Well-coordinated multidisciplinary teams are essential for better tuberculosis (TB) control. Our objective was to evaluate the impact of Spanish Society of Pneumology (SEPAR) accreditation of TB Units (TBU) and to determine differences between the accredited and non-accredited centers.

Material and methods. DesignObservational descriptive study based on a self-administered survey from October 2014 to February 2018 completed by 139 heads of respiratory medicine departments collected by SEPAR, before and after TBU accreditation.

Variablesdemographic, epidemiological and contact tracing variables, among others. Analysis: basic descriptive analysis, and calculation of medians for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. The variables were compared using the Chi-squared test and logistic regression.

ResultsThe response rate was 54.7% and 43.2% in the pre- and post-TBU accreditation period, respectively. No differences were observed in the care and coordination variables between the pre- and post-accreditation survey, nor in the organization when only accredited centers were analyzed. When we compared the accredited and non-accredited centers, significant differences were detected in the collection of the final conclusion, management of resistance, coordination with other departments, contact tracing, and directly observed treatment.

ConclusionsThe approach of different professionals with regard to TB has been addressed. Positive aspects and areas for improvement have been detected, and better results were observed in the accredited versus non-accredited centers. A closer supervision of TBUs is necessary to improve their effectiveness.

Un buen control de la tuberculosis (TB) requiere disponer de personal multidisciplinario bien coordinado. El objetivo fue evaluar el impacto de la acreditación de unidades de TB (UTB) fomentada por la Sociedad Española de Neumología (SEPAR) y ver las diferencias entre los centros que se acreditaron y los que no.

Material y métodos. DiseñoEstudio observacional descriptivo basado en una encuesta autoadministrada entre octubre de 2014 y febrero de 2018 a 139 responsables de neumología registrados por SEPAR, antes y después de la acreditación.

Variablesdemográficas, epidemiológicas y sobre estudio de contactos, entre otras. Análisis: descriptiva básica, cálculo de medianas para variables continuas y proporciones para categóricas. Se compararon las variables mediante el test chi-cuadrado y regresión logística.

ResultadosLa tasa de respuesta fue del 54,7 y del 43,2% en el período pre- y postacreditación de UTB, respectivamente. No se observaron cambios en los diferentes ámbitos de atención y coordinación entre la encuesta pre- y postacreditación, ni tampoco en la organización, al analizar los centros acreditados. Al comparar los centros que se acreditaron con los que no, se detectaron diferencias significativas con relación a recogida de conclusión final, manejo de resistencias, coordinación con otros servicios, estudios de contactos o tratamiento directamente observado.

ConclusionesSe ha objetivado cómo abordan la TB diferentes profesionales, se han detectado aspectos positivos y otros mejorables, y se han observando indicadores de mejor funcionamiento en los centros que se acreditaron frente a los que no lo hicieron. Se precisa una supervisión cercana de las UTB para mejorar su efectividad.

One of the key factors in the proper control of tuberculosis (TB), aside from early detection and careful case management, is the availability of specialized staff and good coordination between the various levels. Good control requires not only medical experts, but also adequate numbers of specialized nursing staff, and well-structured and properly organized departments managed by experienced personnel.1–4 In countries where the incidence of TB is low, such as Spain, which has many more primary care physicians (PCPs) than TB patients, TB care and contact tracing should be centralized in specialized units.5 The framework document for the elimination of TB in low-incidence countries stresses the importance of a central coordination team, specialized units for the diagnosis and treatment of TB, and the appropriate level of centralization.5

In their efforts to improve TB control, the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) has promoted the accreditation of tuberculosis units (TBU) dedicated to the treatment, monitoring and prevention of the disease. Although the number of cases has fallen significantly, TB continues to be of clinical importance. It is often difficult to manage, and treatment can be complicated by the presence of forms that are resistant to the most effective drugs. As such, in addition to basic units, we also need expert, specialized units that can advise and manage complex treatments, perform contact tracing, and coordinate with other specialties or levels of care. One of the aims of SEPAR is to support the creation and subsequent accreditation of functional, multidisciplinary TBUs, seeking to unite specialties, professionals, and official bodies involved in the management of this disease.6,7

Awareness of which specialists are responsible for diagnosis, treatment, and contact tracing in patients with pulmonary and extrapulmonary TB and the coordination among the various healthcare strata could help design strategies that will improve the organization of TBUs. This would be an important step forward in the control of TB in Spain.

The aim of this study, therefore, was to characterize the organization of pulmonology departments and professionals working in TB control in Spain before and after the accreditation of TBUs by SEPAR, and to analyze the effectiveness of this initiative.

Materials and MethodsDesign and PeriodThis was a descriptive, cross-sectional, observational, population-based study performed before and after accreditation of specialist care units in Spain between October 1, 2014 and December 31, 2016 and January 1, 2017 and February 28, 2018.

ScopePulmonology departments in Spanish hospitals responded to a self-administered online questionnaire that was sent to the heads of SEPAR-registered pulmonology departments or sections (N = 139). The questionnaire was administered before and after TBU accreditation. SEPAR investigators sent 3 emails inviting respondents to complete the pre-accreditation questionnaire and 3 more for the post-accreditation questionnaire, and those who could not be contacted by email were contacted by telephone. In some cases, the pulmonology department or section heads forwarded the questionnaire to other departments involved in the care of TB.

