Smoking around the world has been decreasing. In 2000, 33% of adults were smokers, a figure that fell to 23.5% in 2018. Whenever there has been concern about the health effects of tobacco, the industry has tried to get around it by offering dubious relief such as the cellulose filter in the 1950s or light and low-tar combustible cigarettes (CC) in the 1970s and later. Since 2007, they have promoted electronic cigarettes, known generically as Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS). These products were born on the fringes of pre-existing tobacco regulations, allowing the consumption of these new products to increase dramatically.1

These were followed by the relaunch of devices, which manufacturers claims do not burn tobacco, being known as “Heat not Burn tobacco products” (HNB). The HNBs. The first was introduced in1988, as Premier™, followed by Eclipse™ from RJ Reynolds Tobacco Company (RJR) and Accord™ from Phillip Morris International (PMI). Several devices are currently marketed, the most widespread being the IQOS™ (PMI), acronym for I Quit Ordinary Smoking,2,3 by 2022, PMI was promoting it in nearly 60 countries.4

IQOS™ was first sold in Japan in December 2013,5 which quickly became a best-seller after being advertised on a popular Japanese television show.6 Three years later, in Italy, 329,000 people who had not previously been smokers, used HNB,7 demonstrating that heated tobacco can initiate and maintain an addictive process to nicotine. By 2020, United States authorized IQOS™ to use reduced exposure messages in its marketing, but due to a lack of evidence, it did not authorize the use of reduced risk or harm messages.8

