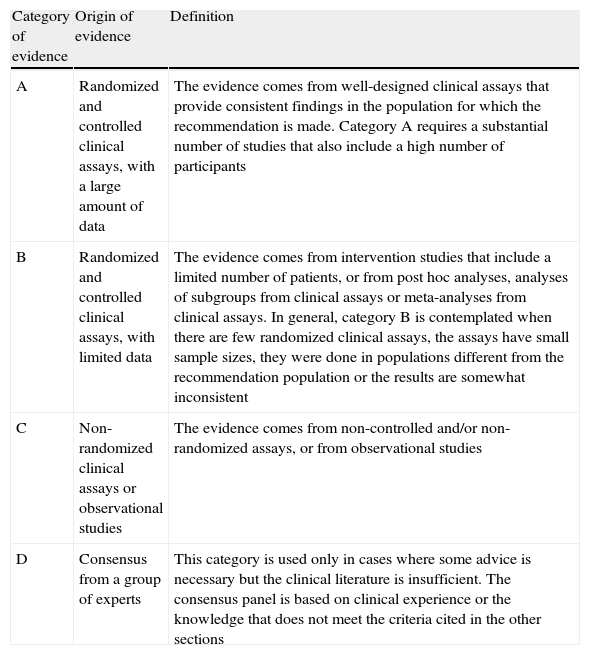

MethodsThe definitions of quality health-care, dimensions of quality, quality criteria, quality indicators, and quality standards have been previously published in the article “Health-Care Quality Standards in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease”.28 Although they are later described in detail, the sections on quality health-care assessment, the accreditation process, the duration and validation of the standards have also been elaborated based on the cited document. Table 1 describes the level of evidence of each recommendation.29

Description of the Levels of Evidence.

| Category of evidence | Origin of evidence | Definition |

| A | Randomized and controlled clinical assays, with a large amount of data | The evidence comes from well-designed clinical assays that provide consistent findings in the population for which the recommendation is made. Category A requires a substantial number of studies that also include a high number of participants |

| B | Randomized and controlled clinical assays, with limited data | The evidence comes from intervention studies that include a limited number of patients, or from post hoc analyses, analyses of subgroups from clinical assays or meta-analyses from clinical assays. In general, category B is contemplated when there are few randomized clinical assays, the assays have small sample sizes, they were done in populations different from the recommendation population or the results are somewhat inconsistent |

| C | Non-randomized clinical assays or observational studies | The evidence comes from non-controlled and/or non-randomized assays, or from observational studies |

| D | Consensus from a group of experts | This category is used only in cases where some advice is necessary but the clinical literature is insufficient. The consensus panel is based on clinical experience or the knowledge that does not meet the criteria cited in the other sections |

Taken from Lawrence et al.29

The standards for quality PR in COPD and in diseases other than COPD have been developed under the tutelage and auspices of the Quality Healthcare Committee of SEPAR. A group of professionals related with PR, including 3 pulmonologists, a rehabilitation physician and 2 physical therapists from the area of pulmonology, have created this document after evaluating the recommendations based on scientific evidence about the evaluation of the patient, indications, components, and the characteristics of PR programs. The choice of the indicators of each section has been decided on by consensus of the entire group after careful review of international guidelines (ATS and ERS) and bibliographic reviews. We should also mention that we have incorporated original indicators, which we have considered important and fundamental.

In an initial phase, each section of the document was developed by 2 authors of the group working independently. After the section was reviewed by all the authors, a second draft was prepared and the final document was put together with the consecutive revisions of the entire group, until consensus was reached.

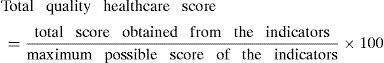

Assessment of Quality HealthcareSimilar to the standards for quality healthcare in COPD,28 this present PR document incorporates specific indicators that accompany each quality criterion and serve as an instrument for measurement. However, unlike in COPD, on this occasion we have not identified key indicators or standards of quality healthcare that, in the opinion of this workgroup, seriously compromised the overall care quality. In total, there are 35 indicators of quality care, and 10 are included in the administrative block. The result obtained in each specific indicator will be expressed as a percentage. An indicator is considered acceptable (AI) when the proportion of compliance is equal to or greater than 60%. Outside of these margins, it is considered deficient (DI). As mentioned in the previous article,28 these percentages are arbitrary and need to be validated.

According to the value of the indicators, the score assigned will be:

- •

Deficient indicator (DI): result <60%=0 points

- •

Acceptable indicator (AI): result ≥60%=2 points

The total score will be relativized to the maximum possible score, according to the final number of applicable standards, in accordance with the following formula:

The final total classification of healthcare quality will be catalogued in the following manner:

- •

Deficient overall healthcare quality (DHQ): total score less than 50% of the maximum possible applicable value

- •

Sufficient overall healthcare quality (SHQ): total score between 50% and 84% of the maximum possible applicable value according to each case

- •

Excellent overall healthcare quality (EHQ): when the total score is equal to or greater than 85% of the maximum possible applicable value in each case

The score obtained in the 10 indicators corresponding with the administrative block will not be considered to obtain the overall classification of healthcare quality, and therefore will not influence the final accreditation process. However, this should be included in the final accreditation report as it is important for the objective of improving PR healthcare quality.