The initiative consisted of offering SEPAR accreditation to any TB care unit that requested it, providing they met a series of pre-established criteria.6 Twenty-six TBUs in total have been accredited since 2015, classified according to their complexity as basic, specialized, or specialized units for highly complex patients. The accreditation criteria and requirements for each of these categories were classified according to the following strategic lines and objectives: TB care, technical and human resources, availability of a mycobacteria laboratory, ability to perform contact tracing, training, and research activity.6

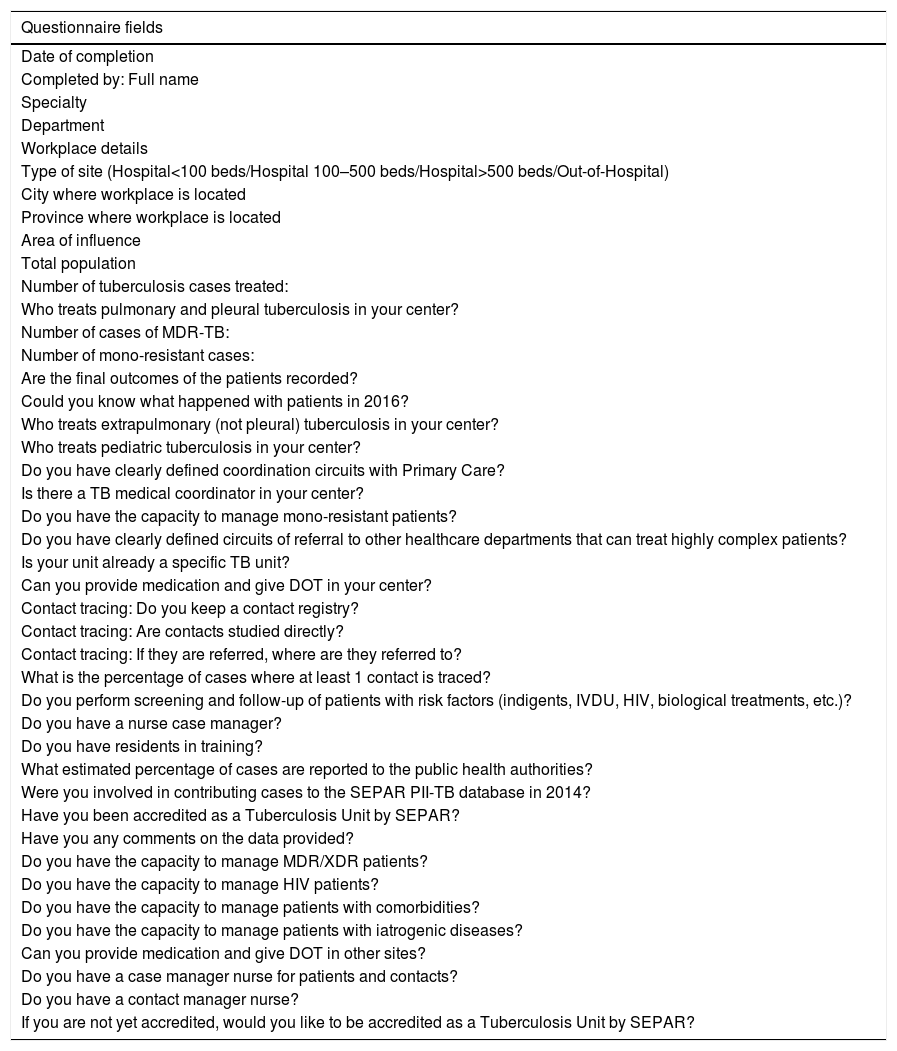

Variables and Sources of InformationThe information was obtained from a specifically designed questionnaire (Appendix A), which was developed taking into account the criteria for SEPAR TBU accreditation. The respondents provided the following variables: demographic (specialty, work center, type of center, city, state, area of influence, and autonomous community), epidemiological (total number of TB cases seen/year, number of multiresistant and monoresistant cases, and final therapeutic outcome), specialist responsible for the treatment of pulmonary, extrapulmonary, and pediatric TB (pulmonologist, internist, infectious disease specialist, pediatrician, others), existence of a TB medical coordinator, coordination with primary care (PC) and other referral routes, existence of a specific TB unit, presence of TB nurse case managers and resident doctors, public health reporting, possibility of administering directly observed treatment (DOT), participation in contact registries and contact tracing, and specialist responsible for this activity (PC, pulmonology, internal medicine, infectious diseases, preventive medicine), screening for latent TB infection in patients with risk factors, participation in the Integrated Research Program In Tuberculosis (PII-TB) and SEPAR TBU accreditation schemes.

Definitions- -

TB medical coordinator: contact person responsible for the coordination and collaboration among pulmonologist and other specialists, and nursing staff.6

- -

TB nurse case manager: TB nursing coordinator promoting organization, coordination, and communication, within and outside the TBU. The nurse case manager liaises between the various actors involved in the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of both active and latent TB infection, and can also centralize all information regarding TB cases and contacts.

- -

Patient with risk factors: includes individuals who have had recent contact with TB patients or medical conditions or behaviors that weaken the immune system.8

A descriptive analysis was performed of the variables before and after accreditation. Questionnaires from accredited and non-accredited centers were compared, using the most recent questionnaire submitted if the center completed both. Medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were calculated for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Categorical variables were compared at a univariate level using the Chi-square or Fisher's exact test if the Chi-square criteria were not met, taking a p value<0.05 as statistically significant. We calculated the factors associated with SEPAR accreditation by performing a logistic regression analysis to compare accredited vs non-accredited centers. As a measure of association, we used the odds ratio (OR), with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and a value of statistical significance of p<0.05. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test was used to determine the goodness of fit of the model.

Ethical ConsiderationsAll data were handled in a strictly confidential manner at all times, following the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki,9 the Spanish Data Protection Law 15/199910 and the European Union General Data Protection Regulation no. 2016/679.11 The project was approved by Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Institut Municipal d’Assistència Sanitària, number 2013/5389/I.

ResultsOf the 139 pulmonology departments or sections contacted in Spain, 76 (54.7%) completed the pre-accreditation questionnaire administered between 2014 and 2016, and 60 (43.2%) completed the post-accreditation questionnaire between 2017 and 2018. A total of 93 centers completed at least one questionnaire, and 43 completed both.