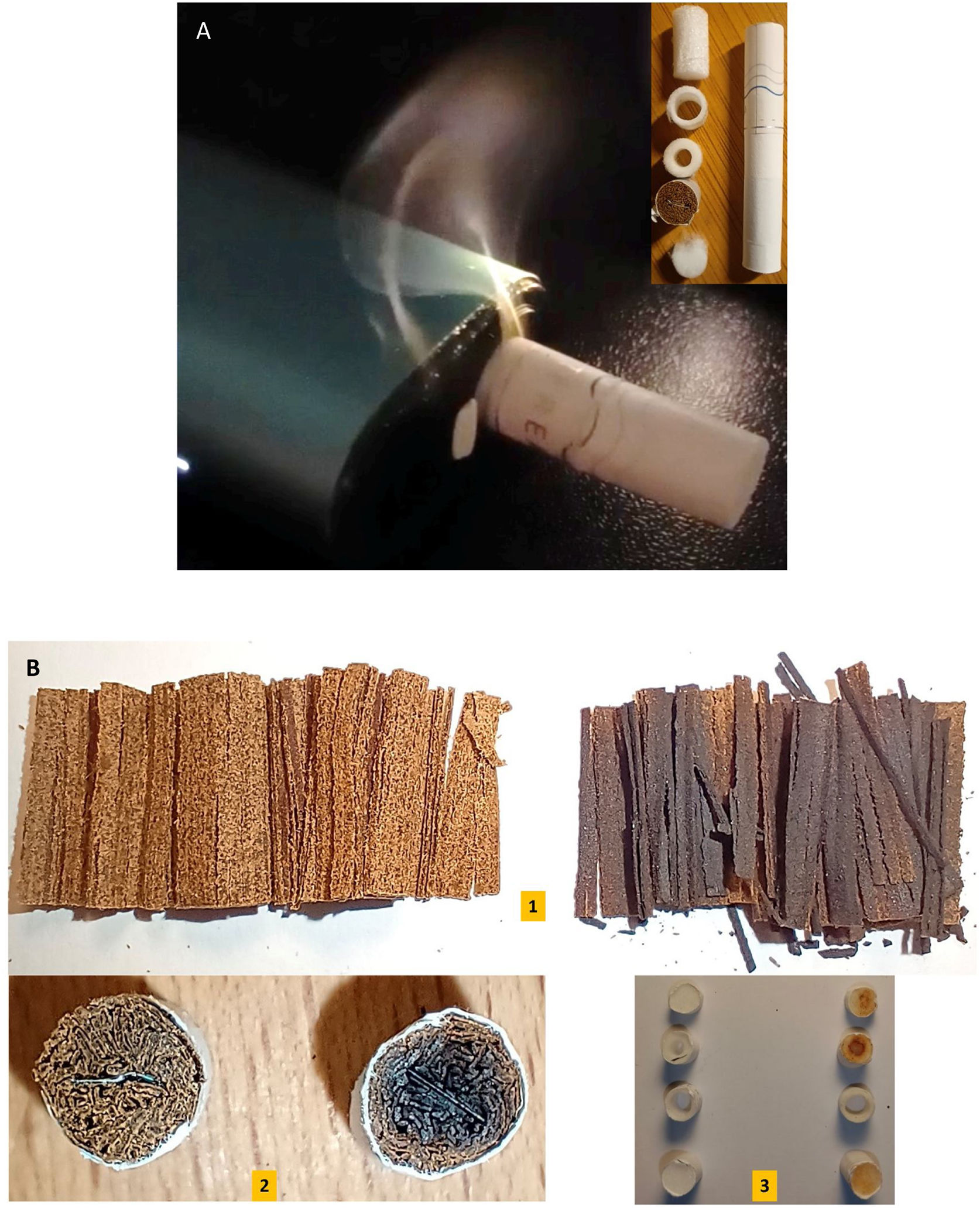

PMI has recently presented an updated version, the IQOS ILUMA™. It uses induction, a very old and well-known physical principle, to warm a modified cigarette (Fig. 1A). This device has an electronic control circuit, a rechargeable battery and a coil that generates an electromagnetic field which heats a metal foil previously inserted inside a tobacco plug (Fig. 1B-2). The manufacturer assures that it does not burn tobacco but, at the same time, recognizes the emission of some degree of carbon monoxide (CO) (https://es.iqos.com/es).

(A) Smoke delivered by unit, and exploded view of a specific cigarette for induction use. (B) Changes in tobacco and filters. For all images: on the left before, on the right after smoking. Note the charring of the tobacco, (1) Tobacco extracted from the specific cigarette of the device. (2) Device-specific cigarette modified tobacco plug (note the inductive metal located in direct contact with the tobacco). (3) Filters normally in the body of the cigarette.

Our aim is to determine whether combustion occurs and hazardous substances are produced. We want this test to be universally reproducible, at an affordable price, using meters easily obtained in local stores and performed by people without laboratory experience, to guide people and health professionals to obtain a simplified understanding of the dangers of the current and potential smoking devices.

We bought a Iqos Iluma One™ and Terea™ cigarettes from PMI. The operating temperature was measured with a thermodetector and K probe (BOSCH GIS 1000C Professional™). Measures were obtained first from the inside of the cigarette and then on the metal warming sheet alone. CO was looked for as a combustion marker, placing the device in a closed 16l box, without air exchange, together with a personal and environmental CO meter. (BreathCO™, Vitalograph). The emission of 2.5μm particulate matter (PM2.5) and the increase of total volatile organic compounds (tVOC) were evaluated with a commercial air quality sensor (Vindstyrka E2112™, Ikea of Sweden AB), and a manual syringe-type suction pump, which draws 200ml of fresh air 10 times per minute, through the HNB device and its cigarette. The thermodetector was tested by boiling water, achieving an accuracy of ±1°C. The CO detector was zeroing before starting the measurement. PM2.5 detector lacks user calibration. To avoid confounding factors, the presence of environmental contaminants was recorded during the test, and only changes were considered. When turning on the device, smoke was observed coming out of from the cigarette (Fig. 1A). It worked for about 6min and turned off automatically. Maximum temperature recorded was 284°C inside the cigarette and 300°C in the metal sheet alone, which, was seen in previous devices.9 CO was detected and increased from 0 to 43 PPM. Inside the smoking box, PM2.5 went from 2μg/m3 (ambient) to 887μg/m3 and tVOCs also increased. Under visual control, it was observed that the tobacco underwent pyrolysis (a form of organic matter thermochemical decomposition), its strands dried, darkened and became brittle, with a charred appearance (Fig. 1B-1 and 2). The filters became impregnated and acquired a brownish hue (Fig. 1B-3). Charring due to pyrolysis was observed in the tobacco plug in older devices too.10 The researcher smelled a characteristic odor and perceived nasal irritation while performing different tests, even though the smoke initially observed had disappeared. The temperature reached by the device caused pyrolysis, evidenced by the appearance of CO and the carbonization of the tobacco. This temperature is much higher than that necessary to cause protein glycation. Known as the Maillard reaction, it occurs between the amino groups and the sugars present in tobacco, forming harmful and pro-carcinogenic compounds. The problem that each type of tobacco can release different toxins can be solved by measuring very small particulate matter that could reach alveolar region.11 Olfactory perception can be correlated with the existence of a non-visible lateral current. It would not be surprising since it was previously described in other systems, supposedly smoke-free.6 Due to the pyrolytic changes observed and the presence of CO, it is evident that this device burns tobacco. Perhaps one of the most important strategies of the industry is to declare that this device does not generate smoke. Oxford Dictionary says about smoke is the gray, white or black gas that is produced by something burning (https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com). In Spanish language is similar, a “visible” mixture of gases produced by the combustion of a substance, generally composed of carbon, and which carries particles in suspension (https://www.rae.es). Well in this work, all these things were detected. Even non-visible carbon particles and other toxins are extremely dangerous. Low levels of contaminants could be enough to generate disease in users and in second-hand smokers. Tobacco does not show a safety threshold12,13 and respiratory and cardiovascular abnormalities could be related to HTP exposure.14,15 We could speculate that smokers who inhale IQOS™, even if they received less exposure, will suffer similar consequences to those who smoke a single CC per day and who have also reported serious damage to their health, such as an increased risk of cardiac disease by 74% and stroke by 30% in men and even worse in women, 119% and 46% respectively if confounding factors are considered.16 Future research should focus on cardiovascular, pulmonary, and systemic inflammatory events17 and focus on “hard-to-see smoke” and its possible equivalence to second- and even third-hand smoke. We need to know if devices with new Bluetooth connection capabilities with phone apps could share usage patterns, preferences, and other personal data with the manufacturer.

