The most common causes of pleural effusion in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) are infections (bacterial or viral), other malignancy, chemotherapy and those derived from the malignant process itself. Survival is determined by response to treatment of the hematological disease.1

A minimum sample volume of 60mL is required for the cytomorphological diagnosis of malignancy in pleural fluid.2

In cases of pleural effusion refractory to treatment of the underlying disease, pleurodesis must be performed to control respiratory symptoms.

This letter reports the case of a 76-year-old patient with AML diagnosed 2 months previously with compatible bone marrow phenotype and normal cytogenetic results (46,XY[15]) who had received 3 cycles of 5-azacitidine.

He was admitted for dyspnea, 38°C fever and tachycardia (120bpm). He had leukocytosis (45×109/L), anemia (hemoglobin 88g/L), thrombocytosis (719×109/L) and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 1.663IU/L (normal: 125–220IU/L). Chest X-ray and computed tomography showed significant left pleural effusion.

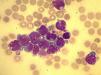

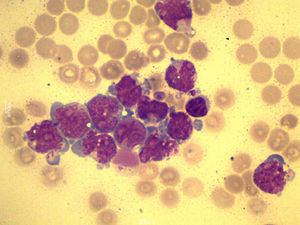

A total of 90mL of pleural fluid were obtained by thoracocentesis. This contained 1200 lymphocytes/μL (normal: <200/μL), glucose 52mg/dL (normal: 70–110mg/dL), LDH 1724IU/L (normal: 125–220IU/L) and pH was 7.38. Microbiological cultures were negative. Cytocentrifugation and May-Grünwald/Giemsa staining of the pleural fluid were performed for microscopic examination (Fig. 1). The presence of myeloblasts in pleural fluid was confirmed by flow cytometry immunophenotyping (CD34, CD33, CD13 and CD117, but not CD14 or CD15). Cytogenetic examination with G-banding was normal, consistent with the patient's AML phenotype.

A diagnosis of leukemic pleural effusion was established and pleural drainage was performed, with little response. One week later, the patient required pleurodesis with bleomycin to control dyspnea derived from worsening pleural effusion. His respiratory syndrome worsened progressively until exitus at 15 days.

In the case of leukemic pleural effusion, the clonal cell line must be confirmed with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).3

In the routine screening of these patients for the indication of pleurodesis, there is no clear correlation between pleural fluid pH and survival; clinical status appears to be the best predictor for post-pleurodesis survival.

In patients who have not previously undergone pleurodesis, no significant differences in dyspnea relief have been found between permanent pleural catheter drainage and talc pleurodesis.4

Both bleomycin and talc have been shown to be good sclerosing agents, with similar efficacy in pleurodesis for the control of symptomatic malignant pleural effusion. Although bleomycin was used in our patient, it is important to note that talc is cheaper and may have the same or better success rate in the reduction of recurrent malignant pleural effusion than bleomycin and other sclerosing agents, although this difference has not been shown to be statistically significant.5

The use of many sclerosing agents in pleurodesis has been reported, including iodized povidone, doxycycline, silver nitrate, interferon alpha-2b and others. Good results have been documented, but disparity in the design of these studies make comparison difficult. Future studies are required to reach a consensus on the best method of pleurodesis in these patients.

Please cite this article as: Morell-García D, Bauça JM, López Andrade B. Derrame pleural leucémico: aproximación diagnóstica y controversias en pleurodesis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2014;50:371–372.