Accreditation ProcessAs stated in the previous article,28 the corresponding organism will designate a qualified auditing team that will review compliance with quality standards. In cases where the assessment is negative, the auditing and accreditation commission will be able to request a plan of action and timeframe for compliance from the center or unit that is audited.

Duration and Validation of the StandardsThe workgroup, in accordance with the previous article,28 considers that standards for quality should be periodically reviewed depending on the scientific evidence (possibly every 3–4 years) and modified if necessary.

Structure of the Standards for Quality Healthcare in Pulmonary RehabilitationThe standards for quality have been structured into 5 sections for the 5 large disease groups:

- 1.

COPD.

- 2.

Other chronic respiratory diseases with limiting dyspnea (CRDLD), such as pulmonary arterial hypertension, interstitial diseases, asthma, bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis with exertion limitations, patients’ who are candidates for lung transplantation or volume reduction, etc.

- 3.

Hypersecretory diseases, fundamentally bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis if they do not present with dyspnea or reduced exercise capacity.

- 4.

Neuromuscular diseases with respiratory symptoms, fundamentally inefficient cough.

- 5.

Patients who are candidates for thoracic surgery for lung resection.

In most PR standards related with COPD, either in the benefits of PR or its components, there is a high-moderate level of evidence in the literature. Nonetheless, regarding respiratory physiotherapy as one of the components of PR, fundamentally some specific techniques both in COPD as in other respiratory diseases, there is little evidence and the degree of recommendation is often only based on the opinion of experts (level D of evidence).1,2,21 In spite of this, this workgroup has considered it important to include it, given that in clinical practice its usefulness has been demonstrated and, in our opinion, the weak evidence is a consequence of the few well-designed studies in the literature.

