The diagnostic and therapeutic utility of bronchoscopy, along with its minimal morbidity and mortality, have made it an increasingly useful technique in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). It permits direct dynamic inspection of the airway and facilitates the diagnosis and management of a wide variety of both supra- and infraglottic disorders.

We performed a retrospective descriptive study of 32 bronchoscopies performed in 23 NICU patients in a tertiary hospital over a 5-year period (2014–2018). We recorded patient characteristics, type of bronchoscope, anesthesia, reason for the examination, findings, and complications. A Pentax flexible 2.8mm bronchoscope was used in all cases.

The average gestational age of the patients was 36weeks (IQR 33–38) (50 % preterm infants), with a median weight of 2345g (1,900-2,800), 11 boys and 12 girls. Underlying diseases included 6 cases of esophageal atresia.

The procedure was performed by a pediatric pulmonologist in infants with an average age of 32 days (8–65) and an average weight of 2900g (2,570-3,290) admitted to the neonatal unit. Patient care was the responsibility of the neonatologist. All procedures were performed under sedation, primarily ketamine. Respiratory support was used during the procedure, as follows: high flow nasal prongs in 9 (28.1 %), mechanical ventilation in 9 (28.1 %), CPAP in 5 (15.6 %), standard nasal prongs in 2 (6.3 %), laryngeal mask in 1 (3.1 %), and no support in 6 (18.8 %).