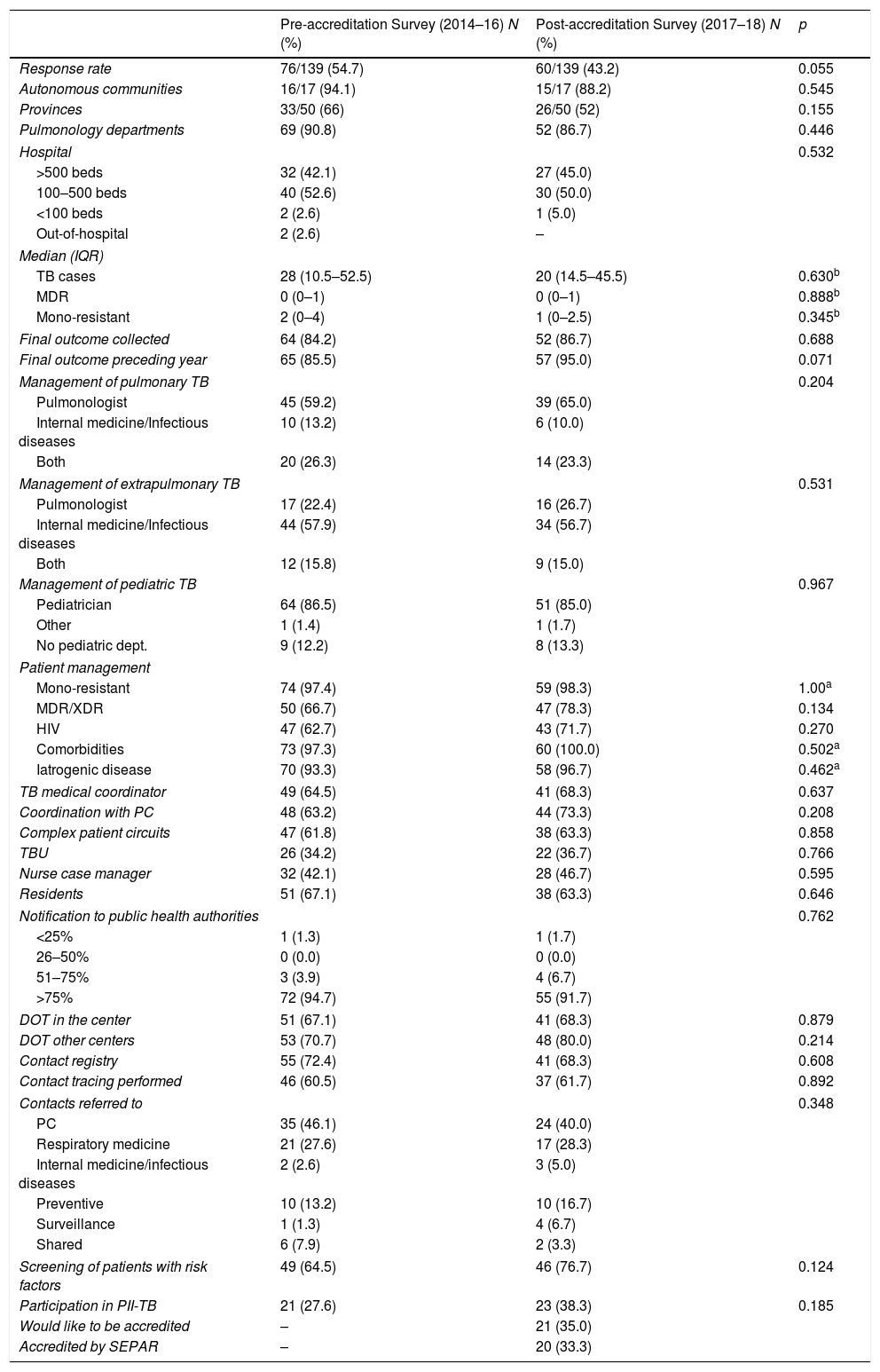

The 76 pre-accreditation questionnaires came from 16/17 (94.1%) autonomous communities and 33/50 (66%) provinces of Spain. A total of 90.8% (69/76) were completed by pulmonology departments or sections, and 7/76 (9.2%) by internal medicine or infectious diseases departments; 42.1% (32) and 52.6% (40) belonged to hospitals with more than 500 and 100–500 beds, respectively. The overall median of TB cases in 2014, 2015 and 2016 was 28 (IQR: 10.5–52.5) per center, and 84.2% (64) recorded the final outcome of treatment. Pulmonary TB was treated by pulmonologists (59.2%) in most sites, while extrapulmonary TB was treated by internal medicine in 57.9% of the hospitals. Contact registries were performed in 72.4% of sites (55), and 60.5% were involved in contact tracing. In 64.5% of sites (49), there was a TB medical coordinator, 63.2% (48) coordinated with PC, and 61.8% (47) coordinated with higher levels of care. A total of 34.2% (26) were already organized as TBUs, 42.1% (32) had a nurse case manager, and 94.7% (72) reported more than 75% of cases to the public health authorities.

In terms of geographical distribution, the 60 pre-accreditation questionnaires came from 15/17 (88.2%) autonomous communities and 26/50 (52%) provinces of Spain. A total of 86.7% (52/60) were completed by pulmonology departments or sections, and 8/60 (13.3%) by internal medicine or infectious diseases departments; 45.0% (27) and 50.0% (30) belonged to hospitals with more than 500 and 100–500 beds, respectively. The median of TB cases in 2017 and 2018 was 20 (IQR: 14.5–45.5) per site, and 86.7% (52) recorded the final outcome of treatment. Contact registries were kept in 68.3% of centers (41) and 61.7% performed contact tracing. In 68.3% of sites (41), there was a TB medical coordinator, 73.3% (44) coordinated with PC, and 63.3% (38) coordinated with higher levels of care. A total of 36.7% (22) were already organized as TBUs, 46.7% (28) had a nurse case manager, and 91.7% (55) reported more than 75% of cases to the public health authorities. Of the 40 non-accredited centers, 21 (52.5%) stated that they would like to be accredited as TBUs.

Table 1 compares the main variables collected from the questionnaire before and after accreditation. No significant changes were found in the different care and coordination settings between the pre- and post-accreditation, although an improvement was noted in the recording of final conclusions.