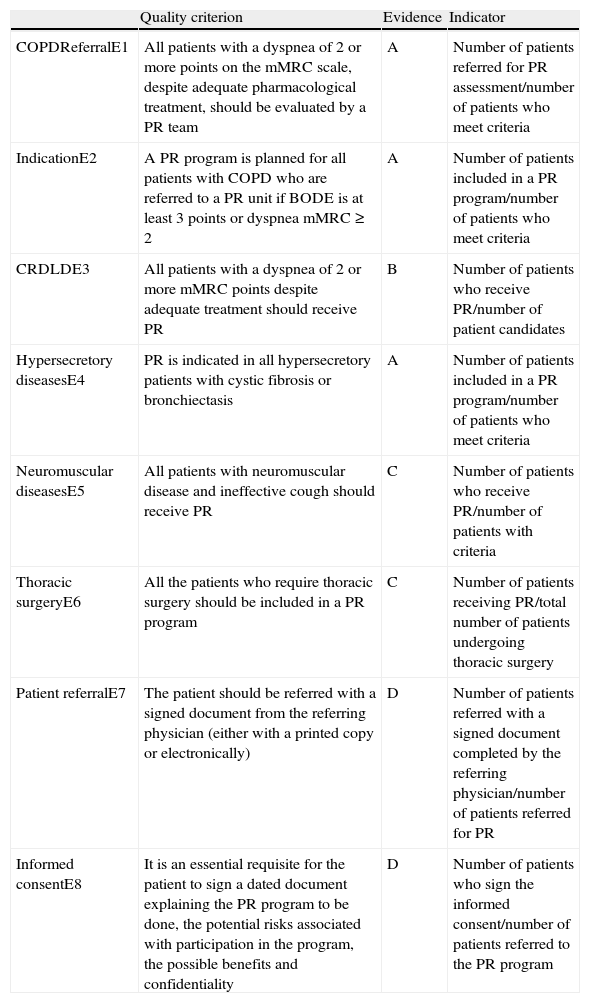

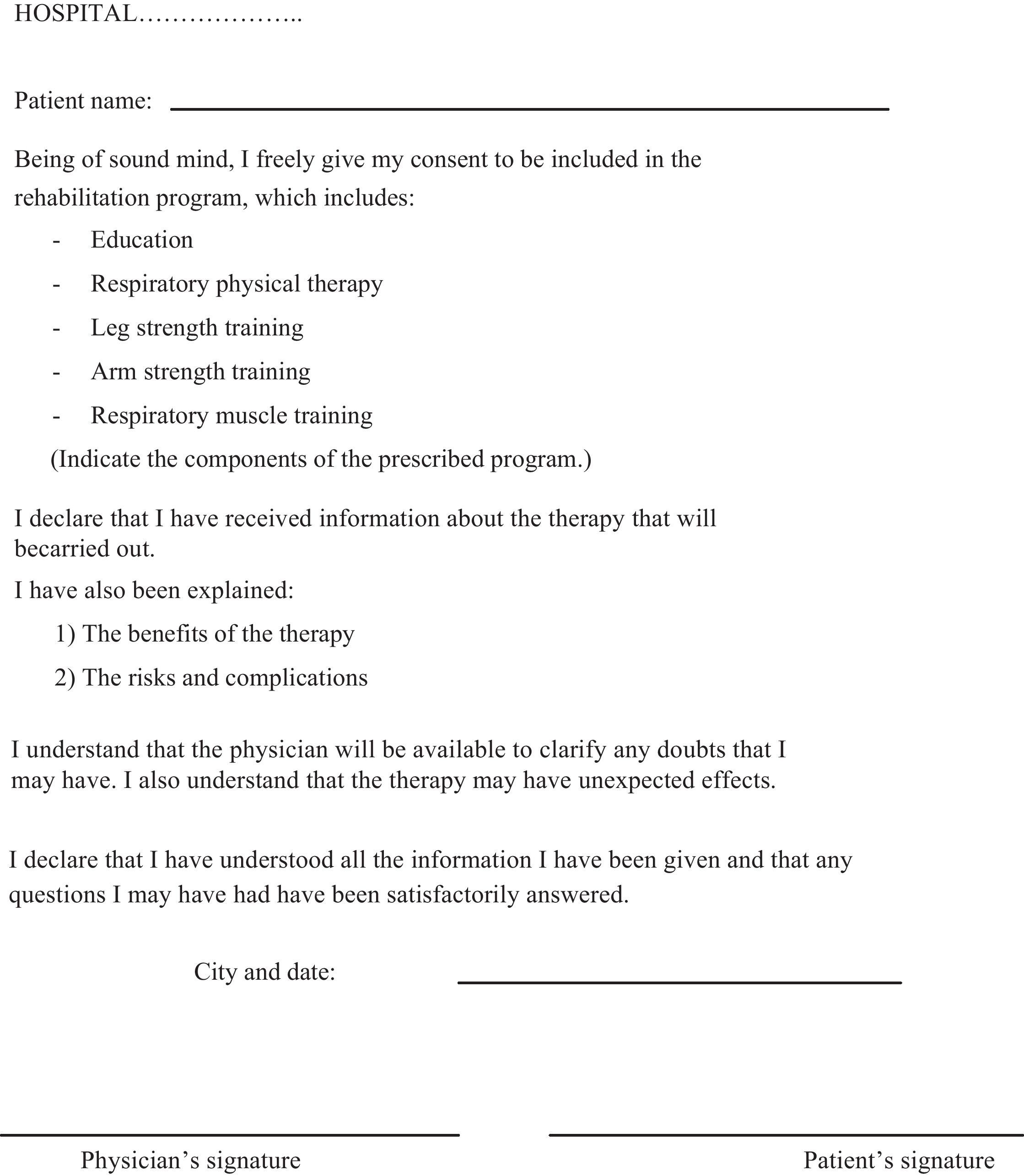

Indications for Pulmonary Rehabilitation (Table 2)In this section, we want to underline several points, as they are new and important:

- (a)

All the patients require a referral document that has been filled out and signed by the referring physician.

- (b)

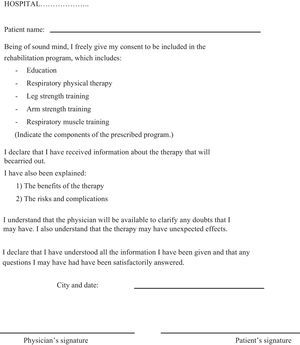

All the patients’ who participate in any of the PR programs should sign an informed consent form, after exactly understanding what the program is and why it has been proposed, its benefits and the potential adverse effects (Appendix A, annex 1 proposes a model).

- (c)

Patients with COPD should be assessed whether the indication of a complete PR program is adequate or not according to the criteria outlined in the table.

Standards for Quality Care in Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR): Indications for PR.

| Quality criterion | Evidence | Indicator | |

| COPDReferralE1 | All patients with a dyspnea of 2 or more points on the mMRC scale, despite adequate pharmacological treatment, should be evaluated by a PR team | A | Number of patients referred for PR assessment/number of patients who meet criteria |

| IndicationE2 | A PR program is planned for all patients with COPD who are referred to a PR unit if BODE is at least 3 points or dyspnea mMRC≥2 | A | Number of patients included in a PR program/number of patients who meet criteria |

| CRDLDE3 | All patients with a dyspnea of 2 or more mMRC points despite adequate treatment should receive PR | B | Number of patients who receive PR/number of patient candidates |

| Hypersecretory diseasesE4 | PR is indicated in all hypersecretory patients with cystic fibrosis or bronchiectasis | A | Number of patients included in a PR program/number of patients who meet criteria |

| Neuromuscular diseasesE5 | All patients with neuromuscular disease and ineffective cough should receive PR | C | Number of patients who receive PR/number of patients with criteria |

| Thoracic surgeryE6 | All the patients who require thoracic surgery should be included in a PR program | C | Number of patients receiving PR/total number of patients undergoing thoracic surgery |

| Patient referralE7 | The patient should be referred with a signed document from the referring physician (either with a printed copy or electronically) | D | Number of patients referred with a signed document completed by the referring physician/number of patients referred for PR |

| Informed consentE8 | It is an essential requisite for the patient to sign a dated document explaining the PR program to be done, the potential risks associated with participation in the program, the possible benefits and confidentiality | D | Number of patients who sign the informed consent/number of patients referred to the PR program |

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council scale. CRDLD, chronic respiratory diseases with limiting dyspnea.

The indication of PR has a moderate-high level of evidence, depending on the disease. The need for the referral document and informed consent are based on a recommendation with a level of evidence D30 (Table 2).