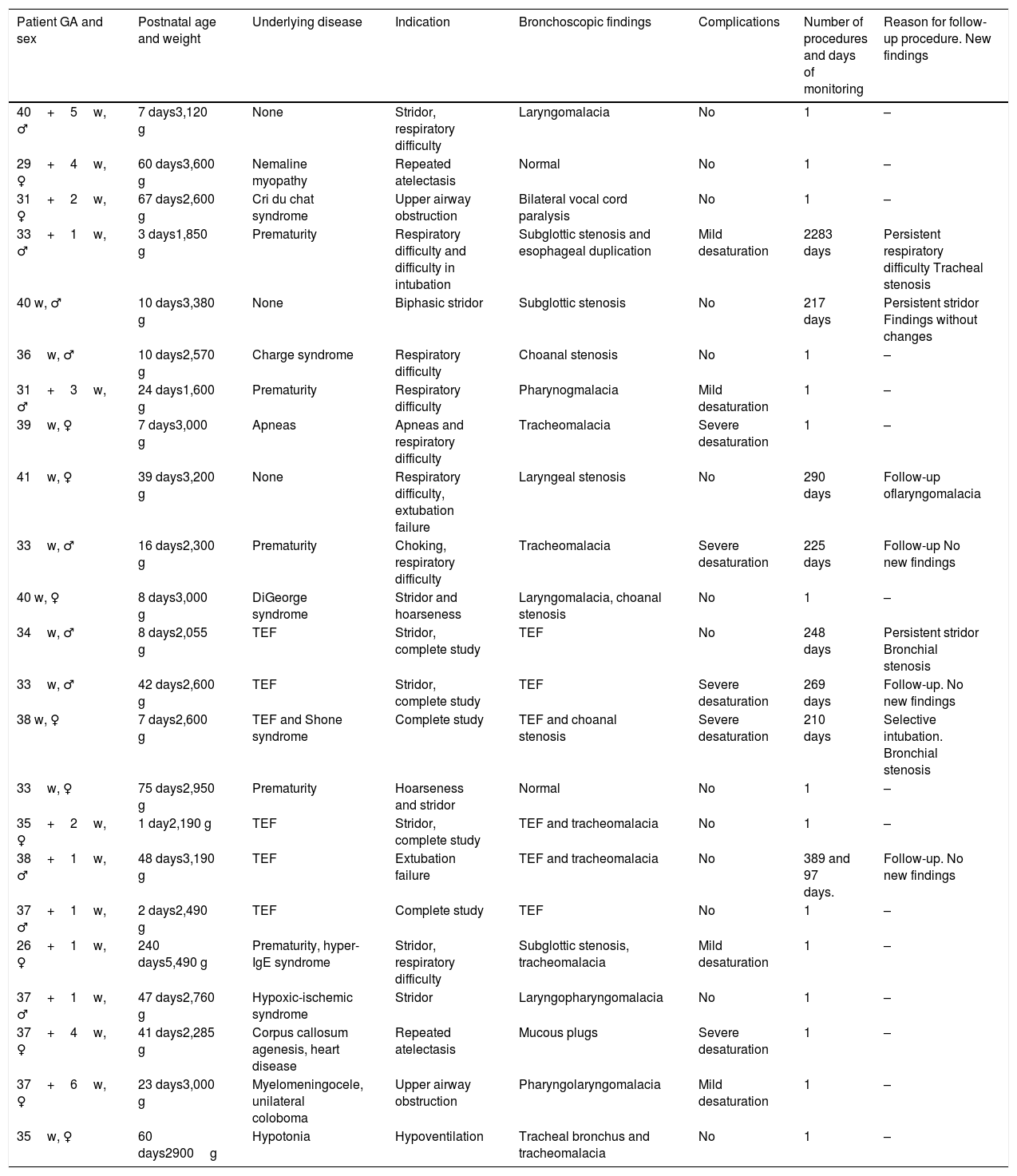

The indications (Table 1) that led to the realization of the procedure were: tracheoesophageal fistula (8), stridor (7), respiratory difficulty (3), difficulty to intubate (4), failure to extubate (3), atelectasis (2), upper airway obstruction (2), hypoventilation (1), and selective intubation (1).

Patient characteristics.

| Patient GA and sex | Postnatal age and weight | Underlying disease | Indication | Bronchoscopic findings | Complications | Number of procedures and days of monitoring | Reason for follow-up procedure. New findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40+5w, ♂ | 7 days3,120 g | None | Stridor, respiratory difficulty | Laryngomalacia | No | 1 | – |

| 29+4w, ♀ | 60 days3,600 g | Nemaline myopathy | Repeated atelectasis | Normal | No | 1 | – |

| 31+2w, ♀ | 67 days2,600 g | Cri du chat syndrome | Upper airway obstruction | Bilateral vocal cord paralysis | No | 1 | – |

| 33+1w, ♂ | 3 days1,850 g | Prematurity | Respiratory difficulty and difficulty in intubation | Subglottic stenosis and esophageal duplication | Mild desaturation | 2283 days | Persistent respiratory difficulty Tracheal stenosis |

| 40 w, ♂ | 10 days3,380 g | None | Biphasic stridor | Subglottic stenosis | No | 217 days | Persistent stridor Findings without changes |

| 36w, ♂ | 10 days2,570 g | Charge syndrome | Respiratory difficulty | Choanal stenosis | No | 1 | – |

| 31+3w, ♂ | 24 days1,600 g | Prematurity | Respiratory difficulty | Pharynogmalacia | Mild desaturation | 1 | – |

| 39w, ♀ | 7 days3,000 g | Apneas | Apneas and respiratory difficulty | Tracheomalacia | Severe desaturation | 1 | – |

| 41w, ♀ | 39 days3,200 g | None | Respiratory difficulty, extubation failure | Laryngeal stenosis | No | 290 days | Follow-up oflaryngomalacia |

| 33w, ♂ | 16 days2,300 g | Prematurity | Choking, respiratory difficulty | Tracheomalacia | Severe desaturation | 225 days | Follow-up No new findings |

| 40 w, ♀ | 8 days3,000 g | DiGeorge syndrome | Stridor and hoarseness | Laryngomalacia, choanal stenosis | No | 1 | – |

| 34w, ♂ | 8 days2,055 g | TEF | Stridor, complete study | TEF | No | 248 days | Persistent stridor Bronchial stenosis |

| 33w, ♂ | 42 days2,600 g | TEF | Stridor, complete study | TEF | Severe desaturation | 269 days | Follow-up. No new findings |