Comparison of Care and Coordination Variables Collected in the Survey Before and After SEPAR Accreditation of TB Units in Spain (2014–2018).

| Pre-accreditation Survey (2014–16) N (%) | Post-accreditation Survey (2017–18) N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | 76/139 (54.7) | 60/139 (43.2) | 0.055 |

| Autonomous communities | 16/17 (94.1) | 15/17 (88.2) | 0.545 |

| Provinces | 33/50 (66) | 26/50 (52) | 0.155 |

| Pulmonology departments | 69 (90.8) | 52 (86.7) | 0.446 |

| Hospital | 0.532 | ||

| >500 beds | 32 (42.1) | 27 (45.0) | |

| 100–500 beds | 40 (52.6) | 30 (50.0) | |

| <100 beds | 2 (2.6) | 1 (5.0) | |

| Out-of-hospital | 2 (2.6) | – | |

| Median (IQR) | |||

| TB cases | 28 (10.5–52.5) | 20 (14.5–45.5) | 0.630b |

| MDR | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.888b |

| Mono-resistant | 2 (0–4) | 1 (0–2.5) | 0.345b |

| Final outcome collected | 64 (84.2) | 52 (86.7) | 0.688 |

| Final outcome preceding year | 65 (85.5) | 57 (95.0) | 0.071 |

| Management of pulmonary TB | 0.204 | ||

| Pulmonologist | 45 (59.2) | 39 (65.0) | |

| Internal medicine/Infectious diseases | 10 (13.2) | 6 (10.0) | |

| Both | 20 (26.3) | 14 (23.3) | |

| Management of extrapulmonary TB | 0.531 | ||

| Pulmonologist | 17 (22.4) | 16 (26.7) | |

| Internal medicine/Infectious diseases | 44 (57.9) | 34 (56.7) | |

| Both | 12 (15.8) | 9 (15.0) | |

| Management of pediatric TB | 0.967 | ||

| Pediatrician | 64 (86.5) | 51 (85.0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | |

| No pediatric dept. | 9 (12.2) | 8 (13.3) | |

| Patient management | |||

| Mono-resistant | 74 (97.4) | 59 (98.3) | 1.00a |

| MDR/XDR | 50 (66.7) | 47 (78.3) | 0.134 |

| HIV | 47 (62.7) | 43 (71.7) | 0.270 |

| Comorbidities | 73 (97.3) | 60 (100.0) | 0.502a |

| Iatrogenic disease | 70 (93.3) | 58 (96.7) | 0.462a |

| TB medical coordinator | 49 (64.5) | 41 (68.3) | 0.637 |

| Coordination with PC | 48 (63.2) | 44 (73.3) | 0.208 |

| Complex patient circuits | 47 (61.8) | 38 (63.3) | 0.858 |

| TBU | 26 (34.2) | 22 (36.7) | 0.766 |

| Nurse case manager | 32 (42.1) | 28 (46.7) | 0.595 |

| Residents | 51 (67.1) | 38 (63.3) | 0.646 |

| Notification to public health authorities | 0.762 | ||

| <25% | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.7) | |

| 26–50% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75% | 3 (3.9) | 4 (6.7) | |

| >75% | 72 (94.7) | 55 (91.7) | |

| DOT in the center | 51 (67.1) | 41 (68.3) | 0.879 |

| DOT other centers | 53 (70.7) | 48 (80.0) | 0.214 |

| Contact registry | 55 (72.4) | 41 (68.3) | 0.608 |

| Contact tracing performed | 46 (60.5) | 37 (61.7) | 0.892 |

| Contacts referred to | 0.348 | ||

| PC | 35 (46.1) | 24 (40.0) | |

| Respiratory medicine | 21 (27.6) | 17 (28.3) | |

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 2 (2.6) | 3 (5.0) | |

| Preventive | 10 (13.2) | 10 (16.7) | |

| Surveillance | 1 (1.3) | 4 (6.7) | |

| Shared | 6 (7.9) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Screening of patients with risk factors | 49 (64.5) | 46 (76.7) | 0.124 |

| Participation in PII-TB | 21 (27.6) | 23 (38.3) | 0.185 |

| Would like to be accredited | – | 21 (35.0) | |

| Accredited by SEPAR | – | 20 (33.3) | |

DOT: directly observed treatment; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IQR: interquartile range; MDR: multidrug-resistant; PC: Primary care; PII-TB: Integrated Research Program In Tuberculosis; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery; TB: tuberculosis; TBU: tuberculosis unit; XDR: extremely resistant.