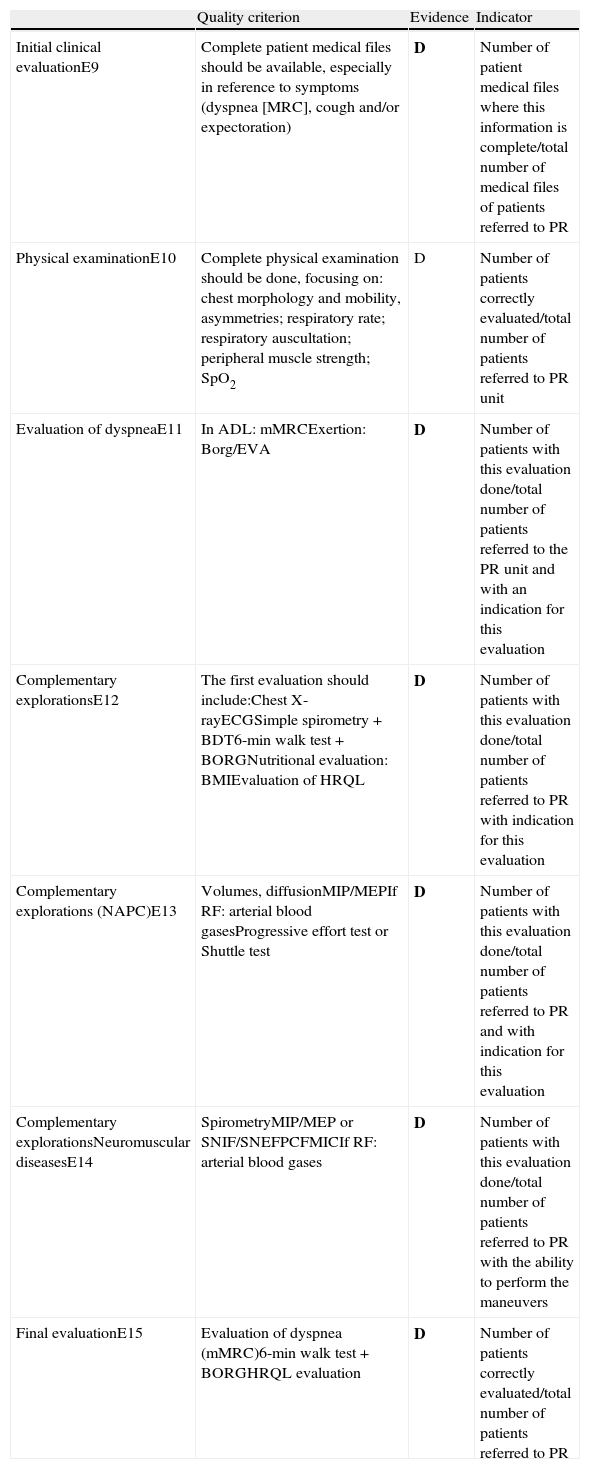

Patient Evaluation (Table 3)The clinical and physical exploration and some of the complementary explorations are the same for any of the 5 groups of pathologies. Nevertheless, there are explorations, fundamentally lung function tests like respiratory pressure or peak flow during cough, that are specific for neuromuscular patients, or the determination of static lung volumes and diffusion capacity that is necessary in patients with COPD (Table 3).

Quality Standards in Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR): Patient Evaluation.

| Quality criterion | Evidence | Indicator | |

| Initial clinical evaluationE9 | Complete patient medical files should be available, especially in reference to symptoms (dyspnea [MRC], cough and/or expectoration) | D | Number of patient medical files where this information is complete/total number of medical files of patients referred to PR |

| Physical examinationE10 | Complete physical examination should be done, focusing on: chest morphology and mobility, asymmetries; respiratory rate; respiratory auscultation; peripheral muscle strength; SpO2 | D | Number of patients correctly evaluated/total number of patients referred to PR unit |

| Evaluation of dyspneaE11 | In ADL: mMRCExertion: Borg/EVA | D | Number of patients with this evaluation done/total number of patients referred to the PR unit and with an indication for this evaluation |

| Complementary explorationsE12 | The first evaluation should include:Chest X-rayECGSimple spirometry+BDT6-min walk test+BORGNutritional evaluation: BMIEvaluation of HRQL | D | Number of patients with this evaluation done/total number of patients referred to PR with indication for this evaluation |

| Complementary explorations (NAPC)E13 | Volumes, diffusionMIP/MEPIf RF: arterial blood gasesProgressive effort test or Shuttle test | D | Number of patients with this evaluation done/total number of patients referred to PR and with indication for this evaluation |

| Complementary explorationsNeuromuscular diseasesE14 | SpirometryMIP/MEP or SNIF/SNEFPCFMICIf RF: arterial blood gases | D | Number of patients with this evaluation done/total number of patients referred to PR with the ability to perform the maneuvers |

| Final evaluationE15 | Evaluation of dyspnea (mMRC)6-min walk test+BORGHRQL evaluation | D | Number of patients correctly evaluated/total number of patients referred to PR |

mMRC, modified Medical Research Council scale; SpO2, oxyhemoglobin saturation; ADL, activities of daily life; AVS, analogue visual scale; NAPC, standard for quality not applicable in primary care; BDT, bronchodilator test; BMI, body mass index; HRQL, health-related quality of life; MIP, maximum inspiratory pressure; MEP, maximum expiratory pressure; RF, respiratory failure; SNIF, SNEF, maximum nasal inspiratory and expiratory pressure; PCF, peak cough flow; MIC, maximum inspiratory capacity.