Our experimental approach has some limitations, so we do not intend to quantify values, only to demonstrate the presence of toxic compounds and the combustion phenomenon. The choice of instruments was based on low cost, wide commercial availability and ease of use.

PMI is carrying out an aggressive promotional campaign; which does not seem to be limited to getting smokers to switch to this device, but is trying to attract non-smokers and young people.18 IQOS™ and Its cigarettes are usually located near youth-oriented products in prominent and easily visible places. The packaging of their cigarettes has colors that are easily related to flavors and strength of tobacco. Retailers often describe IQOS as less harmful, smokeless and useful for quitting smoking. All of this is very worrying since an erroneous perception about the safety of the product is related to tobacco consumption.19

We believe that authorizing the use of reduced-exposure messages is a serious mistake, and that it inevitably leads to misconceptions about their security. It's worth asking whether we’re doing the nicotine addiction industry a big favor when we compare toxic levels between different forms of smoking knowing that any level of toxicity is a real risk, or when we use terms like aerosol, vape, stick, and others instead of smoke, smoking, smoking, or cigarette.

Denying that HNB burns tobacco is a fallacy and a clumsy attempt to minimize its health dangers. Banning advertising is a key point.

Author's contributionAFG, FHG, JS: bibliographic search & discussion, experimental design, selection and assembly of instruments, experimental execution.

AFG, XAR: photographic development, documentation & image selection.

AFG, NPR, XAR, PKA: first draft of the manuscript, first translation into English

AFG, CJR, CRC, JIDGO, JARM: commented on previous versions of the manuscript, correction manuscript structure and translation review.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was funded by none.

Conflict of interestsAF-G reports support for attending meetings from (alphabetical order) Adamed, Aflofarm, GlaxoSmithKline, Menarini, outside de submitted work. Membership in SEPAR and therefore no relationship with the tobacco industry. NP-R reports support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi, outside the submitted work. FH-G reports speaker and support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Gebro, outside the submitted work. JS reports speaker and consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Gebro, Astra, Chiesi, outside the submitted work. JAR-M reports grants and personal fees from Aflofarm, GSK, grants, personal fees and non-financial support from Pfizer, Novartis AG, Menarini, personal fees and non-financial support from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees and non-financial from Astra-Zeneca, Grants and personal fees from Gebro, personal fees from Laboratorios Rovi, outside the submitted work. JIG-O has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications for the following (alphabetical order): Aflofarm, AstraZeneca, Boehringer, Chiesi, Esteve, Faes, Gebro, Menarini, and Pfizer. CJR: Fees for studies, presentations and scientific advice with the pharmaceutical industry, Aflofarm, GebroPharma, Bial, Johnson&Jonhson, Chiesi, Menarini, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer. Membership in SEPAR and therefore no relationship with the tobacco industry. CRC: has received honoraria for lecturing, scientific advice, participation in clinical studies or writing for publications from J&J, Aflofarm, GSK, Menarini, Mundipharma, Novartis, Chiesi, Pfizer, and Teva. XAR reports speaker and support for attending meetings from Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi, PKA attending meetings from Chiesi. Authors declare to have no conflict of interest directly or indirectly related to the contents of the manuscript.