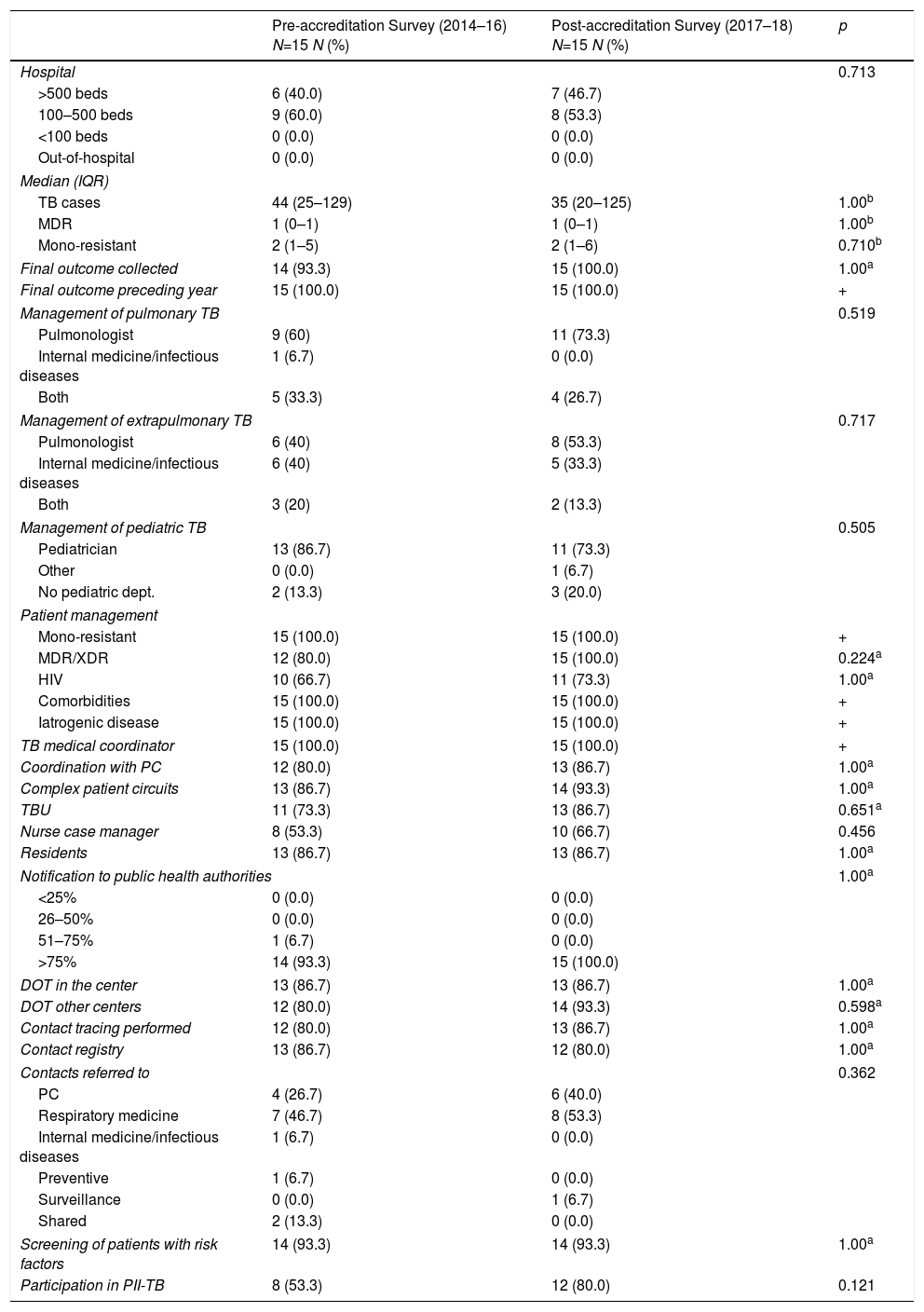

Of all the sites that responded to the survey, 20 were accredited as TBUs, and 15 of these sites completed both questionnaires. When the results of the questionnaire before and after TBU accreditation in these 15 sites were compared, no differences were observed in the organization before and after accreditation (Table 2).

Comparison of Care and Coordination Variables Collected in the Survey Before and After SEPAR Accreditation Among SEPAR-accredited TBUs (2014–2018).

| Pre-accreditation Survey (2014–16) N=15 N (%) | Post-accreditation Survey (2017–18) N=15 N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | 0.713 | ||

| >500 beds | 6 (40.0) | 7 (46.7) | |

| 100–500 beds | 9 (60.0) | 8 (53.3) | |

| <100 beds | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Out-of-hospital | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Median (IQR) | |||

| TB cases | 44 (25–129) | 35 (20–125) | 1.00b |

| MDR | 1 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 1.00b |

| Mono-resistant | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) | 0.710b |

| Final outcome collected | 14 (93.3) | 15 (100.0) | 1.00a |

| Final outcome preceding year | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | + |

| Management of pulmonary TB | 0.519 | ||

| Pulmonologist | 9 (60) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Both | 5 (33.3) | 4 (26.7) | |

| Management of extrapulmonary TB | 0.717 | ||

| Pulmonologist | 6 (40) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 6 (40) | 5 (33.3) | |

| Both | 3 (20) | 2 (13.3) | |

| Management of pediatric TB | 0.505 | ||

| Pediatrician | 13 (86.7) | 11 (73.3) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) | |

| No pediatric dept. | 2 (13.3) | 3 (20.0) | |

| Patient management | |||

| Mono-resistant | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | + |

| MDR/XDR | 12 (80.0) | 15 (100.0) | 0.224a |

| HIV | 10 (66.7) | 11 (73.3) | 1.00a |

| Comorbidities | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | + |

| Iatrogenic disease | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | + |

| TB medical coordinator | 15 (100.0) | 15 (100.0) | + |

| Coordination with PC | 12 (80.0) | 13 (86.7) | 1.00a |

| Complex patient circuits | 13 (86.7) | 14 (93.3) | 1.00a |

| TBU | 11 (73.3) | 13 (86.7) | 0.651a |

| Nurse case manager | 8 (53.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0.456 |

| Residents | 13 (86.7) | 13 (86.7) | 1.00a |

| Notification to public health authorities | 1.00a | ||

| <25% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 26–50% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 51–75% | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| >75% | 14 (93.3) | 15 (100.0) | |

| DOT in the center | 13 (86.7) | 13 (86.7) | 1.00a |

| DOT other centers | 12 (80.0) | 14 (93.3) | 0.598a |

| Contact tracing performed | 12 (80.0) | 13 (86.7) | 1.00a |

| Contact registry | 13 (86.7) | 12 (80.0) | 1.00a |

| Contacts referred to | 0.362 | ||

| PC | 4 (26.7) | 6 (40.0) | |

| Respiratory medicine | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | |

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Preventive | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Surveillance | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.7) | |

| Shared | 2 (13.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Screening of patients with risk factors | 14 (93.3) | 14 (93.3) | 1.00a |

| Participation in PII-TB | 8 (53.3) | 12 (80.0) | 0.121 |

+: constant.

DOT: directly observed treatment; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IQR: interquartile range; MDR: multidrug-resistant; PC: Primary care; PII-TB: Integrated Research Program In Tuberculosis; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery; TB: tuberculosis; TBU: tuberculosis unit; XDR: extremely resistant.