It is fundamental to carry out exertion tests in patients who are candidates for a PR program that includes muscle training, and in the best instance such would be progressive. However, when this is not possible, a field test is sufficient, like the 6-min walk test31 or the Shuttle walking test.32 This latter test is able to estimate the maximum load in watts of the distance walked by applying a simple formula. This makes it easier to calculate the load to apply during training with the cycle ergometer.33 In cases where these tests are not available, the intensity of the aerobic training can be established according to a scale of symptoms (Borg scale). A level of activity is recommended to cause in the patient a sensation of dyspnea and/or tiredness that ranges between 3 (moderate) and 5 (severe).30

It is recommended (although not essential) to measure the health-related quality of life. In this case, a specific questionnaire is recommended, such as the St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)34 or the chronic respiratory disease questionnaire (CRQ), either with an interviewer34 or self-administered,35 and a generic questionnaire such as the SF36 health questionnaire or the reduced SF12 version.34 In recent months, it has been demonstrated that the Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Assessment Test (CAT) could be a very useful tool due to its simplicity; also, it is a questionnaire that is sensitive to change and equal to more complex measurements, like SGRQ or CRQ.36

It is desirable for all the patients to have a clinical report at the end of the program specifying the treatment done and the response to said treatment, as well as recommendations for after discharge.

In this section, the grade/degree of recommendation is based on the opinion of experts (D).

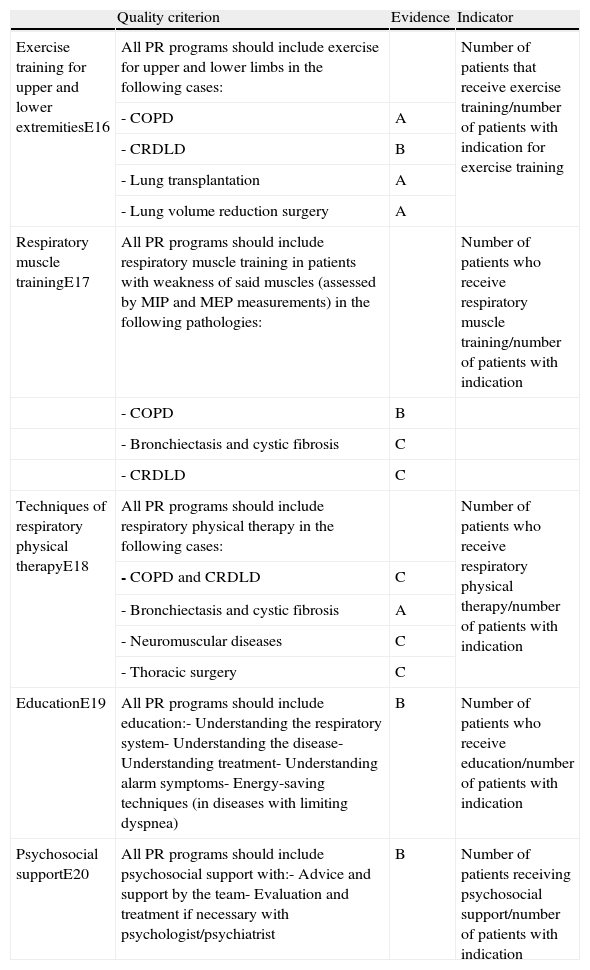

Components of the Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programs (Table 4)It is important to remark that the scientific evidence of PR components has been basically established in COPD (Table 4).

Quality Standards in Pulmonary Rehabilitation (RR): Components of the Programs.

| Quality criterion | Evidence | Indicator | |

| Exercise training for upper and lower extremitiesE16 | All PR programs should include exercise for upper and lower limbs in the following cases: | Number of patients that receive exercise training/number of patients with indication for exercise training | |

| - COPD | A | ||

| - CRDLD | B | ||

| - Lung transplantation | A | ||

| - Lung volume reduction surgery | A | ||

| Respiratory muscle trainingE17 | All PR programs should include respiratory muscle training in patients with weakness of said muscles (assessed by MIP and MEP measurements) in the following pathologies: | Number of patients who receive respiratory muscle training/number of patients with indication | |

| - COPD | B | ||

| - Bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis | C | ||

| - CRDLD | C | ||

| Techniques of respiratory physical therapyE18 | All PR programs should include respiratory physical therapy in the following cases: | Number of patients who receive respiratory physical therapy/number of patients with indication | |

| - COPD and CRDLD | C | ||

| - Bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis | A | ||

| - Neuromuscular diseases | C | ||

| - Thoracic surgery | C | ||

| EducationE19 | All PR programs should include education:- Understanding the respiratory system- Understanding the disease- Understanding treatment- Understanding alarm symptoms- Energy-saving techniques (in diseases with limiting dyspnea) | B | Number of patients who receive education/number of patients with indication |

| Psychosocial supportE20 | All PR programs should include psychosocial support with:- Advice and support by the team- Evaluation and treatment if necessary with psychologist/psychiatrist | B | Number of patients receiving psychosocial support/number of patients with indication |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRDLD, chronic respiratory diseases with limiting dyspnea; MIP, maximum inspiratory pressure; MEP, maximum expiratory pressure.