| 38 w, ♀ | 7 days2,600 g | TEF and Shone syndrome | Complete study | TEF and choanal stenosis | Severe desaturation | 210 days | Selective intubation. Bronchial stenosis |

| 33w, ♀ | 75 days2,950 g | Prematurity | Hoarseness and stridor | Normal | No | 1 | – |

| 35+2w, ♀ | 1 day2,190 g | TEF | Stridor, complete study | TEF and tracheomalacia | No | 1 | – |

| 38+1w, ♂ | 48 days3,190 g | TEF | Extubation failure | TEF and tracheomalacia | No | 389 and 97 days. | Follow-up. No new findings |

| 37+1w, ♂ | 2 days2,490 g | TEF | Complete study | TEF | No | 1 | – |

| 26+1w, ♀ | 240 days5,490 g | Prematurity, hyper-IgE syndrome | Stridor, respiratory difficulty | Subglottic stenosis, tracheomalacia | Mild desaturation | 1 | – |

| 37+1w, ♂ | 47 days2,760 g | Hypoxic-ischemic syndrome | Stridor | Laryngopharyngomalacia | No | 1 | – |

| 37+4w, ♀ | 41 days2,285 g | Corpus callosum agenesis, heart disease | Repeated atelectasis | Mucous plugs | Severe desaturation | 1 | – |

| 37+6w, ♀ | 23 days3,000 g | Myelomeningocele, unilateral coloboma | Upper airway obstruction | Pharyngolaryngomalacia | Mild desaturation | 1 | – |

| 35w, ♀ | 60 days2900g | Hypotonia | Hypoventilation | Tracheal bronchus and tracheomalacia | No | 1 | – |

GA: gestational age; TEF: tracheoesophageal fistula.

Of the total bronchoscopies, 23/32 (69 %) were diagnostic; of these, 21/23 (91 %) revealed pathology and more than one abnormality was found during the examination in 10/23 (43 %). Nine bronchoscopies (9/32) were performed to monitor progress. In 4 of these, no new findings were revealed. It is interesting to note that in 1 of the control bronchoscopies, selective intubation could be performed in a patient with recurrent pneumothorax.

The most frequent bronchoscopic diagnoses were malacia and stenosis at different levels. Findings are summarized in Table 1.

During the procedure, 5 patients had transient hypoxemia that required the temporary withdrawal of the bronchoscope, although the examination of the airway could be completed in all patients. There were no significant differences in complications between preterm and term infants.

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is a technique increasingly used in the NICU for its high diagnostic yield and safety record.1

Patients admitted to these units often have episodes of respiratory difficulty, repeated atelectasis, or intubation or extubation problems.1,2 In all these processes, bronchoscopy may be required, or at least advisable.3 Moreover, direct visualization of the airway is essential for the diagnosis of possible malformations. This technique is usually performed under sedation, permitting dynamic airway examination. The indications for the procedure tend to be: stridor, atelectasis, respiratory distress, or difficulty in intubation.4 The most common bronchoscopic findings are mucous plugs, stenosis, and malacia at different levels.1,5

A high percentage of procedures reveal multiple diagnoses, so a full exploration of the upper and lower airway in each procedure is essential. In the case of suspected pneumonia or unilateral lung disease, bronchoalveolar lavage can also be performed during the procedure,6 which can be useful both for designing antibiotic regimens and for diagnosing certain uncommon but not unknown diseases, such as altered surfactant synthesis.

The most common complications are bradycardias and mild hypoxia.1 However, some authors believe that these situations are inherent to the procedure itself and cannot be considered complications,7 since the vast majority are transitory and resolve after temporary withdrawal of the bronchoscope. The procedure is usually conducted in neonatal units with continuous monitoring and under the supervision of the neonatologist.

We can, then, conclude that bronchoscopy is a very useful technique in the NICU and one that offers a high safety profile in expert hands.

Please cite this article as: Castillo MdCL, Ruiz EP, Aguilera PC, García ES, Frías JP. Broncoscopias en unidades de cuidados intensivos neonatales. Arch Bronconeumol. 2020;56:120–121.