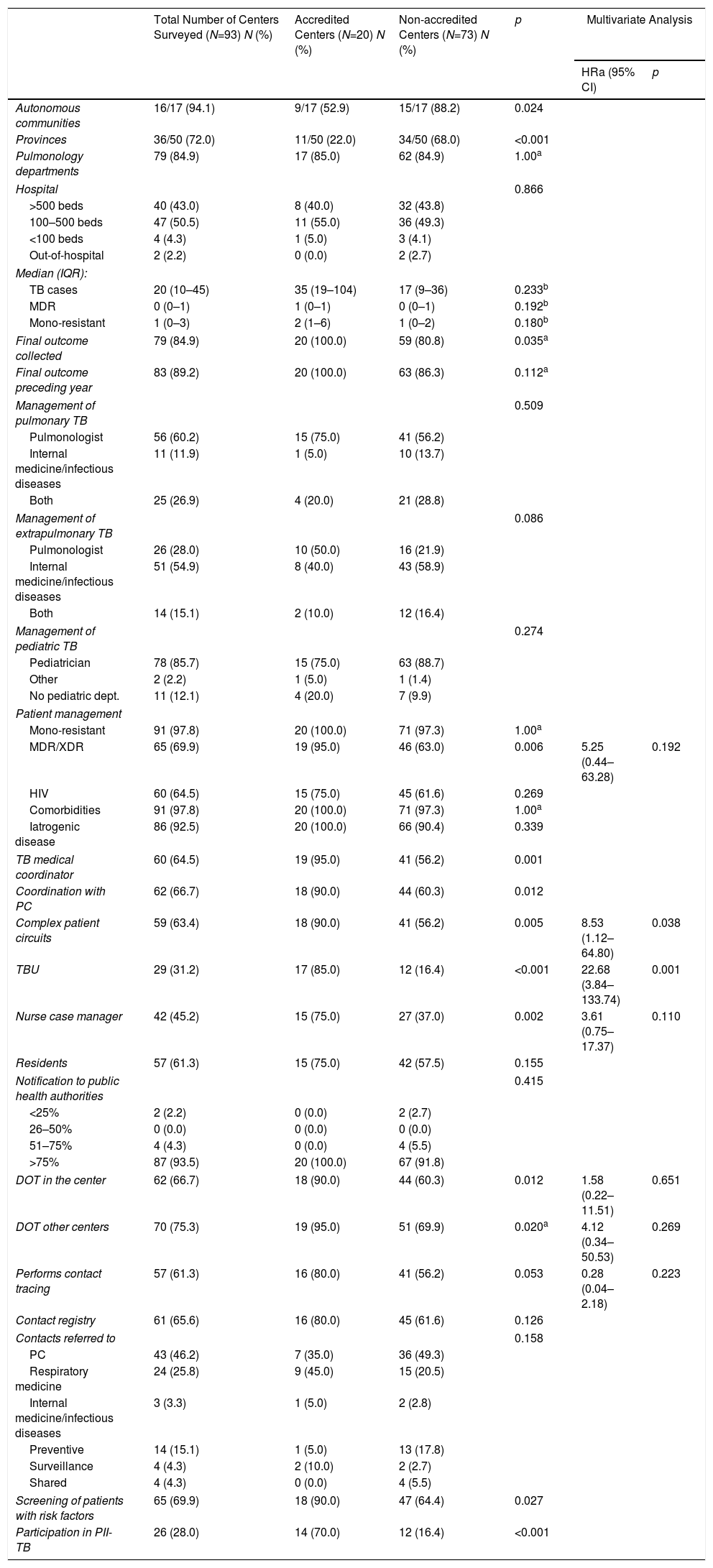

The comparison of the 20 accredited sites with the 73 non-accredited sites show statistically significant differences. A higher percentage of the accredited sites record the final outcome of cases, coordinate with PC, have a TB medical coordinator, and use referral circuits to send patients to other more complex departments. A greater proportion of these sites also manage patients with multiresistant or extremely resistant TB, have the capacity to facilitate DOT on-site or in other centers, perform contact tracing, and have a TB nurse case manager. Accredited sites are located in only 9 autonomous communities and most of these sites already had a TBU, and participated by contributing cases to the PII-TB registry (Table 3).

Comparison of Care and Coordination Variables Collected in the Survey Before and After SEPAR Accreditation Among SEPAR-accredited and Non-accredited TBUs (2014–2018).

| Total Number of Centers Surveyed (N=93) N (%) | Accredited Centers (N=20) N (%) | Non-accredited Centers (N=73) N (%) | p | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRa (95% CI) | p | |||||

| Autonomous communities | 16/17 (94.1) | 9/17 (52.9) | 15/17 (88.2) | 0.024 | ||

| Provinces | 36/50 (72.0) | 11/50 (22.0) | 34/50 (68.0) | <0.001 | ||

| Pulmonology departments | 79 (84.9) | 17 (85.0) | 62 (84.9) | 1.00a | ||

| Hospital | 0.866 | |||||

| >500 beds | 40 (43.0) | 8 (40.0) | 32 (43.8) | |||

| 100–500 beds | 47 (50.5) | 11 (55.0) | 36 (49.3) | |||

| <100 beds | 4 (4.3) | 1 (5.0) | 3 (4.1) | |||

| Out-of-hospital | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | |||

| Median (IQR): | ||||||

| TB cases | 20 (10–45) | 35 (19–104) | 17 (9–36) | 0.233b | ||

| MDR | 0 (0–1) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.192b | ||

| Mono-resistant | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–6) | 1 (0–2) | 0.180b | ||

| Final outcome collected | 79 (84.9) | 20 (100.0) | 59 (80.8) | 0.035a | ||

| Final outcome preceding year | 83 (89.2) | 20 (100.0) | 63 (86.3) | 0.112a | ||

| Management of pulmonary TB | 0.509 | |||||

| Pulmonologist | 56 (60.2) | 15 (75.0) | 41 (56.2) | |||

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 11 (11.9) | 1 (5.0) | 10 (13.7) | |||

| Both | 25 (26.9) | 4 (20.0) | 21 (28.8) | |||

| Management of extrapulmonary TB | 0.086 | |||||

| Pulmonologist | 26 (28.0) | 10 (50.0) | 16 (21.9) | |||

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 51 (54.9) | 8 (40.0) | 43 (58.9) | |||

| Both | 14 (15.1) | 2 (10.0) | 12 (16.4) | |||

| Management of pediatric TB | 0.274 | |||||

| Pediatrician | 78 (85.7) | 15 (75.0) | 63 (88.7) | |||

| Other | 2 (2.2) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (1.4) | |||