Muscle training is the most effective component of PR, with a high level of evidence and recommendation. Contrarily, specific training of respiratory muscles has a moderate level of evidence and recommendation. The most widely accepted training method is aerobic or endurance training, although it is recommended to combine this with strength training.

PR programs and their components should contemplate 3 fundamental characteristics: duration, frequency, and intensity.37

Education should include knowledge about the disease, treatment management, and recognizing signs of alarm for exacerbation.

Respiratory physical therapy has a moderate-high level of evidence only in hypersecretory diseases; nonetheless, the degree of recommendation varies from some techniques to others.21

Psychosocial support has a controversial role, with a moderate level of scientific evidence. In general, it is considered that, with the support of the PR team and without the specific intervention of psychologists or psychiatrists, there are beneficial effects as demonstrated in several studies.1,2,38 Only in the cases with the most severe symptoms is it necessary for the patient to be referred to a psychiatrist.

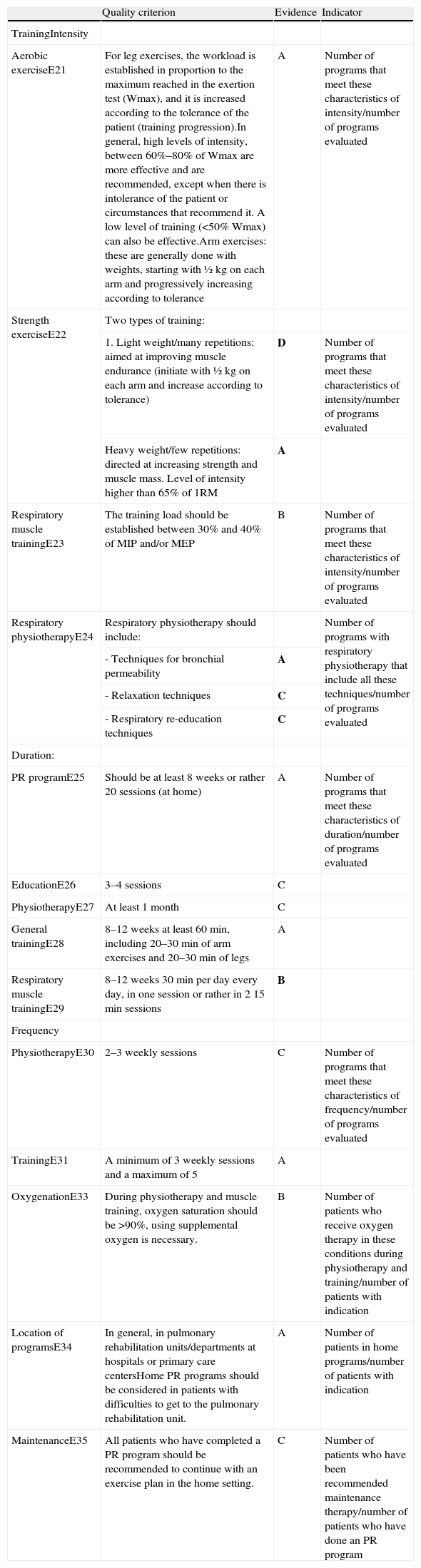

Characteristics of Pulmonary Rehabilitation Programs (Table 5)Currently, it can be affirmed that treatment intensity, duration, frequency, and location of PR programs are well established, with a high level of evidence and recommendation. A minimum duration of PR programs of 8 weeks or 20 sessions (3–5 sessions per week) is considered adequate. Exercise is based on an intensity of between 60% and 80% of the maximum exertion capacity of the patient. It would be optimal to measure this with the progressive exertion test or the Shuttle walking test. If this is not possible, the exercise intensity can be established based on the symptoms (dyspnea and leg discomfort) experienced while exercising, according to the Borg scale, as we have explained in the “Patient evaluation” section (Table 5).

Quality Standards for Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR): Program Characteristics.

| Quality criterion | Evidence | Indicator | |

| TrainingIntensity | |||

| Aerobic exerciseE21 | For leg exercises, the workload is established in proportion to the maximum reached in the exertion test (Wmax), and it is increased according to the tolerance of the patient (training progression).In general, high levels of intensity, between 60%–80% of Wmax are more effective and are recommended, except when there is intolerance of the patient or circumstances that recommend it. A low level of training (<50% Wmax) can also be effective.Arm exercises: these are generally done with weights, starting with ½kg on each arm and progressively increasing according to tolerance | A | Number of programs that meet these characteristics of intensity/number of programs evaluated |

| Strength exerciseE22 | Two types of training: | ||

| 1. Light weight/many repetitions: aimed at improving muscle endurance (initiate with ½kg on each arm and increase according to tolerance) | D | Number of programs that meet these characteristics of intensity/number of programs evaluated | |

| Heavy weight/few repetitions: directed at increasing strength and muscle mass. Level of intensity higher than 65% of 1RM | A | ||

| Respiratory muscle trainingE23 | The training load should be established between 30% and 40% of MIP and/or MEP | B | Number of programs that meet these characteristics of intensity/number of programs evaluated |

| Respiratory physiotherapyE24 | Respiratory physiotherapy should include: | Number of programs with respiratory physiotherapy that include all these techniques/number of programs evaluated | |