| No pediatric dept. | 11 (12.1) | 4 (20.0) | 7 (9.9) | |||

| Patient management | ||||||

| Mono-resistant | 91 (97.8) | 20 (100.0) | 71 (97.3) | 1.00a | ||

| MDR/XDR | 65 (69.9) | 19 (95.0) | 46 (63.0) | 0.006 | 5.25 (0.44–63.28) | 0.192 |

| HIV | 60 (64.5) | 15 (75.0) | 45 (61.6) | 0.269 | ||

| Comorbidities | 91 (97.8) | 20 (100.0) | 71 (97.3) | 1.00a | ||

| Iatrogenic disease | 86 (92.5) | 20 (100.0) | 66 (90.4) | 0.339 | ||

| TB medical coordinator | 60 (64.5) | 19 (95.0) | 41 (56.2) | 0.001 | ||

| Coordination with PC | 62 (66.7) | 18 (90.0) | 44 (60.3) | 0.012 | ||

| Complex patient circuits | 59 (63.4) | 18 (90.0) | 41 (56.2) | 0.005 | 8.53 (1.12–64.80) | 0.038 |

| TBU | 29 (31.2) | 17 (85.0) | 12 (16.4) | <0.001 | 22.68 (3.84–133.74) | 0.001 |

| Nurse case manager | 42 (45.2) | 15 (75.0) | 27 (37.0) | 0.002 | 3.61 (0.75–17.37) | 0.110 |

| Residents | 57 (61.3) | 15 (75.0) | 42 (57.5) | 0.155 | ||

| Notification to public health authorities | 0.415 | |||||

| <25% | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.7) | |||

| 26–50% | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |||

| 51–75% | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | |||

| >75% | 87 (93.5) | 20 (100.0) | 67 (91.8) | |||

| DOT in the center | 62 (66.7) | 18 (90.0) | 44 (60.3) | 0.012 | 1.58 (0.22–11.51) | 0.651 |

| DOT other centers | 70 (75.3) | 19 (95.0) | 51 (69.9) | 0.020a | 4.12 (0.34–50.53) | 0.269 |

| Performs contact tracing | 57 (61.3) | 16 (80.0) | 41 (56.2) | 0.053 | 0.28 (0.04–2.18) | 0.223 |

| Contact registry | 61 (65.6) | 16 (80.0) | 45 (61.6) | 0.126 | ||

| Contacts referred to | 0.158 | |||||

| PC | 43 (46.2) | 7 (35.0) | 36 (49.3) | |||

| Respiratory medicine | 24 (25.8) | 9 (45.0) | 15 (20.5) | |||

| Internal medicine/infectious diseases | 3 (3.3) | 1 (5.0) | 2 (2.8) | |||

| Preventive | 14 (15.1) | 1 (5.0) | 13 (17.8) | |||

| Surveillance | 4 (4.3) | 2 (10.0) | 2 (2.7) | |||

| Shared | 4 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (5.5) | |||

| Screening of patients with risk factors | 65 (69.9) | 18 (90.0) | 47 (64.4) | 0.027 | ||

| Participation in PII-TB | 26 (28.0) | 14 (70.0) | 12 (16.4) | <0.001 | ||

DOT: directly observed treatment; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IQR: interquartile range; MDR: multidrug-resistant; ORa: adjusted odds ratio; PII-TB: Integrated Research Program In Tuberculosis; PC: primary care; PH: public health authorities; SEPAR: Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery; TB: tuberculosis; TBEP: extrapulmonary tuberculosis; TBU: tuberculosis unit; XDR: extremely resistant.

When the 20 accredited sites were compared with the 73 unaccredited sites, the logistic regression model indicates that the variables associated with TBU accreditation were constituting a TBU (ORa=22.68; 95% CI: 3.84–133.74; p=0.001) and availability of referral circuits to other more complex departments (ORa=8.53; 95% CI: 1.12–64.80; p=0.038) (Table 3).

DiscussionThis study has helped us understand how TB is managed in pulmonology departments and sections and by other professionals involved in the treatment of this disease in Spain. It has also helped characterize the differences between accredited and non-accredited sites. According to survey respondents, pulmonary TB is managed, above all, by pulmonologists, and extrapulmonary TB is managed by internists. In a high proportion of sites, cases are followed up until treatment completion, resistance and comorbidities are managed, and DOT is offered to patients. However, contact registries and tracing should be improved in pulmonology and preventive medicine departments, and, while the percentage of cases reported to the public health authorities is high, sites were identified in which reporting is less than 75%, despite TB being a notifiable disease.

The results obtained from self-administered questionnaires reveal no significant differences between the different care and coordination variables among sites that completed the pre- and post-accreditation questionnaire. Moreover, accredited sites that completed both questionnaires (N=15) also showed no organizational differences before and after accreditation. Finally, when the accredited sites were compared with the non-accredited sites, statistically significant differences were observed in organizational and patient care variables. The multivariate analysis indicates that constituting a TBU and having referral circuits to other more complex departments are associated with accreditation as a TBU.

The lack of significant improvements observed in SEPAR accredited sites before and after accreditation could be attributed to the fact that those sites were already managing TB effectively and correctly before applying for accreditation. Moreover, our sample size is small and has low statistical power. However, differences were found between accredited and non-accredited sites, and this could be due to the fact that accredited sites already have better organization and better indicators. Accreditation involves reviewing and implementing actions to improve disease management and control, and evaluating and reorganizing staff and their activities.

As study limitations, we must mention that it was impossible to verify the responses, and that the post-accreditation questionnaires were administered only 2 years after initiating the accreditation process. More time may be needed to increase the number of accredited TBUs and assess their progress. In any case, accreditation of TBUs could encourage other units to seek accreditation. The management and treatment of immunocompromised patients (biological treatments, elderly individuals, etc.) in TBUs could be evaluated in greater depth in the questionnaires, since this is a particularly vulnerable population.

There is evidence that in large cities in countries with a low incidence of TB, the efficiency of control programs can be increased with organizational improvements.1,4 With regard to outcomes, other authors have also associated better TB control with improved organization based on the creation of TBUs. More specifically, a study conducted to assess the impact of setting up a TBU in Barcelona concluded that this intervention improved contact tracing.3 This is similar to the findings of our study when accredited sites were compared with non-accredited sites. Comparable results were observed in the Galician TB Program, organized around 7 TBUs.12 The key points for organizing TB management highlighted by all these studies were the centralization of TB care, the role of nurse case managers, and coordination and communication between the different areas and professionals involved.1,3 Accredited units presented better indicators than non-accredited units in all of these areas.