| - Techniques for bronchial permeability | A | ||

| - Relaxation techniques | C | ||

| - Respiratory re-education techniques | C | ||

| Duration: | |||

| PR programE25 | Should be at least 8 weeks or rather 20 sessions (at home) | A | Number of programs that meet these characteristics of duration/number of programs evaluated |

| EducationE26 | 3–4 sessions | C | |

| PhysiotherapyE27 | At least 1 month | C | |

| General trainingE28 | 8–12 weeks at least 60min, including 20–30min of arm exercises and 20–30min of legs | A | |

| Respiratory muscle trainingE29 | 8–12 weeks 30min per day every day, in one session or rather in 2 15min sessions | B | |

| Frequency | |||

| PhysiotherapyE30 | 2–3 weekly sessions | C | Number of programs that meet these characteristics of frequency/number of programs evaluated |

| TrainingE31 | A minimum of 3 weekly sessions and a maximum of 5 | A | |

| OxygenationE33 | During physiotherapy and muscle training, oxygen saturation should be >90%, using supplemental oxygen is necessary. | B | Number of patients who receive oxygen therapy in these conditions during physiotherapy and training/number of patients with indication |

| Location of programsE34 | In general, in pulmonary rehabilitation units/departments at hospitals or primary care centersHome PR programs should be considered in patients with difficulties to get to the pulmonary rehabilitation unit. | A | Number of patients in home programs/number of patients with indication |

| MaintenanceE35 | All patients who have completed a PR program should be recommended to continue with an exercise plan in the home setting. | C | Number of patients who have been recommended maintenance therapy/number of patients who have done an PR program |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CRDLD, chronic respiratory disease with limiting dyspnea; Wmax, maximum effort in a progressive effort test; Test 1RM, one maximum repetition test.

There is not sufficient information about the use of oxygen while performing the programs or of the possible techniques or strategies for maintaining the benefits, possibly due to the small number of studies published about these 2 aspects.1,2

Home PR programs would be indicated in patients with COPD or CRDLD with impaired movement. The therapy includes respiratory physical therapy techniques, arm training with weights, and leg training with a cycle ergometer or walking.

Home PR programs are also indicated in patients with neuromuscular diseases with impaired mobility who need secretion drainage.

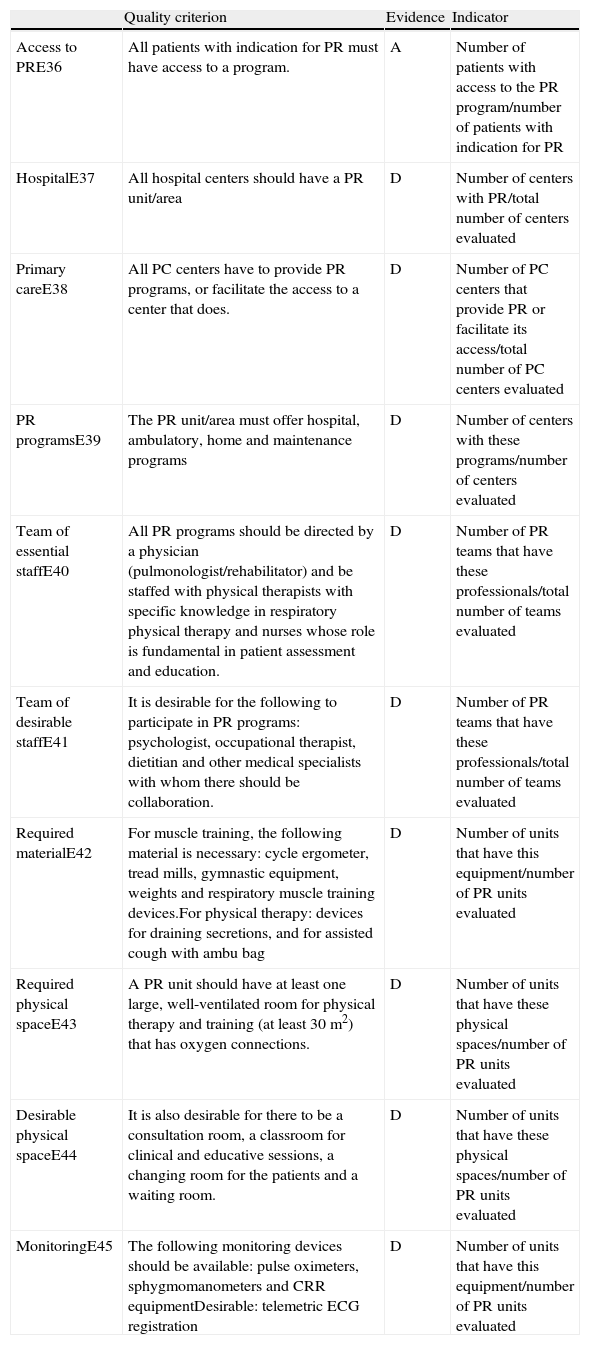

Standards for Quality PR Care That the Health Administration Should Comply With (Table 6)In this section, except for the possibility of PR being made available to all patients who need it, the remaining standards are only based on the opinion of experts because they are not defined in any previous documents. As such, the workgroup considers that quality healthcare would involve the availability of multidisciplinary PR in all hospital centers, made up of at least physical therapists and specialized nurses and a directing pulmonologist or rehabilitator. The presence on the team of a dietitian, an occupational therapist and a psychologist would also be desirable. The PR units should have the necessary space and material in order to properly fulfill the programs, which should be offered in ambulatory, home, and maintenance regimes (Table 6).