The Autonomous Community of Madrid carried out an evaluation of TB control and found high rates of cases lost to follow-up and a low rate of contact tracing. The authors underlined the need to centralize the follow-up of patients and contact tracing in the TBU to improve outcomes.13 Other publications recommend that, because the low incidence prevents PCPs from accumulating experience, TB care must be centralized, with constant communication between coordinated groups of specialized professionals.5,14–16

A study conducted in the United Kingdom concluded that good disease control depends on the availability of an appropriate number of TB specialists. One TB control strategy was the availability of 1 dedicated TB nurse for every 40 patients.2 Our study does not permit adequate comparisons, but the percentage of sites with TB nurse case managers and TB medical coordinators was much higher among accredited units.

Along the same lines, the consensus on TB control in large cities produced by a working group representing several large cities in the European Union stresses the importance of organizing the center to ensure patient access, incorporating sufficient experienced personnel, and promoting strong collaboration and coordination between sectors.4

A systematic review on interventions that improve adherence and TB treatment outcomes concluded that the administration of DOT and patient education increase therapeutic adherence and success rates.17

It is important to note that, although TB is a notifiable disease, underreporting of cases to the public health authorities has been observed in some sites in Spain, thus complicating disease control. A study by Gimenez-Duran et al. revealed underreporting in the Balearic Islands from anti-tuberculosis drug prescriptions,18 and another by Morales-Garcia et al. observed significant underreporting in 16 Spanish hospitals, and stressed that sites that had a nurse case manager had reporting rates of 100%,19 reinforing the importance of this figure in the TBU.

According to a study conducted in California, implementing systematic annual assessment and indicator-based improvement processes in TB control programs improved outcomes.20 This would support the adoption of indicators as tools for improving outcomes in accredited sites. A questionnaire administered to 31 countries in the EU and European Economic Area to determine TB control strategies identified a number of priority actions: reaching vulnerable population groups, actively detecting TB in high-risk groups, implementating electronic records and contact tracing, controlling multidrug-resistant TB, and centralizing care.21

All of the above-mentioned studies support the use of organizational indicators, such as appointing a nurse case manager, performing contact tracing, administering appropriate treatment, administering DOT, and coordinating with other departments and professionals.22,23 TB unit accreditation is a SEPAR initiative that gives a quality seal of approval to units that meet a series of objective criteria based on indicators used in previous studies.6 Moreover, the creation of a TBU can help achieve the goals of the World Health Organization End TB strategy.24

Although several positive aspects have been detected, such as recording final outcomes, notifying public health authorities, managing resistance, and controlling associated or iatrogenic diseases, there were also several areas for improvement. The latter include appointing a TB medical coordinator, organizing contact registries and tracing, creating referral and coordination circuits, and appointing nurse case managers. This last recommendation is paramount for the management of TB, and is one of the most important improvements noted in accredited TBUs. The significant differences in results and operation between accredited and non-accredited units should compel the latter units to improve their organization and try to meet the criteria required for accreditation.

ConclusionsThis study sheds light on the current organization of TB management and control in Spain and on the impact of SEPAR TBU accreditation.

TBUs must be closely supervised using simple annual indicators that can even be used to facilitate self-assessment. The progressive improvement of the effectiveness of the TBUs, along with an equally progressive increase in accreditations, whether for new applications or in response to an increase in the level of complexity and re-accreditations, would contribute to the improvement of the organization of TB control in Spain.

FundingThis study was funded by a grant from the Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR 114/2013) (PI: Joan Pau Millet), Spain.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

We thank all the clinicians who participated in the study by responding to the surveys.

| Questionnaire fields |

|---|

| Date of completion |

| Completed by: Full name |

| Specialty |

| Department |

| Workplace details |

| Type of site (Hospital<100 beds/Hospital 100–500 beds/Hospital>500 beds/Out-of-Hospital) |

| City where workplace is located |

| Province where workplace is located |

| Area of influence |

| Total population |

| Number of tuberculosis cases treated: |

| Who treats pulmonary and pleural tuberculosis in your center? |

| Number of cases of MDR-TB: |

| Number of mono-resistant cases: |

| Are the final outcomes of the patients recorded? |

| Could you know what happened with patients in 2016? |

| Who treats extrapulmonary (not pleural) tuberculosis in your center? |

| Who treats pediatric tuberculosis in your center? |

| Do you have clearly defined coordination circuits with Primary Care? |

| Is there a TB medical coordinator in your center? |

| Do you have the capacity to manage mono-resistant patients? |

| Do you have clearly defined circuits of referral to other healthcare departments that can treat highly complex patients? |

| Is your unit already a specific TB unit? |

| Can you provide medication and give DOT in your center? |

| Contact tracing: Do you keep a contact registry? |

| Contact tracing: Are contacts studied directly? |

| Contact tracing: If they are referred, where are they referred to? |

| What is the percentage of cases where at least 1 contact is traced? |

| Do you perform screening and follow-up of patients with risk factors (indigents, IVDU, HIV, biological treatments, etc.)? |

| Do you have a nurse case manager? |

| Do you have residents in training? |

| What estimated percentage of cases are reported to the public health authorities? |

| Were you involved in contributing cases to the SEPAR PII-TB database in 2014? |

| Have you been accredited as a Tuberculosis Unit by SEPAR? |

| Have you any comments on the data provided? |

| Do you have the capacity to manage MDR/XDR patients? |

| Do you have the capacity to manage HIV patients? |

| Do you have the capacity to manage patients with comorbidities? |

| Do you have the capacity to manage patients with iatrogenic diseases? |

| Can you provide medication and give DOT in other sites? |

| Do you have a case manager nurse for patients and contacts? |

| Do you have a contact manager nurse? |

| If you are not yet accredited, would you like to be accredited as a Tuberculosis Unit by SEPAR? |

Please cite this article as: Brugueras S, Roldán L, Rodrigo T, García-García J-M, Caylà JA, García-Pérez FJ, et al. Organización del control de la tuberculosis en España: evaluación de una estrategia dirigida a fomentar la acreditación de unidades de tuberculosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:90–98.