Standards for Quality Care in Pulmonary Rehabilitation (PR) That the Public Healthcare Administration Should Comply With.

| Quality criterion | Evidence | Indicator | |

| Access to PRE36 | All patients with indication for PR must have access to a program. | A | Number of patients with access to the PR program/number of patients with indication for PR |

| HospitalE37 | All hospital centers should have a PR unit/area | D | Number of centers with PR/total number of centers evaluated |

| Primary careE38 | All PC centers have to provide PR programs, or facilitate the access to a center that does. | D | Number of PC centers that provide PR or facilitate its access/total number of PC centers evaluated |

| PR programsE39 | The PR unit/area must offer hospital, ambulatory, home and maintenance programs | D | Number of centers with these programs/number of centers evaluated |

| Team of essential staffE40 | All PR programs should be directed by a physician (pulmonologist/rehabilitator) and be staffed with physical therapists with specific knowledge in respiratory physical therapy and nurses whose role is fundamental in patient assessment and education. | D | Number of PR teams that have these professionals/total number of teams evaluated |

| Team of desirable staffE41 | It is desirable for the following to participate in PR programs: psychologist, occupational therapist, dietitian and other medical specialists with whom there should be collaboration. | D | Number of PR teams that have these professionals/total number of teams evaluated |

| Required materialE42 | For muscle training, the following material is necessary: cycle ergometer, tread mills, gymnastic equipment, weights and respiratory muscle training devices.For physical therapy: devices for draining secretions, and for assisted cough with ambu bag | D | Number of units that have this equipment/number of PR units evaluated |

| Required physical spaceE43 | A PR unit should have at least one large, well-ventilated room for physical therapy and training (at least 30 m2) that has oxygen connections. | D | Number of units that have these physical spaces/number of PR units evaluated |

| Desirable physical spaceE44 | It is also desirable for there to be a consultation room, a classroom for clinical and educative sessions, a changing room for the patients and a waiting room. | D | Number of units that have these physical spaces/number of PR units evaluated |

| MonitoringE45 | The following monitoring devices should be available: pulse oximeters, sphygmomanometers and CRR equipmentDesirable: telemetric ECG registration | D | Number of units that have this equipment/number of PR units evaluated |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PC, primary care; CRR, cardiorespiratory reanimation; ECG, electrocardiogram.

PR has been demonstrated to improve symptoms, exertion capacity, and HRQL, both in COPD patients as well as in those with diseases other than COPD. Nevertheless, despite the high level of evidence of these benefits, the implementation of PR in our country is very limited and unequal. In the Spanish territory, there is an extensive variety of programs, and they often do not offer the minimums recommended by international guidelines, nor do they have specialized personnel. This situation has led us to propose a document that establishes quality healthcare standards in PR, with the objective to foster good clinical practice in this therapeutic area that is uniform and conforms the different programs to the best scientific evidence. The document also poses developing specific indicators that allow the care quality of PR in our setting to be evaluated in a homogenous manner.

This document reflects how a pulmonary rehabilitation unit or center should be organized and what requirements should be met in terms of resources (both human as well as material). It proposes indicators for quality health care, contemplating the indications, components and characteristics of the programs, and the evaluation measures. We have determined that all the indicators have the same value, although we are aware of the fact that some are more easily implemented than others, and that some are more essential than others for the final score. The final quality care classification that is proposed goes from deficient to excellent, with enough of a margin so that an area, unit or center may have a high overall classification, without meeting all the quality indicators.

Furthermore, the document impels the public health administration to make a commitment to quality care in PR and make multidisciplinary PR units accessible, provide professionals with specialized PR training, and foster the creation of units that comply with the adequate space and material requirements in order to offer good quality healthcare.

As we write this document, we are aware that there is still a long way to go in order to reach all the proposed objectives. Nonetheless, considering that there are currently few centers where PR is offered and many people are interested in its implementation, having quality care guidelines in place may favor the development of PR units and centers in our country. Another point to emphasize in this document is extending the PR services to patients other than those with COPD. All PR guidelines and reviews discuss non-COPD respiratory diseases, but this aspect is underdeveloped, and the proof is the limited literature that exists in this field.

It is also important to underline that there are more and more patients with diseases that are not specifically respiratory disorders, such as neuromuscular issues and obesity, who are treated by respiratory disease professionals. The result is that pulmonologists are becoming specialists who lead multidisciplinary treatments, where PR plays such an important role.

Finally, we want to emphasize that the proposals found in the “National Healthcare Plan's Strategy for COPD” are similar to what is proposed in these present standards, although they obviously are directed at patients with COPD.

ConclusionPR is a therapy that has been shown to be effective with a high level of evidence, although its implementation in our country is very low. The standardization of indicators for quality PR care is fundamental in order for this treatment to be extensively and effectively established.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors declare having no conflict of interests.

The authors would like to thank the SEPAR Quality Healthcare Committee and, specifically, Dr. Inmaculada Alfageme, for the trust she has shown us by assigning us this document.

Please cite this article as: Güell MR, et al. Estándares de calidad asistencial en rehabilitación respiratoria en pacientes con enfermedad pulmonar crónica. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48:396–404.